Three years after multiple suicides rocked the Ateneo, the school has created a system that will stand by the side of those who need most help. Photo by Jessica L. Roasa

It was the year 2008. The university was one year away from celebrating its sesquicentennial, and the entire community was celebrating the school’s victory in capturing the first of what would be four straight championships in UAAP Basketball.

The basketball win over La Salle was a bittersweet ending to a semester that left many in the community harboring feelings of loss and grief. Pomp and circumstance that accompanied the celebrations sharply contrasted with the distress and pain many Ateneans coped with for months. In that semester alone, three members of the community tragically took away their own lives.

Time seems to have healed the wounds of this sad episode, yet three bonfires later, the heartbreaking events of that semester still loom large over Loyola. They have left a lasting mark on the school, especially in the reforms that the Ateneo has introduced since then.

Suicidal thoughts

“To have brief passing thoughts [about suicide] is normal. That happens… but to ruminate on them is not [normal],” explains Loyola Schools Guidance Office (LSGO) psychiatrist Patrick Lorenzo. Lorenzo usually handles cases related to suicide for the LSGO.

According to Lorenzo, a person at risk of suicide tends to have a certain set of beliefs that center on helplessness, hopelessness and worthlessness. “Most [Ateneans] at risk of suicide tend to echo these beliefs,” he says. “They go by the discourse that they can’t do anything right, and that there is no love and support. That’s helplessness.”

Speaking more specifically, he says, “[Ateneans at risk of suicide] feel that they are not in control of their [stressful] situations. They think that they can’t save their grades anymore, or that there is no possibility of mending a fight with a loved one.” He explains that these students believe that “there is nothing more to look forward to in life”—a result of their feelings of hopelessness.

Based on his experiences with students at risk, Lorenzo especially mentions family problems as being significant triggers for suicidal thoughts. Reaffirming the fact that the institution of the family is foundational in Philippine society, he says that “… a dysfunctional family often leads to immense stress for many Ateneans.”

A change in policies

During the years leading up to the first semester of 2008, the Ateneo’s systems in handling suicide cases were still quite ambiguous. The policies in place today, however, are quite different compared to the ones implemented before.

“It was practically just [the duty of LSGO] in the past”, says Lorenzo. “Not everybody was aware of [suicide prevention].”

Assistant to the Associate Dean for Student Affairs (ADSA) for Services, Michael Mallillin, attests to Lorenzo’s statements. “In the past, most cases were just referred to LSGO.”

While the community has arguably not yet fully recovered from the tragic events of that eventful semester, what should be taken note of is the fact that the university has learned a lot since then.

Dozens of changes and reforms have been instituted by the Ateneo, in such a way that suicide prevention has now become systematized and integrated into the different administrative arms of the university. And so far, the changes seem to be doing well.

Indeed, if the months following the suicides are to be any indication, it seems that the new systems have been working quite effectively. No suicide-related deaths have occurred among members of the Ateneo community ever since the new policies had been instituted.

“There are now systems in place that [have] improved our detection of students who are prone of [risky] behavior,” explains Mallillin. “[For example], there are tests given for freshmen and upperclassmen.”

He also mentions greater efficiency in the way the school handles emergency situations. “Another improvement is the coordination of offices. If the possibility of a case occurs, there is a quicker line of communication between them.”

Concrete steps

ADSA has a significant role in the suicide prevention program, and it is a specifically crucial role because as Mallillin explains, “The first office that students would normally contact for an emergency is usually the ADSA.”

We are the only office that has a hotline, and all the students know it because it’s at the back of their IDs,” he says.

Something more concrete comes in the form of the Crisis Intervention Team (CIT). Formed in the beginning of SY 2009-2010, the CIT was mobilized as an apparatus meant to serve as a support system for students who have become too depressed to the point of entertaining suicidal thoughts.

