Eleven years. That’s how long the Ateneo’s formal Fine Arts program has been in existence. At first glance, a very young age—until you realize that what happened eleven years ago was merely the institutionalization of a culture that has flourished in the Ateneo since the very beginning.

The arts and humanities have always been a defining aspect of the school—even way back when the Ateneo was still in Intramuros, there was heavy emphasis on the bellas artes. School theatre flourished, and pianos were a ubiquitous sight in the corridors. Even the young Rizal played his part: as a young Atenean, he crafted award-winning plays and sculpted his now famous statuette of the Sacred Heart.

Such humanistic endeavors have flourished in the school ever since. Numerous literary periodicals have cropped up in campus throughout the decades, such as Heights. In the ‘80s, the Ateneo had a Festival of the Arts, an annual celebration of culture in the school.

Fast-forward to the present, and the Atenean culturati is still going strong. The Ateneo Art Gallery has been setting up magnificent exhibits, and numerous Ateneans still make it to the annual list of Palanca awardees.

Still, not everything is perfect for the artists of Loyola. In fact, from concerns as small as stereotypes to issues as significant as the lack of school support, artists in the Ateneo are battling it out in multiple fronts—all for art’s sake.

Mise en scène

Just before the Christmas break, Ateneans might have noticed how the old Rizal Library suddenly looked so bare. After months of being photographed, artist Leeroy New’s massive art installation, entitled “Balete,” was finally stripped off the library.

“Balete” is just one of the many artistic works prominently featured in campus from time to time. Currently, for example, the Ateneo Art Gallery has an exhibit showcasing Philippine modern art from the post-war period, as part of its 50th anniversary celebration.

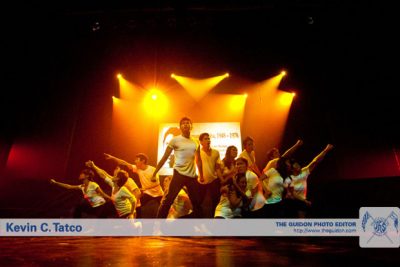

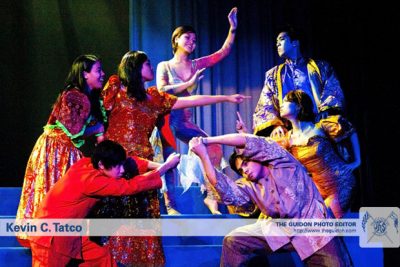

Artistic endeavors by students can also be seen everywhere in campus. Three student theatre orgs regularly stage plays, while the Company of Ateneo Dancers recently took top plums in the Skechers Street Dance Competition. Other humanities-oriented student groups, such as Blue Symphony and WriterSkill, are gaining more visibility in campus.

Meanwhile, the School of Humanities (SOH) continues to rank high in evaluative surveys. In the QS World University Rankings of 2010, Ateneo belonged to the world’s top 200 universities in the field of arts and humanities.

Loose change for a school’s soul

Still, despite SOH’s great successes, some tough challenges remain. A pressing concern for humanities students that seems partly due to SOH’s small population is the school’s representation woes. Much has been written about SOH students’ frequent non-participation in the Sanggunian elections—something that has often resulted in SOH’s lack of elected representatives.

However, SOH’s problems with representation extend beyond the individual level. Discounting performing arts organizations, the humanities are underrepresented in the Council of Organizations of the Ateneo (COA), the official body in charge of overseeing Ateneo orgs. Moreover, most SOH orgs are unaccredited, further limiting SOH student’s channels for dialogue with the rest of the school.

APART Visual Arts Collective founder Genevieve Go (BS CTM ‘10), for example, says that the visual arts scene in the Ateneo has very little official support, and therefore has very limited means for creative output. While being a School of Management alumna, she founded APART to cater to students not pursuing Fine Arts degrees.

“As dramatic as it sounds, artists continue to struggle to get the same rights and funding as the rest of the programs in school,” she says. “[It is] surprising to me because the Ateneo is ripe with highly creative individuals and groups whose voices are not being listened to.”

