THE 1987 Constitution is one of the main byproducts of the EDSA People Power Revolution, a culmination that signaled the transition from an authoritarian regime to a democratic rule. As the “highest law of the land,” the Constitution is a living manifestation of what its people stand for. For one, the current Constitution is founded on the goal of rebuilding democratic institutions, crafted in a way that prevents another president from extending beyond their given limits.

However, time after time, the country’s leaders have attempted to amend the Constitution. With power primarily concentrated in the two most influential families—both of which are vying for the highest position in the government—the current political landscape is diametrically opposed to what the Constitution has originally envisioned.

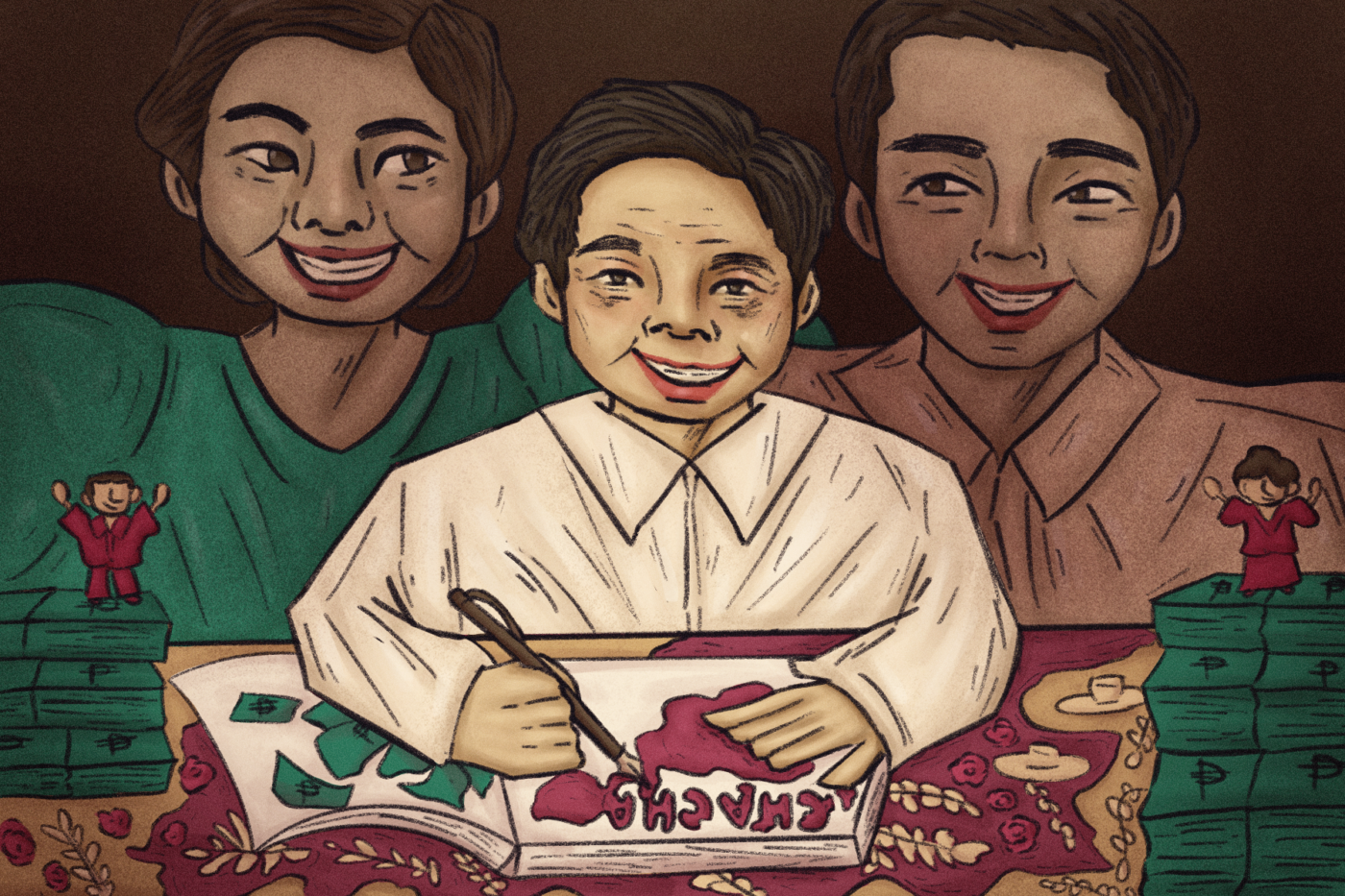

It takes two to Cha-cha

Cha-cha is a legal procedure in which the Constitution is revised via a People’s Initiative (PI), a constituent assembly (con-ass), or a constitutional convention (con-con). Currently, the Marcos administration is pushing for Cha-cha that seeks to propose amendments through the PI or the “power of the people.” For a national plebiscite to be scheduled, at least 12% of the registered voters must sign the petition. Additionally, the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) projects a Php 13 billion-budget for the Cha-cha referendum.