In line with the university’s new approach of integrating the whole community, the CIT structure emphasizes the role of the different administrative offices of the university, such as LSGO, ADSA, the Office of the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, and to a certain extent, even the campus security and maintenance services. Faculty members are also tapped to assist in the effort, such as by referring students who are showing signs of unusual behavior to the LSGO.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the CIT is its emphasis on speed. “Sometimes, it is only a matter of minutes that separate a student from life and death,” Mallillin says. “If we get a call from someone who is at the [brink] of committing suicide, we make it a point to locate them [and] go to them, even if the student may be outside of the campus.”

He is also quick to point out that all cases related to suicide are handled by the school with utmost importance, no matter how trivial or how light the degree of a student’s suicidal thoughts might be. He also says that such cases are not treated as one-time episodes. “Treatment does not end after counseling. We follow up with the students [at risk] from time to time,” Mallillin says.

Obligations of the community

There is hardly any surprise in the fact that the possibility of suicide has crossed the minds of a number of Ateneans once or twice, given teenagers’ and young adults’ higher rates of suicide in general. It is therefore reassuring to note that the university has exerted effort to structuralize suicide prevention in campus, especially in comparison to other universities. This is a particularly important effort in a university that has a regrettable past in the matter.

“To the best of my knowledge, the Ateneo is the only university in the entire country with a solid suicide prevention program,” Lorenzo says. “Other schools have consulted me for advice in establishing or mobilizing theirs.”

He affirms that much has improved in the Ateneo’s system for suicide prevention, ever since the events of 2008. However, he believes that there are new goals that the community must now work towards. “The goal this time around is to empower the Ateneo community. We want everyone to be capable of saving lives and of handling [suicide] scenarios,” he says. “We want people to be aware of simple guidelines in dealing with depression and grief.”

This is because Lorenzo believes that constant vigilance is the key to suicide prevention—and not just on the part of professional psychologists or psychiatrists like him. He says that the friends and families of students at risk also have the power to save the lives of their loved ones. In this regard, he emphasizes the value of communication between home and school, or between an individual’s friends and the proper authorities.

“Once you tell us your concern, the whole [suicide prevention] network will be notified immediately,” he says, underscoring the need for members of the community to contact LSGO or ADSA as soon as they notice possible signs of suicidal thoughts in their friends.

But he does not dismiss the value of direct intervention. In fact, he believes that that, sometimes, it might even be completely necessary.

“If you have a friend on the verge of suicide, don’t hesitate to tie them down just so they won’t be able to kill themselves,” he says. “Your very [physical] presence will give them second thoughts of killing themselves.”

It is clear, though, that the whole business of suicide prevention involves the cooperation of all members of the community. Illustrating that the work he does must not be exclusive to his profession, Lorenzo says, “We must keep reminding ourselves that we are all obliged to save lives.

Suicide statistics

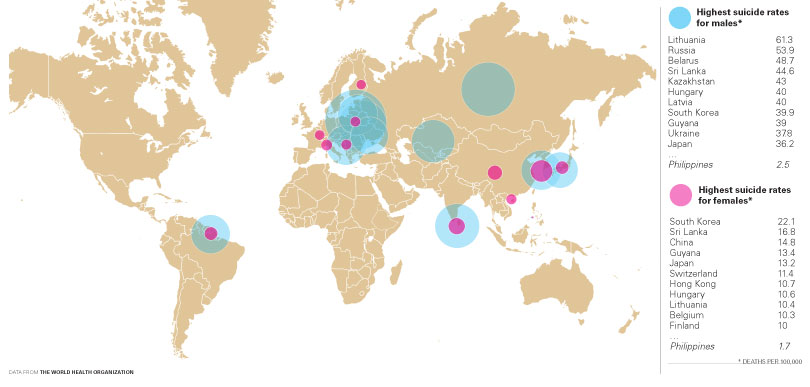

The Philippines maintains a relatively low suicide rate compared to other countries.

Data from the World Health Organization