One difficulty that the four-year-old APART faced was accreditation. With no org room, no funds and no school endorsement, getting sponsors for projects and establishing their credibility proved to be a difficult task.

According to Go, APART did become involved in several school-supported projects, but she describes the support as “inconsistent.”

“[SOH had us come over] in Arete [SOH Week] and the SOH Freshmen’s Night during the [Freshmen’s Orientation Seminar],” she says. However, she says that there was no support in terms of finances or helping with the accreditation application. “We’ve pretty much had to do it on our own.”

Go partly blames these difficulties on the accreditation system mandated by COA. She says that the system only works “for the orgs that it makes sense to.”

“[The system] focuses too much on numbers and data that SOH orgs are not focused on,” she says. “COA fails to take into consideration that a system that is numbers-oriented may not be universally applicable to all orgs.”

Despite these challenges, humanities orgs have still been getting by. The Ateneo Literary Society, for example, holds regular book sales and reading sessions during SOH Week. APART has also staged several art workshops and exhibits, although several of these required admission fees.

Quiet impact

The difficulties faced by humanities orgs seem to stem from characteristics inherent in SOH itself. Given SOH’s extremely small population (around 10% of the student body), SOH orgs naturally have much fewer members than other orgs.

For SOH Dean Maria Luz Vilches, however, the numbers remain just that—numbers. She says that despite its small population, SOH influences the entire student body.

“Forty-eight units of the core curriculum is SOH,” she says, referring to the core classes that all Ateneans have to take. “All Ateneans are SOH students. In that way, it’s a quiet impact on students—but it is there.”

She adds that the quality of students in SOH makes up for the small population.

“We’re not sad that there are only very few students,” she says. “We have very few—but very good—students… they’re passionate in their work.”

Perceptions and their price

Nevertheless, there’s no question that further promotion of the humanities is a necessary action. Such will be helpful in efforts such as making the case for the accreditation of SOH orgs.

However, such promotions will pose a huge challenge, partly due to the way SOH has been stereotyped and labelled. Tricia Gosingtian (BFA ID ‘10), a Loyola Schools Awards for the Arts awardee for her work in photography, says that while the school is promoted as a place for artists, the label can be intimidating.

“I’ve had blockmates shifting out of [Information Design] partly because they thought they weren’t artsy enough for it,” she says.

Go, meanwhile, acknowledges that the humanities as a field is “very vague and unfocused.”

Vilches blames this characteristic of the humanities for the difficulties of promoting it, saying that the field deals with abstract things.

“Promoting the humanities is very different from promoting [science] and business,” the dean says. “What will you say about the humanities? [Will you] say that you come to the Ateneo to be formed? They’re all abstract things.”

To work around this challenge, SOH has been inviting successful alumni to give career talks and help promote the school during recruitment talks and open houses.

Rich tradition

For both Go and Gosingtian though, improvements to the humanities course curricula should be a primary consideration. Go thinks that the Ateneo program is still “young and half-baked” compared to equivalent degrees in other universities.

“[SOH] should ask [itself], ‘What will make a person go to the Ateneo instead of La Salle, UP, or UST?’” Gosingtian suggests.

However, obstacles to carrying out such reforms in SOH remain—funding, for one. Vilches explains that most corporations choose to sponsor projects in academic fields other than the humanities, because doing so would make the sponsored project more concrete.

On its own, however, the school already has a scholarship fund of around P5 million reserved for promising students inclined towards the humanities. Vilches believes that there is no lack of interest in the arts, only current or possible future financial concerns for those who do decide to take up SOH courses.

Despite all these challenges, Vilches maintains that the Ateneo’s rich tradition in the humanities is still going strong.

“The humanities have always been here,” she says. “There can be no Ateneo education without the humanities.”

With reports from Katerina D. Francisco and Luther B. Aquino

Minority Report

The School of Humanities has the smallest population among the four Loyola Schools. Its students usually comprise merely a tenth of every incoming freshman batch.

2005-2006 – 10.76% of student population

2006-2007 – 12.09% of student population

2007-2008 – 11.81% of student population

2009-2010 – 10.13% of student population