It is not surprising that, as was the case with many schools run by religious orders during the Spanish colonial period, the university’s founding Jesuits did not maintain a policy of coeducation when they took over the reins of the Escuela Municipal in 1859. Nearly a century would pass before the very notion of a female Atenean would become more than just an imaginary construct.

Women were finally allowed to lay claim to the Atenean identity when the institution’s graduate school turned coeducational in 1950. Eleven years later, the Ateneo Law School followed suit. By the summer of 1966, the administration had begun to permit women from exclusively female colleges in the country to cross-enroll in what was then known as the university’s College of Arts and Sciences (CAS).

Controversial beginnings

Although it is not an unusual sight to see female students in the Loyola Schools today, one can easily take for granted the fact that the very idea of a coeducational undergraduate school was a matter of much controversy when the administration began to consider such a policy seriously during the late 1960s. The all-male student population of the CAS did not hold unanimous views about the prospect of seeing female students around the campus.

The movement took a hit in 1968 when a resolution against the implementation of coeducation was passed by the undergraduate student government. This was due in part to the fact that the university senate, a precursor of today’s Sanggunian, had voted against such a policy. Nevertheless, that did not stop the more progressive students from bringing their goal into fruition in the long run.

A plebiscite conducted by the administration in 1970 yielded affirmation that the Ateneo should, at some point in the future, begin accepting female undergrads. However, the affirmation came with the condition that coeducation would not be implemented yet the following school year.

Two years later, the supporters of coeducation scored a landslide victory when, in another plebiscite, approximately 80% of the student population voted for the policy change. By then, the university senate had reversed its decision and had opened up to the possibility of a coeducational undergraduate school.

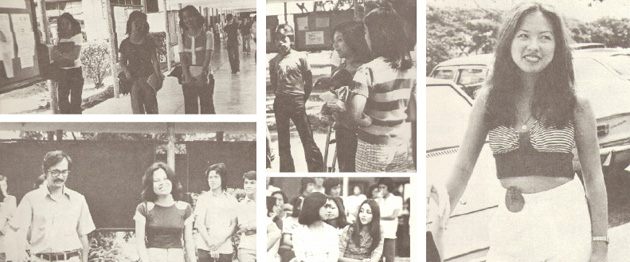

The CAS finally began accepting female students in 1973. In the four decades following that historic change, the Ateneo has served as home to a lot of notable female alumni who have made significant impact in their respective fields.

“Revolutionary”

“You have to remember that, [at that time], the concept of coeducation was nothing short of revolutionary. In fact, the very idea of a woman actually going to college and taking a course remotely serious or heavy-duty was pretty unheard of. This [sort of logic] was coming off a previous generation where women were expected to go to a conservatory of music, and that’s it—end of [their] life story,” explains Lisa Nakpil (AB Eco-H ’77) co-founder of The Ateneo Women and one of the first batch of female undergrads.

One would think that, having taken up basic education in an exclusive school for girls, Nakpil would have a difficult time adjusting to a college that had just turned coeducational. That was not the case. “I’d like to think that it was the male students and faculty who suffered more from the pains of adjustment. I think they would agree.”

Nakpil explains that the social dynamics on campus during her college days was, to a certain extent, quite different from that we know today. “Coeds were very much an oddity—sort of like a freak-show curiosity. And I often felt that my male classmates and teachers were astounded that we could even spell or do sums.”

“I was told that there was a general uprising among the male students when the number of their toilets was cut down to make room for ladies’ rooms. It was pretty laughable,” she recalls. “I do recall that the Jesuits in their usual thorough manner also kitted out a special ‘Ladies Lounge’ for the coeds—it looked like something out of the ladies lounges in Sunset Boulevard, with aggressively feminine floral curtains and settees.”

“In retrospect, I believe it was less of a concession and more of an attempt to corral us. You know, [to] keep us away from the ‘general population,’” she adds.

Nakpil says that there have been instances when she felt the sting of misogyny from male students. “Yes, we were treated ‘differently,’ and quite a few times, total strangers would come up to me at the cafeteria and say, ‘You do know you’re wasting a perfectly good slot in this school when you’re just going to wind up getting married? … I am told that the other coeds had to suffer all kinds of what would be today classed as harassment.”

If given the chance to once again go through college in an Ateneo of the 1970s, however, Nakpil would not hesitate to do so. “[Atenean men] are the last of the country’s gentlemen,” she says.

Empowered

Throughout her ten years of teaching in the university, Political Science Department Assistant Professor Ma. Lourdes Rallonza, PhD, whose research interests include women’s human rights and women’s movements, has observed changes with regard to the temperament of the female student populace. “[Recently], young women leaders have gotten in touch with me in order to help them out with forums on women’s rights, and to seek advice on creating an all-woman student organization. Previously, wala iyon (there were no such things).”

Nevertheless, she has encountered occasions where gender perceptions of students seem to be coming from a misogynistic point of view. “Usually, the most vivid reactions I get is when [my students] talk about women’s rights laws in the Philippines.”

A common example of such is when the concept of rape is discussed during her class. “When I get a progressive answer from a woman defining rape as… not necessarily having to be the penile penetration of the vagina, some of [my male students] snicker. They have a very narrow-minded view of rape and sexual assault,” Rallonza says in a mix of English and Filipino.