While the PI recognizes the participation of the people in proposing constitutional amendments, the recent initiative has been subject to scrutiny for its questionable methods of collecting signatures and support from electorates. For instance, the COMELEC is probing incidence reports of vote-buying and signature campaigns targeted at the general masses. People were often bribed or deceived into signing the document under the guise of an elections survey or a distribution of aid—further eroding the integrity of the PI.

Additionally, an ill-advised EDSA-pwera advertisement demeaning the EDSA Revolution was strategically aired on public television at a time when Filipinos were watching the 2024 Traslacion coverage.

Tunnel vision

The main argument for Cha-cha involves reforms that are geared toward strategically boosting the economy. Notably, the agenda pushed by Cha-cha supporters is the easing of economic policies in favor of foreign ownership in industries, initially restricted to a 60%–40% rule in favor of Filipinos.

The proposed amendments earned mixed reactions from economic experts and analysts. On one hand, increasing foreign direct investments (FDIs) by loosening economic restrictions were argued to be positively linked to “growth and development.” According to Cha-cha supporters, the protectionist economic model espoused by the Constitution cannot keep up with the trend of globalization. On the other hand, a study by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas economists suggests that relaxing FDI restrictions is not the “end-all and be-all of attracting investments.”

In the first place, economic growth should not be the sole yardstick of development, as implied by such approaches. Through development aggression, state-sponsored policies and projects are prone to excluding and displacing groups whose ideas of progress deviate from the hegemonic norm. Moreover, with 80% of the Congress belonging to dynasties, the Cha-cha is clearly an attempt to forward the self-serving interests of the power elite, raising eyebrows on who really gets to benefit from such amendments.

Taking the lead

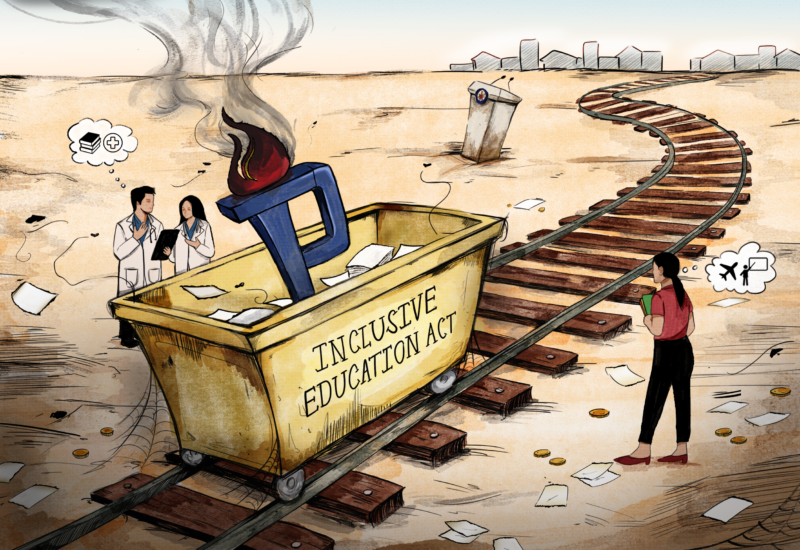

On its own, the Constitution has no teeth. Without public servants carrying out its stipulations, the Constitution is no more than a piece of paper—vulnerable to manipulation by those who are in power.

The EDSA-pwera advertisement blames the Constitution for the proliferation of injustices and inequality. However, the existence of business monopolies, the failure of the agrarian reform, and the broken education system—the social ills cited in the ad—cannot be magically reversed by constitutional amendments. In fact, the regulation of monopolies, rights of farmers, and rights to accessible and quality education are all entrusted in the Constitution. However, such stipulations have not been implemented nor enforced properly.

Our institutions, marred by poor governance and corruption, tend to favor only the elite. Our political systems are strongly overrun by a culture of patronage, in which “clients” vote or express support for a “patron” in exchange for tangible benefits such as money or community programs.

Moreover, Philippine politics is weak and pluralistic. Political parties are less likely to be bound by shared identities, ideals, or struggles. An apt example is the UniTeam, an electoral coalition created to win the presidential and vice presidential campaigns. As soon as the positions were secured, the Marcos and Duterte families no longer had a reason to keep the alliance, more so due to their pursuits of self-serving interests.

A government by the people, for the people

Rather than reforming the Constitution’s economic provisions toward hollow promises of social change, we need an ideological shift. We should seek to forget about personality politics altogether and instead clearly establish the principles and ideals of good governance. A key step in meeting these goals is engaging in conversation and dialogue with marginalized and sidelined sectors, understanding how their realities shape their worldviews, and realizing that our liberation is ultimately tied with theirs.

The Preamble of the Constitution alludes to a government that “promote[s] the common good” and “embod[ies] our ideals and aspirations” as a Filipino nation. However, the reality is starkly different from such a vision: The Philippines has been subject to curtailed freedoms and state-sponsored violence and impunity at the hands of the government, showing signs of democratic backsliding. We cannot trust our current leaders to pave the way to progress for the Filipino people.

Fundamental reforms necessitate a deeper reevaluation of what we collectively value as a nation. With this, we must constantly hold our leaders accountable, and realize that ultimately, the power of the people is more powerful than the people in power.