Trigger warning: This article contains mentions of death.

THE WEIGHT of grief lingers long after losing a loved one. Unlike other stories shared on campus, those of loss and bereavement are often discussed in hushed conversations due to their sensitivity.

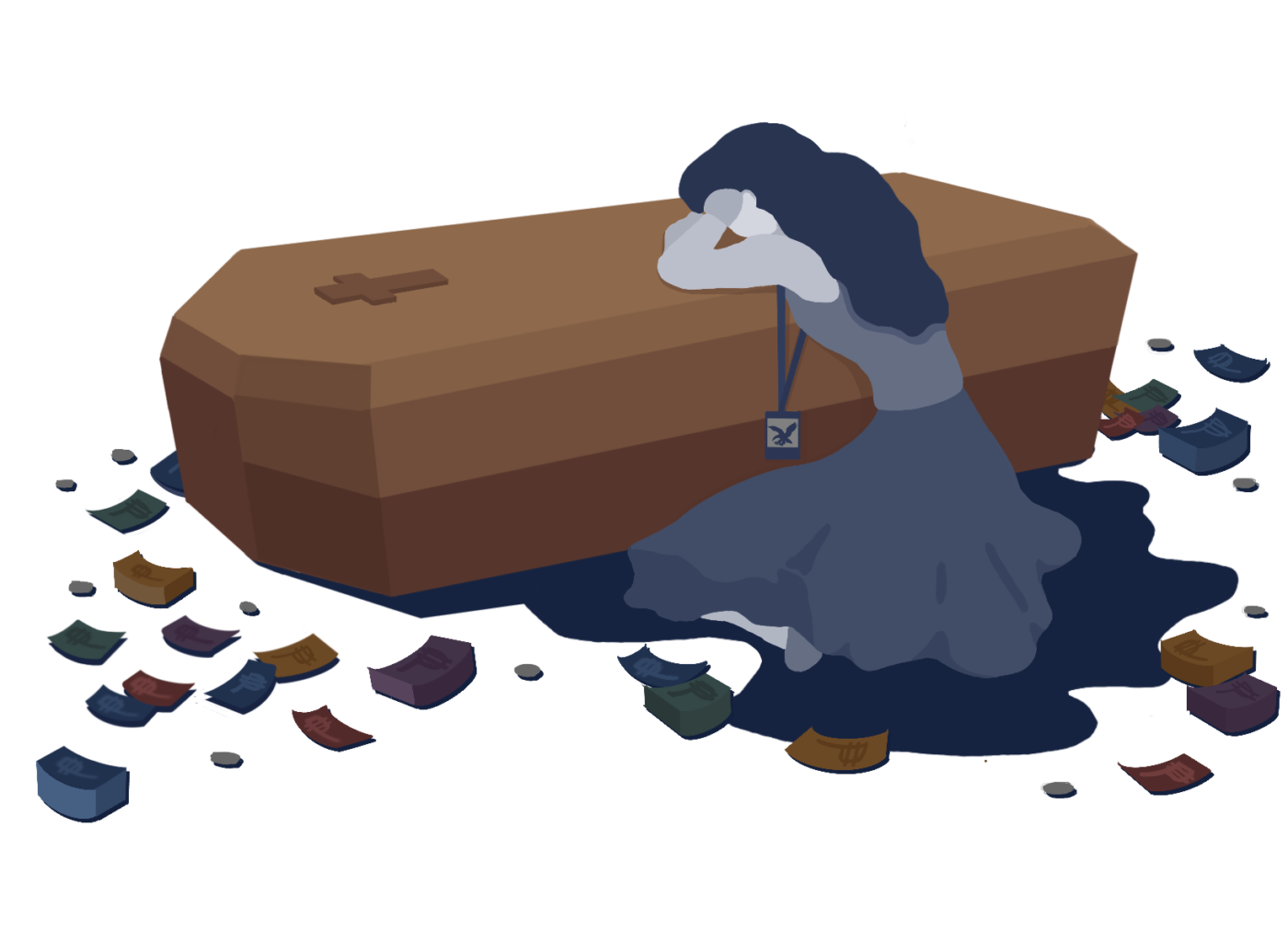

Amid this cautious approach, the financial and emotional repercussions of loss warrant increased community support—calling for a reexamination of the University’s efforts to aid its students’ recovery from grief in the educational landscape.

The cycle of grief

Sofia* was in the middle of her junior year when she received a call about her mother’s stroke. Upon hearing the news, she left Katipunan and rushed to her mother’s side at a hospital in Aklan. Despite her apprehension, Sofia remained hopeful that her mother would recover quickly and soon return to their family.

As a scholar, Sofia organized a fundraiser with the help of the Ateneo Gabay to pay for her family’s expenses. Initially, her family had intended to use the collected donations for her mother’s operation. However, two days after posting a call for donations on social media, Sofia held her mother’s hands for the last time.

“Sobrang lamig niya (She was so cold),” Sofia recounts. “Sobrang purple [ng katawan] niya. Parang hindi siya totoo.” (Her body was so purple. It didn’t seem real.)

