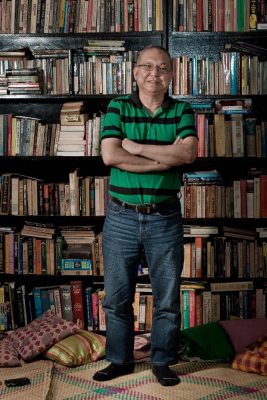

Shall we sit?” asks Ricky Lee, removing his black leather shoes.

Being invited into someone’s home is one thing, but sitting with a literary legend in the confines of his personal library is another. The authenticity of Lee’s warm smile was the most welcoming sight among the many things that spelled out “welcome”—the scent of old novels, the hand-woven mat we were resting on and the cozy throw pillows around us.

It’s no secret that Filipino writers receive little appreciation from their countrymen. Even for someone like Lee, who has written everything from short stories to screenplays, something as simple as being recognized in an average Atenean’s Filipino 12 class is a challenge. “Half of the time, people call me ‘direk’ because the writer has no identity,” he says in a mix of English and Filipino, referencing the film industry in which he has also worked.

After a morning spent walking in what seemed to be a trophy exhibit, it’s safe to say that this startlingly humble veteran writer is among the finest our country has ever seen.

“I don’t think I’m the best, The moment when you start to think you’re the best, you’re dead as a writer.” – Ricky Lee

Beyond the recognition

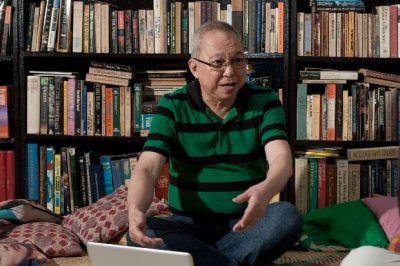

“I don’t think I’m the best,” he blatantly points out. For a man who holds over 25 years’ worth of bragging rights under his belt and more than 50 trophies to prove it, the certainty in his voice caught me by surprise. “The moment when you start to think you’re the best,” he says, “you’re dead as a writer.”

Perhaps it is this mentality that got Ricky Lee to where he is today, working with famed Filipino directors like Joel Lamangan and Ishmael Bernal, all while pushing his creativity to the limit through the novel—an avenue he only began exploring recently. That, along with his indomitable zeal for storytelling, has attracted film festivals and award-giving bodies alike, catapulting him into the literary limelight.

As impressive as the Cannes Film Festival and Palanca Awards sound, though, Lee’s accomplishments go beyond titles. “Ricky Lee’s works maintained and deepened my interest in literature. And so now that I’m a teacher, my belief in him carries over when I assign my students to read his creations,” Filipino professor Pam Cruz says in the vernacular.

It’s quite fascinating how someone who hasn’t let trophies change his integrity as a writer has not only changed the landscape of the Philippine film industry and Philippine literature, but has also given it a new dimension for students to grow in.

Challenge accepted

Somewhere along our conversation, I couldn’t help but wonder whether it has ever occurred to him to write about his own rich history. His struggles as a runaway orphan in the face of poverty and as an incarcerated fugitive during the Martial Law years must have provided him with a wealth of inspiration to draw from. While it made for an interesting assumption, I was wrong.

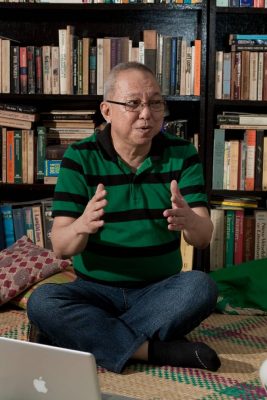

The closest that Lee gets to being inspired is when he listens to music. “Each of my films, each of my books was made with one or two CDs on repeat,” he says in a mix of English and Filipino. For his first novel, Para Kay B, it was Coldplay; for the 2004 film So Happy Together, it was The Killers. As for the recent Si Amapola sa 65 na Kabanata, it was the Kings of Leon.

Other than his far-flung dreams of being a rock star, Lee deems inspiration unnecessary. “I don’t need to be inspired to write; the inspiration is just an extra push,” Lee says without the slightest hint of hesitation. The way he sees it, there is no need for that extra push if one already knows what he’s meant to do—in his case, winning his first national literary award (and getting paid for it) for a short story in high school made his purpose apparent. “It’s as if there’s nothing else I know how to do,” he admits, chuckling to himself.

Lee finds comfort and security in his passion despite the knowledge that being a Filipino writer who writes in the native tongue is no easy task. “It’s difficult to be a writer in the Philippines, and yet why do I write?” he posits. “Maybe precisely because it’s difficult to be a writer.”

Holding his own

Tracing his roots back to his college years in the University of the Philippines where he became an activist during the uproar of the Martial Law era, Lee has made it a point to hold firm to his convictions. A former English major, Lee initially wrote primarily in English. These days, however, he chooses to write only in Filipino as a testament of his love for the country.

No exception to this oath is Si Amapola sa 65 na Kabanata, Lee’s second full-length novel, following the success of Para Kay B. Written in humorous and thought-provoking Filipino, it tells the complex story of a gay impersonator-turned-manananggal (a Filipino mythical monster that can detach its upper body from its legs and fly) prophesied to save the Philippines.

Lee jokes about the seeming contradictions of being a “Chinese Bikolano who took up AB English and writes in Tagalog.” In a way, Amapola’s tagline seems fitting for Lee himself: “Lahat tayo hati, ‘di nga lang nakakalipad ang iba. [We’re all split, but not all of us can fly]”—for all the different parts that make up Lee, he manages to soar at his craft.

When asked why Amapola took three years to finish, Lee explains that making the socio-political threads run through the story smoothly was key to producing a good read for students, and that setting the novel in the 2010 elections along the streets of Morato required a vast amount of research. “I did a lot of work so that the audience would not have to,” he says.

Amapola was launched last November 27 in SM North EDSA, with local actresses (and Lee’s good friends) Ai-Ai de las Alas and Eugene Domingo as the hosts and a star-studded entourage as guest readers of excerpts from the novel. As can be said for Lee’s other works, his hard work paid off.

I was halfway out his front door when Ricky Lee offered to give me a poster and some stickers of his new novel. As if to reassure me of his down-to-earth personality, he signs the gifts with a phrase that couldn’t have been more fittingly said by another person: “Keep your feet on the ground when you fly.”

With reports from Apa M. Agbayani

- Photo by Abram Barrameda

- Photo by Abram Barrameda

- Photo by Abram Barrameda

- Photo by Abram Barrameda

- Photo by Abram Barrameda

- Photo by Abram Barrameda

- Photo by Abram Barrameda

- Photo by Tim Arafiles

- Photo by Tim Arafiles

- Photo by Tim Arafiles

- Photo by Tim Arafiles

- Photo by Tim Arafiles

- Photo by Tim Arafiles

- Photo by Tim Arafiles

- Photo by Tim Arafiles

- Photo by Tim Arafiles

- Photo by Tim Arafiles

- Photo by Tim Arafiles