Burgis, conyo, and sheltered—such labels are easily affixed to the stereotype of a student from the Ateneo. It has become a social construct within the ambit of Philippine culture to define Manila’s top universities as those which cater to an exclusive group of elite individuals.

Despite its reputation as an institution of privilege, however, it is quite ironic that the academia is recognized under Philippine law to be non-profit. Hence, balancing the university’s budget has always been an important though presumably challenging matter for the administration.

It is for this reason that the Ateneo undergoes a thorough process that determines both how much money is to be spent the following year and at what rate the tuition and other miscellaneous fees are to be increased. The revenue collected from enrollees constitutes the bulk of the university’s yearly income.

Vice President for the Loyola Schools John Paul Vergara explains that the procedure is a year-long process that begins when the Ateneo’s different offices and departments submit their budget requests to the administration.

These proposals are then processed by the Loyola Schools Budget Committee (LSBC). “After several meetings, [the budget] gets consolidated around December, and then presented to many sectors [of the Loyola Schools community]. It is the LSBC that has it approved in the university level.” However, Vergara is quick to point out that the university maintains a cap in setting the rate of increase.

With a pedagogical tradition to uphold, endeavors to fund, and an upkeep of about one hundred hectares of land to manage, it is indeed not surprising that the Ateneo’s tuition constantly rank among the highest in the country.

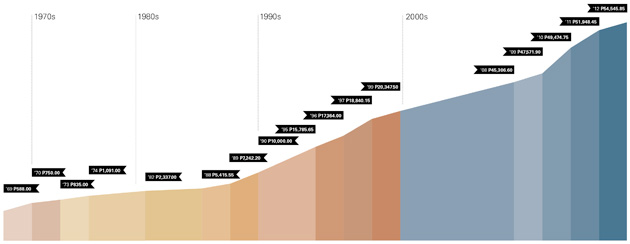

Tuition through the years

Never has there been a period in the university’s history when the tuition would decrease from that of the previous year. It has become a perennial event in the campus for the administration to announce an increase in the fee. The highest rate of tuition increase in the university’s contemporary narrative stands at 20%. This sharp spike happened twice, in 1986 and 1991.

In 1969, the university’s tuition stood at P588. From that point, it took less than five decades for it to breach P50,000 in 2011. The basic tuition currently stands at P54,545.85 per semester.

Despite its regular, annual occurrence, however, it is important to take note that some members of the Loyola Schools community have not become normalized to the yearly increase in tuition.

Financial strain

Apart from having to deal with the rigorous academic workload of a student’s life, a number of current Ateneans have also found it quite difficult to keep up with what they argue to be the strain from the university’s financial demands. What makes things much worse for them is the fact that their families bear the brunt of such a burden.

Take the case of Daisy*, a third year college student. Her parents have found it very difficult to find money to pay for her tuition, given the fact that she and her siblings are all being educated under the banner of the university. “[My parents] borrow money to pay for our tuition. My dad also needs to earn extra income aside from his work, so he does [side jobs].”

Such a scenario echoes that of junior student Theodore*. “Besides the usual savings and lessening of miscellaneous expenses, there would be a lot of instances when there had been the need to pawn items from our home such as the sound system we use, the family car, laptops, and jewelry.”

Neither could fate be so kind to Walt*, who is currently in his second year of college. “I have other siblings who are also studying, and the insurance company that [was] supposed to pay 50% of my tuition fee informed [my family] that they won’t be able to pay for it.”

Failed alternatives

In 1986, clamor for the reform of the tuition fee system arose in the university. Proponents of change argued for the enforcement of a Socialized Tuition Fee (STF). Such a system entailed that the amount of money that a student had to pay for tuition was to be based on the annual income of his or her family.

The movement gained ground, but did not bring about total consensus from the members of what was then known as the College of Arts and Sciences (CAS). Those against it argued that it propagated the discourse of a “Robin Hood mentality,” which was taken to mean as the stealing from the rich to give to the poor.

After a series of debates and studies, the STF did not push through. Nevertheless, another movement for tuition reform was revitalized on campus in 1988.

The STF took on a brand new identity as the Full Cost of Education system (FCOE). This scheme rested on the argument that all Ateneans during that period were at least partially scholars, given the fact that they were not actually paying for the full cost of education. Substantial expenses for research, service awards for the faculty and staff, and the construction of what was then the new annex of the Rizal Library were being paid for by the university’s donors.

Implementing the FCOE meant that students would have had to pay for the full cost of an Atenean education. This included the previously mentioned expenses as well as other miscellaneous fees. Such a scheme would have necessitated an increase in the tuition rate by as much as 40%.

The plan, though, was that students were to be divided into two brackets. At one end were those who could afford to pay the full cost of education. In the other side of the fence were those who did not have the means to do so—such a group would have been exempted from paying the extra fees. Concerns were raised that implementing the FCOE would drastically decrease the student population of the CAS, thus defeating the system’s purpose of increasing the university’s finances. The entire debate on the matter lasted for about four years until it died down due to waning interest.

Aside from the STF and the FCOE, the administration of that era had also explored other systems of funding. They had explored the possibility of using the frontage of the university estate for commercial use. Another suggestion involved the transfer of the Ateneo Law School to the Loyola Heights campus, so that its buildings in Makati would be available for renting out.

What seemed as a more reasonable idea was to give students a chance to loan their college education from the university and have them pay it back after graduating from college. Such a plan is similar to the loan schemes put in place by many universities around the world today. Nevertheless, such alternatives failed to prosper.

The current tuition scheme is quite similar to that of the FCOE. Data from the Office of the Vice President for the Loyola Schools shows that 78% of the tuition gathered from regular students for SY 2012-2013 is to be allocated to salaries for the faculty and staff, as well as other benefits that include grants, research work, financial assistance, and awards.

Another 16% of what is paid goes to student scholarships and financial aid. The remaining 6% is spent on the other operating costs and capital expenditures of the Loyola Schools. What sets this scheme apart from the FCOE is the fact that the brackets are not divided according to a family’s annual income. What is implemented instead is the separation of the student populace based on merit—one is either a regular student or a scholar.

Consistent trend

Given the fact that the tuition fee has increased by an average rate of 4.75% over the past four years, there is enough basis to project how much tuition would turn out in the future. If the yearly rate of increase remains consistent, it is estimated that the tuition would surpass the P60,000 mark by 2015.

On the other hand, by 2022—10 years from now—it is likely that regular students would have to pay an estimated P86,756.50 for the tuition alone.

After all, a tuition hike has taken place without fail every year, so much so that it seems to have become part and parcel of Ateneo life. There is no reason to think that it would be any different in the coming years.

*Name has been withheld upon request.

With reports from Tanya F. Rosales

A history of numbers

In comparison

| Basic Tuition Fee | Crude Oil |

| 1969 – P588.00 | 1969 – $3.30 |

| 2012 – P54,545.85 | 2012 – $87.48 |

Research by Paolo M. Taruc