Another scholar who lost a loved one while in college is Annet Tolentino (3 BS LM). During her sophomore year, Tolentino was resting at the University dorms when she received a phone call about her father’s passing, urging her to return home to Bulacan for the burial. Upon hearing the news, she described how she ended up in denial.

“I didn’t want to face the fact [that he was gone]. I was still in the negotiation stage where I thought that maybe this was all a dream. But at the same time, I wanted to be there for my father,” Tolentino shares in a mix of English and Filipino.

Although Tolentino’s experience follows Kübler-Ross’ Five Stages of Grief, Loyola Schools Office of Guidance and Counseling (LSOGC) Director Gary Faustino emphasizes that the pattern is not linear and may not apply to everyone.

To aid the process, Faustino explains that some Ateneans request a Leave of Absence to ease the burden of academic requirements and focus on recovering from the loss of their loved one.

Sofia and Tolentino, however, returned to school and busied themselves with their academics and other responsibilities to take their minds off grieving. They share that their motivations to excel in school were redirected toward honoring their late parents.

As time passed, Sofia and Tolentino eventually learned how to manage and navigate through their grief, yet this feeling would still manifest itself in the lingering reminders of the loss they faced.

For Sofia, she remembers the memory of losing her mother in class discussions on death or at the sight of hospitals. Meanwhile, Tolentino has grown to dislike paintings as they reminded her of her late father’s dream to be an artist.

With this, Faustino explains that the period of grieving cannot be capped nor measured in timelines.

The financial burden of deathcare

Beyond the emotional pain of loss, Sofia and Tolentino also faced the harsh reality of mounting expenses—from medical bills to funeral services—that quickly became unmanageable.

The average funeral costs in the Philippines typically range from Php 50,000 to Php 100,000, with additional expenses for cremation services or memorial plots raising these figures. For most families, the financial toll often starts with the substantial medical bills, which could lead up to a loved one’s passing.

In Sofia’s case, her mother’s passing led to over Php 270,000 in medical bills and funeral costs, but through the Ateneo Gabay’s fundraising efforts, her family was able to manage without falling into debt.

For others, the experience can be more isolating when the means of accessing support are unclear. To cover funeral and burial costs, Tolentino’s family had to rely on their limited savings due to the absence of insurance. As these savings dwindled, Tolentino turned to her friends and classmates for donations—a method she found more accessible than formal institutional aid.

Unlike Sofia, who leaned on the Ateneo Gabay’s assistance, Tolentino was unaware of the organization’s support services. “[The] Ateneo Gabay had welcoming activities, but in their defense, I wasn’t really active [so] I didn’t know they offered these kinds of support,” Tolentino acknowledges.

This difference highlights how students’ awareness of available resources can greatly impact their ability to seek help during times of crisis.

Ateneo Gabay President Rhyzen Joram Aguilar recognizes this issue, emphasizing that while support is available, the process can be daunting, especially for Ateneans who may hesitate to approach the Office of Admission and Aid (OAA). “[The process can be] intimidating for some because they require more formal requests, [like those needed] for OAA or professors,” he explains.

While student-led initiatives and community support play an important role in aiding students, these efforts often fall short in reach. As such, this reality underscores the need for the University to ensure that support systems are more accessible and clearly communicated.

Systems of support

The Ateneo’s offices and support systems serve as essential lifelines for grieving students, ensuring access to both emotional and financial assistance during difficult times.

For Sofia, a single session with the LSOGC was impactful, as they offered her the emotional validation she needed to process her grief. Beyond this, the LSOGC also bridges students with the OAA, ensuring that those dealing with grief are aware of the financial support available to them.

To help ease the financial burden following a loss, the OAA offers monetary bereavement assistance to scholars. For many grieving Ateneans, this financial support alleviates unexpected expenses, allowing students like Sofia and Tolentino to focus on their studies.

Aside from this service, Aguilar observes that after experiencing the loss of a loved one, some students even become financial aid scholars, subject to the evaluation of the OAA.

Despite the availability of these services, inconsistencies in policies across departments can undermine the effectiveness of such support. Tolentino’s experience with the University’s six-cut rule reflects this challenge of navigating rigid policies during periods of grief. “Yung cut policy, I’m so annoyed with that. It’s up to the professor, but it’s a serious situation, […] [yet] it’s only valid when a professor has empathy,” she remarks.

This policy, which makes no distinction between excused and unexcused absences, may fail to account for the realities of grieving students. Consequently, support can vary depending on each professor’s interpretation and enforcement, thus placing additional uncertainty on students.

Following this, Aguilar emphasizes the need for change. “Protocols need to be re-evaluated and updated to reflect the evolving needs of the student body. Especially in the aftermath of the pandemic, many of these policies have become outdated,” he states.

While the University has made strides in offering support, a more structured, compassionate framework that extends beyond immediate, short-term measures remains essential. This approach could foster a community rooted in empathy and genuine care, where support is not only available but truly felt.

*Editor’s Note: The name of the interviewee has been changed to protect their identity and privacy.