THE SOUND of gunshots that hurled towards 17-year-old Kian Delos Santos echoed through the secluded streets of Caloocan and into the home of Nathan Villegas (1 BS MIS-MSCS).

Villegas was once a staunch supporter of President Rodrigo Duterte—the man behind the notorious drug war that killed Delos Santos. However, the news of his killing was perhaps the final nail in the coffin that helped turn Villegas’ back against Duterte.

The infamous war shed the blood of criminals and children alike, piling the roads with dead bodies and plastering them with cardboard cautionary signs. While the war intended to deter drug pushers from committing crimes, it has only instilled a deep sense of fear among Filipinos—worsening the already fraught political divide in the country.

Today, there exists a political environment rife with hostility among those from opposing ends and the present political order no longer “makes for a just society.”

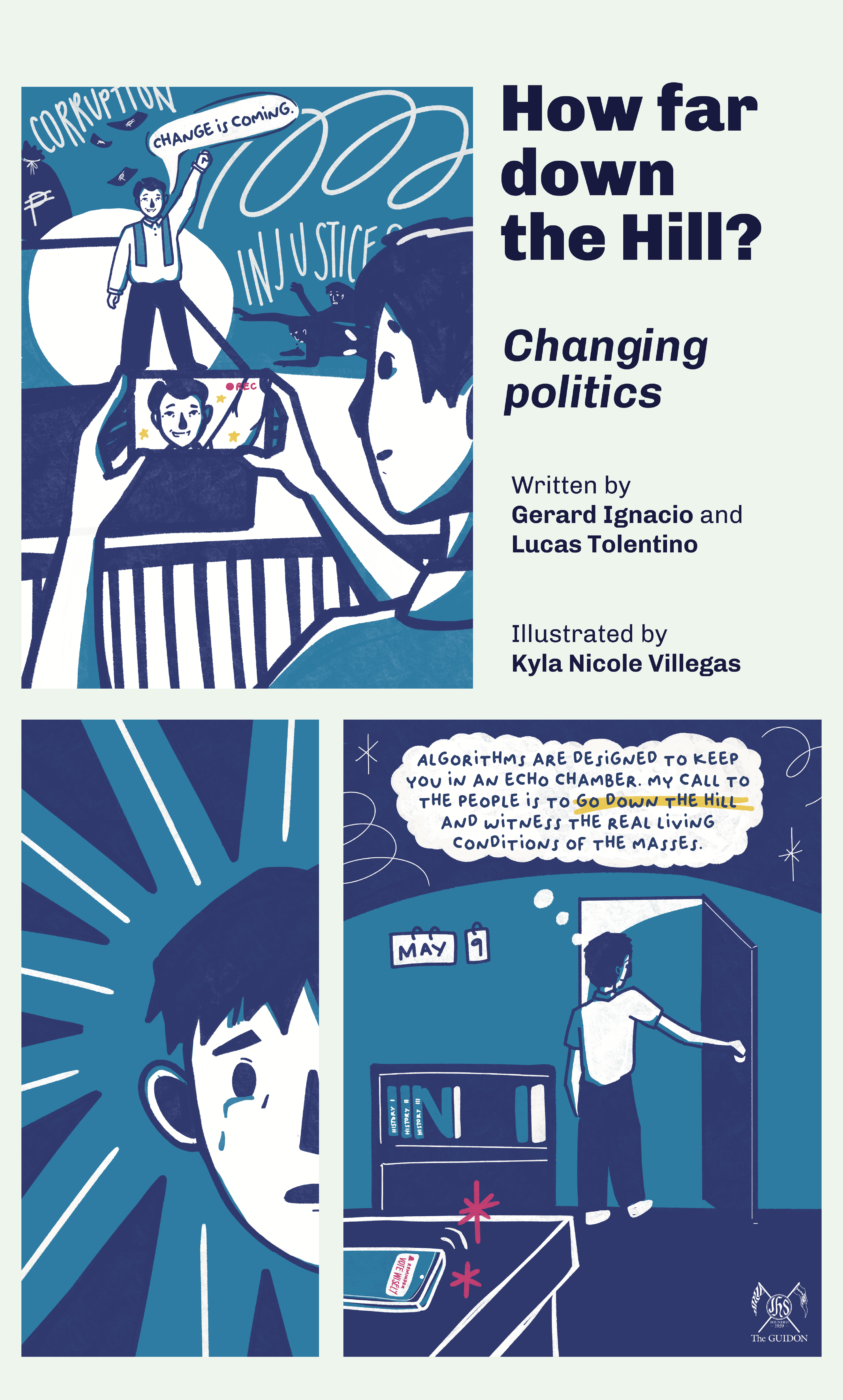

However, political ideologies rarely remain stagnant. They evolve and change just as the people who bring them to power do. Recognizing the politics of the past, young voters have the power to “seize the initiative in stripping away all forms expressive of an aristocratic or bourgeois mentality,” and bring themselves down from the hill in changing political flashes.

Turning the tides

These flashes have shined through in the life of Villegas, who was once a Marcos apologist and Duterte supporter.

