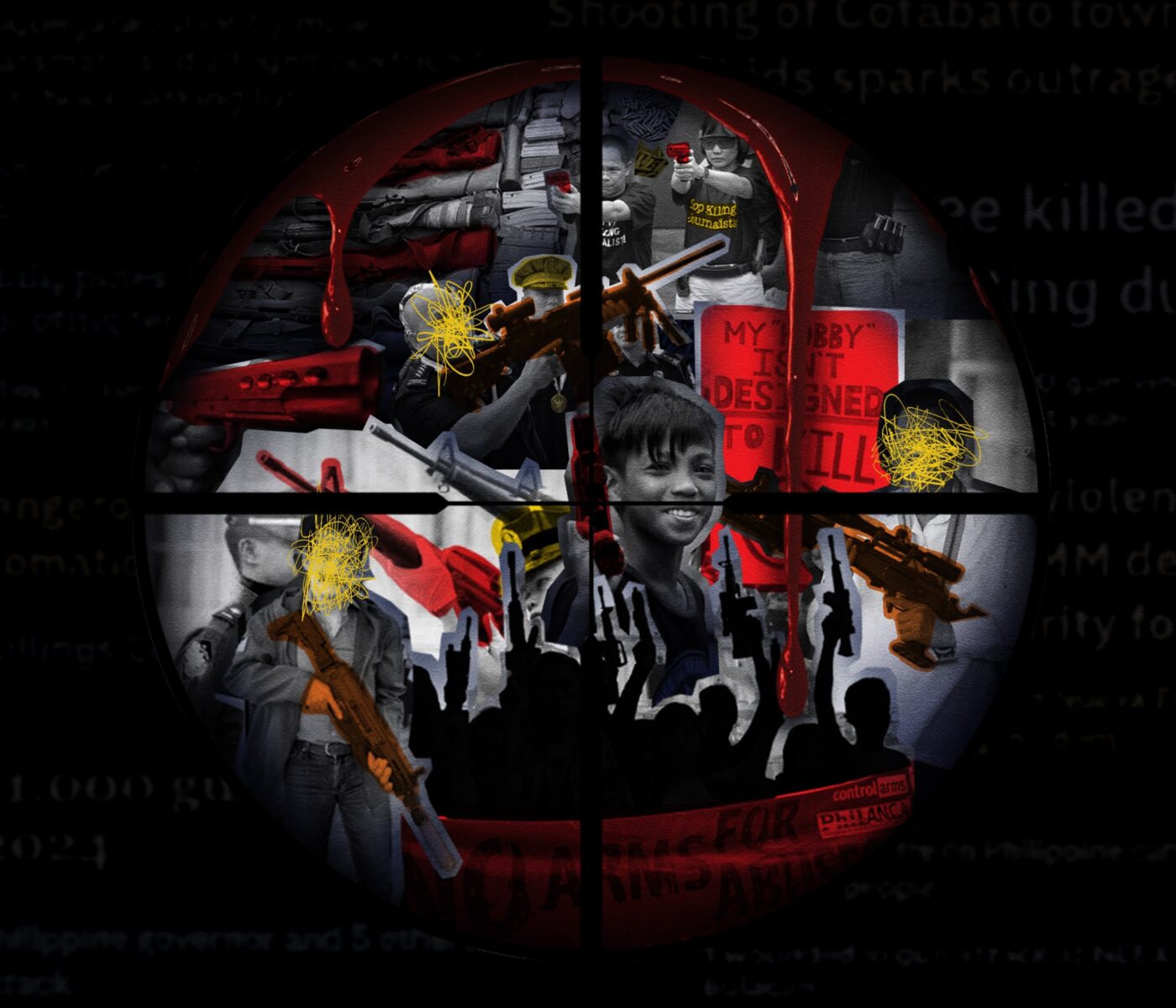

FIREARMS ARE met with apprehension in the Philippines as sectors with access continue to exploit increasingly loose regulations. Some political parties rally behind the security and self-defense that firearms supply to their owners, while others are intimidated by the capacity for violence that the mere ownership of guns poses.