“That is where I see how penile-centered the minds of some men can be. And in that light, they are not actually open to other forms of violence, particularly when it comes to women,” she explains. “And this has actually been, throughout the years, the same reaction always with some of the men.”

Compounded issues

Although the status of women in the Ateneo has changed since the onset of coeducation, the same cannot be said for those outside the institution. When juxtaposed with her counterpart from down the hill, the Atenean woman has been living a more privileged life.

“Gender issues are never isolated from other issues. One of the basic points of intersection is gender and economic status. Atenean women are definitely better off. They don’t have to contend with double problems of poverty and gender. Gender issues get compounded when they intersect [with] poverty,” explains Philosophy Department Assistant Professor Jean Tan, PhD, who has taught courses on the philosophy of woman.

“Poor women contend with different sorts of issues, such as battery, violence against women, and not all of them are just purely gender questions. If you’re a poor woman who keeps getting beaten up and you have no resources, it would be much more difficult for you to leave your partner [compared to] if you are well-to-do,” she says. “[Poor women] don’t only have to deal with general poverty; they also have to deal with child bearing and childcare.”

Rallonza agrees. “When you talk about poverty, it has a feminized face.” Another comparable situation she points to is the marginalization of women who have been affected by the country’s armed conflicts.

“The conflicting parties have peace talks, but I do not see the integration of gender concerns in the talks,” she says. “I’ve been in the field, and I’ve spoken to women in conflict zones, and they themselves tell me that they want to wake up in the morning without having to deal with the fear of gunshots, encounters, and evacuations from happening.”

She adds that the constant state of alarm such difficult situations bring about—coupled with traditional household jobs delegated to women, such as having to care for the children and cooking food—has deprived these women from reaching their full potential. “This kind of life creates so much anguish and burden to these women that they are not actually able to be productive.”

Room for improvement

Tan says that there remains to be much room for improvement with regard to the development of women’s rights in the country. “There are still gender divisions in terms of what jobs are available or what careers women go through… [Society has] preconceptions about gender roles.

“Feminist demands are very often framed by patriarchal culture in terms of women wanting to have cake and eating it, too. For instance, if women want to develop careers, society would say, ‘Well if women do that, they will have to forego having children.’ Women are forced into a corner and can’t have both,” Tan says.

Women and the Church

According to Tan, one of the most explicit forms of patriarchal domination manifests itself in the form of what she believes to be the limited number of roles that women can play in the Catholic Church.

“The Church has to address gender issues… I personally don’t see any real reason why women cannot be part of the ordained ministry. It’s not even a very subtle form of subordination. Women can be the nuns who assist the priest, but they themselves can’t be priests. They can’t be pastoral leaders in a way that men can.”

Tan argues that dissonance exists between the magisterium’s doctrine and practice, most especially with regard to its teaching that all human beings are created in the image and likeness of God.

She says that religious injustice emerges from the Church’s seeming lack of hospitality towards the female sex. “This form of injustice is something that the Church in general does not recognize. It recognizes other forms of injustices like poverty, political corruption, discrimination in terms of race, but in terms of sexual discrimination, it’s a blind spot.”

“Rape culture”

Isabelle Biscocho, a junior political science major and the magistrate for audit of the Student Judicial Court, points to a certain rape culture as one of the most pressing issues faced by many young women in Philippine society today. “[Rape culture] is all about teaching women to dress properly or teaching them to cover up, instead of teaching other people not to rape,” she explains.

Biscocho cites, for example, the case of the students of the all-girls Saint Theresa’s College in Cebu who were not allowed to join the graduation rites of their school last summer, on the grounds that pictures of themselves wearing bikinis surfaced on Facebook. “Why did they make such a big deal about it? It’s just a simple bikini picture.”

Back to school

But even in the Ateneo, the attire of women also seems to be treated as quite a big deal.

It is in this regard that Tan thinks some of the university’s gender-related policies are reflective of a Philippine society that remains saturated with misogynistic prejudices.

She cites the dress code as a manifestation of these prejudices. “If you look at the examples [of the dress code], they are mostly restrictions on what women can’t wear… It’s a function of how women are shaped to present themselves.”

“It’s not just about what administrators think. You can see the rationale on why they implement [the dress code], but at the same time it’s so reflective that no one really thinks about the genders implications,” Tan says.

Tan believes that women have been caught in a bind because of the way society dictates how they should dress. “Patriarchal society tells us that women are the ones looked upon and the men are those who look. How does that translate into policies of dress code? Women get policed more than the men. It’s sexual politics that enters into the way we behave and how we dress—and we don’t think about that.”

Learning through experience

Although the condition of the Filipino woman has improved over the years, Rallonza argues that the general advances have amounted more to a slight step forward rather than a giant leap.

In this light, she believes that societal education on gender issues must be pursued—though not just through the conventional methodology of classroom-based learning, but through something more founded on experience and action. “Education should be supported by application,” she says. “Learning should have a soul, because if learning has a soul, you would… not just theorize as a matter of habit.”

Her argument, in its core, is for a gender equality that does not just remain on the level of theoretical discourse, but rather, also manifests concretely in active practice.

HEAR ME ROAR. Long after the university began accepting female students in 1973, the struggle for equality continues. Photos From Aegis ’75, Courtesy of the University Archives.

There She Goes

In what was once an all-male university, women now outnumber men in the undergraduate school.