As the Bugsuk delegation from Palawan fights for their ancestral land here in Manila, they stress the importance of community and nature in the face of development.

IN BUGSUK, Palawan, the harmony of everyday life is disrupted by the call for “development.”

In the span of 50 years, Sitio Mariahangin’s pristine white sand beaches and crystalline waters have become prime real estate for developers and businesses. Drawn by the area’s natural beauty, corporations have relentlessly pursued the land for their projects, encroaching on the lives of local residents.

In spite of these attempts, Mariahangin residents remain steadfast in their right to reclaim their land and protect it from corporate interests.

Paradise lost

Mariahangin, situated in Bugsuk, has always been bountiful. One of the residents’ main harvests from the sea is agar-agar, the local term for seaweed. While exported raw from the island, agar-agar is versatile and can be used to make gelatin and furniture, thus making it one of the residents’ most sustainable sources of income.

Mel Bundac, who lived in Mariahangin from 1969 to 1974, describes the island as “sagana” (plentiful). With plenty of seafood and native crops to harvest, part of their daily meals comes freely from the sea and land. In turn, the island’s natural generosity is inherited by its residents.

“‘Yung isda, kapag maraming huli iyan, ‘pag nadaanan mo, bibigyan ka. Galit pa sila kapag hindi mo tatanggapin yung binibigay. Lobsters, isda, kahit ano,” Bundac recalls. (When you pass by someone with a big catch, they will offer some of it to you. They’ll even get mad if you don’t accept. Lobsters, fish, whatever they have.)

This sense of community rings true even at present. Jomly Callon, President of Samahan ng mga Katutubo at Maliliit na Mangingisda sa Dulong Timog Palawan (Sambilog), shares that the leaders of Mariahangin have their own form of bayanihan. For them, any individual problem becomes the concern of the entire community.

While such is the simplicity of life in Mariahangin, these peaceful routines were disrupted on June 29 when armed men came to the island and pointed guns at the residents. Angelica Nasiron, one of the residents who witnessed the attack, recalled that the incident started with a speedboat, which the island’s children spotted. Alerted by its presence, the children ran to the sitio to call the adults.

When the adults came to shore, a second speedboat came, and armed men fired shots at two children, one of whom remained unscathed. With the shots continuing to ring out, the residents became increasingly fearful. “Wala kaming dala kundi cellphone at mga bunganga namin na panglaban sa mga armadong kalalakihan,” she recounted. (We had nothing but our phones and tongues to fight the gunmen with.)

Nasiron explained that when the residents called their local government and multiple police stations for help, they were ignored. Out of options, they reached out to the Palawan office of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR).

The Balabac police, who had initially refused to assist, claimed they had no boats to reach Mariahangin. It was only after the intervention of the Palawan CHR that they finally responded. However, by the time they arrived, the gunmen had already changed clothes and escaped on the speedboats.

Bridges burned

Since then, the armed men have made repeated visits to Mariahangin, patrolling the sea in a way that feels like surveillance for the residents. They have imposed restrictions on the community’s own shoreline and have even seized locals’ catches by force.

Though the arrival of the armed men was sudden, the struggle for ownership of Mariahangin has long stretched on for decades. Notably, Jewelmer Corporation has established pearl farms in the area, posing a challenge to the livelihoods of fisherfolk.

Likewise, San Miguel Corporation’s (SMC) plans for an ecotourism project across over half of Mariahangin’s 10,821 hectares of land have already been set into motion. The project was done despite the island’s original deed, which states that ownership belongs to Hatib Isa, an ancestor of Callon.

In June 2023, SMC employees arrived under the pretext of conducting the corporation’s Malasakit Program. However, instead of meaningful dialogue, Nasiron says that families were offered money to demolish their own houses and leave. Families not native to the island were offered Php 100,000, while those who have lived there for generations were offered Php 300,000.

The pursuit of the Mariahangin’s land remains relentless, with native families receiving increased monetary offers for their homes. When Bugsuk residents were forced out of the island during Martial Law, Callon recounts his grandfather saying, “Bago niyo kami paalisin sa Mariahangin, biyakin niyo muna ulo ko (Before you make us leave Mariahangin, you’d have to crack my skull first).”

Callon maintains that his grandfather is the reason the tribes were able to remain on the island. However, their ancestral and legal rights to the land have not prevented others from trying to drive them out.

The tribes’ limited resources are no match for SMC’s financial power, and residents feel that government agencies, including the National Commission on Indigenous People and the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR), are on the side of the private sector.

Romillano “Omil” Calo, Chairperson of Sambilog, shares that the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Environmental Management Bureau has already awarded SMC an environmental compliance certificate for their ecotourism project. This means that despite not having ownership of any part of the land, SMC will now be allowed to proceed to the next part of project planning.

For the residents, losing out on the land also means losing out on their sea-dependent livelihood. The farming of agar-agar alone is already a job that can sustain generations. “‘Yung pera na in-offer [ng SMC] may hangganan, pero yung hanapbuhay namin, habang-buhay.” Nasiron explains. (The money SMC offered will eventually run out, but our livelihoods are forever.)

Now, the current situation is not only forcing residents off the island and threatening their livelihoods but is also ruining the community’s close-knit ties. SMC’s monetary offers to Mariahangin families have had varying degrees of success. Some families have taken the money and left, while others have refused in an effort to assert their ownership of the land.

Nasiron shares that this tactic has turned families against each other, eroding the island’s well-established sense of community. Apart from losing the community cohesion, the dispersal of residents would mean diminishing the significance of tribal cultural practices over time.