Such circumstances set the background for debates surrounding firearm regulation amendments that grant civilians wider access to more powerful weapons. With sweeping changes, however, come questions on whether or not these provisions are counterproductive toward the security of the Filipino people.

Dodging bullets

The Philippines wields numerous laws to combat civilian gun casualties and regulate against misuse. Of these laws, the Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of the Comprehensive Firearms and Ammunition Regulation Act or Republic Act (RA) 10591 most thoroughly define the types of firearms civilians are permitted to own and for what purposes they may be used.

Alongside guidelines on licensing and registering, RA 10591 also covers regulations on carrying and owning firearms for civilians, government, and gunsmiths alike. Previous versions of these rules permitted civilians to own high-powered firearms like semi-automatic and automatic guns, but these were limited to light weapons when the act had taken effect in 2013.

Most recently, moves to amend RA 10591 came after the Philippine National Police conducted a study evaluating the effects of gun access laws on civilian violence. PNP spokesperson Colonel Jean Fajardo relayed that these revisions permit licensed private citizens to possess 7.62 mm-caliber semi-automatic rifles, which were previously limited to law enforcement and the military.

The announcement was released on March 4 this year and took effect in the same month. Notably, the study on which the amendments were based remains unreleased to the public, with the exception of the information provided by Fajardo in the aforementioned press release.

Since then, civilian and political opposition groups have protested these amendments, as such changes further endanger individuals by widening the possibilities for violence, terrorism, and criminality among gangs, black markets, and other parties with ill intent.

A history of violence

As of early 2024, PNP’s records show that the Philippines is home to over one million licensed gun owners, who overall own up to four million guns. Up to an estimated 500,000 guns still remain unregistered and unaccounted for. These firearms toll in around 5,000 gun-related incidents annually since 2022, with official government records already counting 808 as of March this year.

Discussing the context of the country’s political climate, Sociology and Anthropology Department Associate Professor Enrique Niño Leviste, PhD suggested that gun culture is closely rooted in—but not limited to—the use of violence or coercion by certain ruling families as part of their political machinery.

“Part of that machinery is the capacity to wreak havoc violently even in broad daylight—just the mere threat of it is potent enough. It’s part of the political machine as far as some politicians or families are concerned,” Leviste stated.

Electoral competition between local elite families has motivated some infamous cases of violence and deaths in the country. Among recent incidents include the attempted ambush of Lanao del Sur Governor Mamintal Adiong Jr. on February 2023, where four were killed, and the assassination of Negros Oriental Governor Roel Degamo in March of the same year, where five additional people were killed.

Leviste called attention to how such power plays might worsen with increased access to higher-caliber firearms. “[Amendments to gun regulation] would further reinforce or even magnify the structural inequalities that [Filipino citizens] continue to confront every day,” he explained.

Combatting mistrust

Despite the exploitation of firearm regulations by malicious political personalities and private citizens, gun ownership and citizen welfare are not necessarily irreconcilable. Leviste explained that expanding gun ownership with a sound legal framework can promote the use of firearms in a just way, rather than letting them remain as contraband used for illicit activities.

However, to this end, Leviste reiterated the role of regulation. “[Both the] national [and] local governments must regulate the activities of the police in their territories [and] ensure that proper authorities are equipped with technology and the know-how in terms of [monitoring] the use of guns,” he said.

Still, reservations from the public about the proliferation of violent gun culture or the continued general mistrust in law enforcement agencies are to be expected.

Hence, this most recent loosening of gun laws will hinge on effective policy implementation. In the Philippines, where firearms have been repeatedly linked to violence, particularly of a politically motivated nature, amending regulatory laws can only go so far when it comes to addressing the roots of gun culture.