Given the ever-growing prevalence of social media during the 2016 campaign period, Villegas recounts first hearing about then-Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte’s presidential bid through clickbait posts on Facebook. These posts, he acknowledges, were made with the intention of appealing to the common folk through captivating headlines—a tactic that other candidates did not use to their advantage.

Consequently, Villegas developed an instant liking towards this political underdog, vouching for Duterte to help the cause of the masses. Duterte’s unwavering resolve to target drug users through extrajudicial means also garnered the backing of Villegas, who was made to associate drugs with negative connotations as a child.

However, as Duterte’s underdog persona soon rose the ranks to become the next President-elect and his plans came to fruition, Villegas realized the many missteps in his agenda.

Seeing the war unfold made known to him the disproportionate scales of justice being served to Filipinos; small-time pushers continued to mount the death toll, while big-time drug dealers remained at large.

Ultimately, it was the death of Delos Santos—a teenager who was wrongly accused of opening fire during an anti-drug operation and thus shot down—which touched a nerve. Villegas was agitated upon hearing about the news, seeing as how both shared semblances as students.

When Villegas found out that Delos Santos’s final words were “Tama na po, may exam pa ako bukas (Please stop, I have a test tomorrow).” he shares that he felt as if a chill had gone down his spine. Slowly but surely, he then began to explore progressive organizations that pushed him towards new environments. He would then immerse himself in the lived experiences of urban poor communities, whose struggles, he observed, were rarely seen by both the mainstream and the communities themselves.

Today, Villegas believes that there is a certain nuance in interacting with basic sectors of society so as to make them aware of how the policies of the current administration barely align with their own interests.

In between fences

While most people have already finalized the lineup of candidates for their ballot, some continue to waver in their decisions. Such precariousness is most evident in the youth, whose political identities have yet to solidify.

According to Political Psychology Professor Erwine Dela Paz, PhD, there are many contributing factors that lead young people to shift their political ideologies.

For one, a public official’s rhetoric has a great bearing over the changing views of individuals. When certain messages are heard, they evoke profound emotions that move individuals to re-evaluate their politics.

In particular, individuals are commonly victim to “political exhaustion,” a state in which a person can no longer stomach the actions of incumbent leaders because these stray too far from the person’s own political ideals.

According to Dela Paz, “When you’ve already reached that point… that could be a triggering moment to shape your views, and sometimes it’s coupled with anger.”

Aside from anger, trauma is another likely factor that helps sway one’s political conscience.

English Professor Andrea Martin PhD, who specializes in trauma studies, says that social injustice at the hands of the government—like Delos Santos’ death—can help elicit “correct” empathy from citizens.

This concept does away with “putting oneself in another person’s shoes” and “appropriating an experience to oneself.” Instead, “correct” empathy recognizes the uniqueness of an individual’s experience and lends more concern towards the welfare of the social injustice victim.

According to Martin, “We are all human beings with hope… who are informed by our personal experiences… and some of us have the luxury of going out, you know, going to see some other cases that would broaden our experiences.”

Terms of emancipation

Political sway can also be brought about through interactions with those residing in varied political chambers.

For instance, Dela Paz says that the Filipino family—which is collectivist in nature—has a great bearing on a young person’s look at politics. However, as a child reaches a learning age, other institutions like their school begin to expose them to other political ideas. Consequently, children gradually develop their own personality and have a broader political spectrum.

Villegas talks about how, at a young age, he was easily influenced by the one-sided information found online. However, he came of age and gradually learned of other political perspectives through the lessons he learned in major school events.

Despite reevaluating his values, the ghosts of Villegas’ former self continue to haunt him from time to time: “It comes [back] to bite you… you would reflect on it… but what else can you do but to move forward?”

On the other hand, Villegas had also faced instances that have made the shift in his political perspective worth it in the end.

In particular, the regret he feels from his past has motivated him to be more critical about information that he is exposed to in his life. Villegas now firmly believes that whoever runs for public office, regardless of political side, must be thoroughly scrutinized.

“We should also hold the leaders that we put into the pedestal on [a] higher regard, on a higher standard,” says Villegas.

The right to discourse

While it is true that people should be proactive in learning about and even crossing over to the opposing political camp, these camps themselves have a role to play as well.

Thus, Villegas emphasizes the importance of straying away from the sense of elitism that the progressive side of the political spectrum tends to have.

He calls them to empathize with the other side: “‘Wag natin silang sabihin na mga bobotante. ‘Wag nating sabihin na ‘Hindi kami bayaran kasi nakakakain tayo sa Wildflour. Nakakakin tayo sa Starbucks.’ … Very elitist undertones kasi na ‘yun ‘eh…” he explains to voters.

(Let’s not call them bobotante. Let’s not say ‘We’re not paid because we eat at Wildflour. We eat at Starbucks.’ … Those have very elitist undertones.)

Cultivating an environment rich with healthy discourse is not “a process initiated from the top.” Instead, it is “a communal effort, a process brought about by the university as a community.”

Thus, in order for the calls to be heard, conversations need to be made–not only with those who remain on top, but also with the ones at the bottom who have stories to tell.

Ultimately, one’s position on the hill is never permanent. The stories of those like Villegas are but a testament to the changing flashes of politics that lead one to decide whether to stand still or trudge down hills.