Trigger warning: This article contains mentions of sexual harassment, violence, and misconduct.

IT TOOK years after the end of World War II for the stories of Filipino comfort women to surface.

Maria Rosa Luna-Henson was the first Filipino to come forward with her experience as a comfort woman. Her story only came out in 1992, nearly 50 years after the end of the war. Since then, countless others have followed Luna-Henson’s footsteps and shared their accounts, bringing to light the torment that Japanese soldiers had physically and psychologically inflicted upon them. Despite such grave transgressions, Japan has willfully continued to disregard what their countrymen have done and has yet to make up for it.

When Japan started to seize control of the Philippines in World War II, they did more than just take advantage of the nation’s resources. The Japanese also exploited our people and did so in the cruelest way—subjecting Filipino women to sexual slavery. “Comfort women,” by etymology, is a phrase lifted from the Japanese word ianfu, which means a comforting or consoling woman. It was during World War II that it became a euphemism which referred to the group of women who were coerced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army in the late 1940s.

Comfort women were not only subjected to repeated sexual assault, as they also suffered harsh living conditions and were threatened with physical abuse or death during instances of resistance. It was estimated that about 1,000 Filipino women were forced into becoming comfort women, with only 70 of these survivors still alive today.

As the memory of these atrocious crimes linger today, Japan has yet to formally apologize for what they had done in the Second World War. When asked about their lack of acknowledgement regarding the Imperial Japanese Army’s use of brothels, the Japanese government regularly references their 1993 Kono statement. This blanket statement of remorse discusses their army’s use of comfort women in multiple countries like Korea and China, while notably leaving Southeast Asian states unmentioned. Thus, Japan has yet to direct a formal apology to Filipino comfort women and establish appropriate and sufficient reparations to truly prove their sincerity.

Although Japan—and even the Philippine government—continue to shun this part of history, many Filipinos continue to uphold the memory of Filipino comfort women in the hopes of one day getting the justice they deserve.

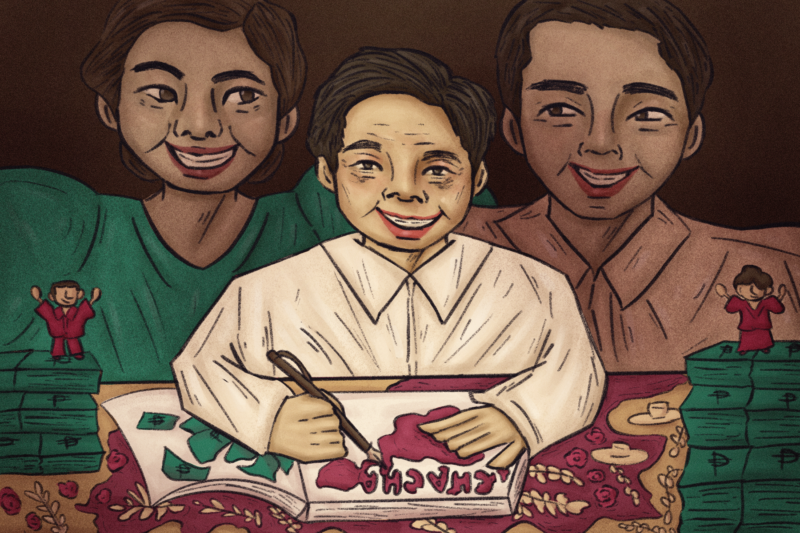

In 2017, a seven-foot bronze statue of a woman was placed along Roxas Boulevard, with her arms tightly clasping the front of her veil and her eyes covered with a blindfold. Her statue looked towards the sky, an expression of pain and longing carved onto her face.

Made by sculptor Jonas Roces and commissioned by the Tulay Foundation, the statue served to honor the thousands of Filipinos subjected to sexual slavery, serving as a reminder of an overlooked history being forgotten.

Later in 2018, the Filipina comfort woman statue was removed from its place in Roxas Boulevard during a drainage improvement project and was meant to be permanently relocated to Baclaran Church. However, before the statue could be returned, it was reported missing from the sculptor’s home and has purportedly vanished since.

Years have passed since the end of the Japanese Occupation in the country. However, surviving Filipino comfort women continue to assert their cause in other ways. For one, they lobby the Philippine government for the justice they deserve. Last March, the Members of the Malayang Lolas Organization made monumental progress with the reopening of the comfort women case in the Philippine courts. Under the direct declaration of the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the Philippine government was found to have violated the rights of World War II Comfort Women “by failing to provide reparation, social support, and recognition commensurate with the harm suffered.”

Such revision of history is not a new story in the country. Existing powers actively change narratives and hide the marginalized to maintain a legacy that fails to paint a full picture and take into account the perspective of others. Thus, while the declaration of the CEDAW is a welcomed historic step in protecting the dignity of Filipino comfort women, the years of abuse and trauma they have experienced point to the need for more work to be done.