Notably, Nasiron also emphasizes that the island is the final resting place of the tribe’s ancestors. For her and those who have decided to stay, no amount of money will make them leave their departed family members behind.

“Kahit ano pang gawin nilang panghaha-harass sa amin, hindi kami aalis diyan, matalo o manalo man kami sa laban namin; hindi kami aalis. ‘Yan ang pangako ko sa mga libingan na iniwan namin,” Tarhata Pelayo, one of the tribe elders states.

(We will fight for our rights no matter how relentless our harassers are, whether or not we win. We will not leave. This is my promise to the graves we left behind.)

Matira ang matibay

Although the conflict has spanned decades, the rapid escalation that happened last June has led the delegation of Mariahangin’s residents to widen their network in the span of four months. Since September this year, they have been speaking in universities, appearing on radio shows, participating in protests, and engaging with organizations willing to amplify their voices.

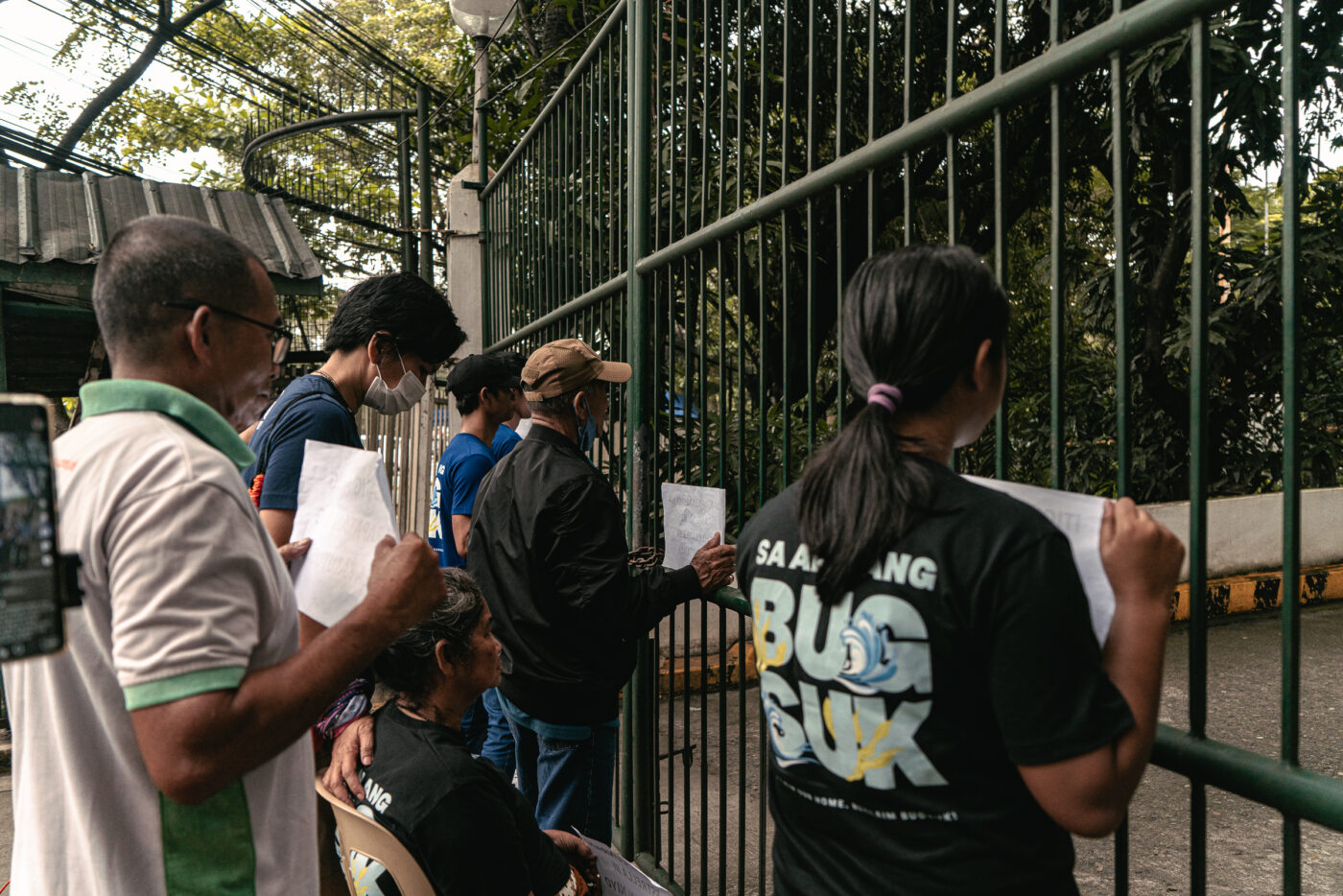

From December 2 to 10, the delegation camped outside of the DAR office in Quezon City as part of their nine days of prayer and fasting, waiting to hear from DAR Secretary Conrado Estrella III. The protest culminated yesterday with a mass, where they were joined by other religious communities.

Although Secretary Estrella III did not face the delegation, the delegation from Bugsuk remain hopeful that their movement would be fruitful, having already garnered support from students and religious groups and gained the attention of SMC.

On December 13, 2024 they will put a pause on their engagements to fly back to Palawan and spend Christmas with their families, but come January 5, 2025, the delegation will return to Metro Manila to continue their fight.Despite the uphill battle they face, Callon and the rest of the delegation lean on prayer and solidarity to keep them afloat. For now, they continue to hold on to the mantra, “Matira ang matibay” (Only the strong will remain).