In October last year, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) accused 18 Metro Manila-based colleges and universities of being involved in the Red October controversy, a supposed plot to oust President Rodrigo Duterte that was allegedly organized by communist groups such as the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the New People’s Army (NPA).

Brigadier General Antonio Parlade Jr. of the AFP claimed that these groups were “recruiting” students within these schools through Martial Law film screenings. Parlade stated that the goal for showing films about human rights violations during former dictator Ferdinand Marcos’ term was to supposedly encourage students to liken President Rodrigo Duterte to Marcos and “rebel against the government.”

The Ateneo de Manila University was among the schools accused. However, University President Jose Villarin, SJ refuted the AFP’s claims on October 4, 2018, pointing out the lack of evidence suggesting Ateneo’s exposure to such plots.

A day after the list’s release, the AFP admitted that some schools’ involvement in the Red October plot was still under “continuing validation.” Moreover, no coup against the President has been publicly announced or executed since the accusations were made.

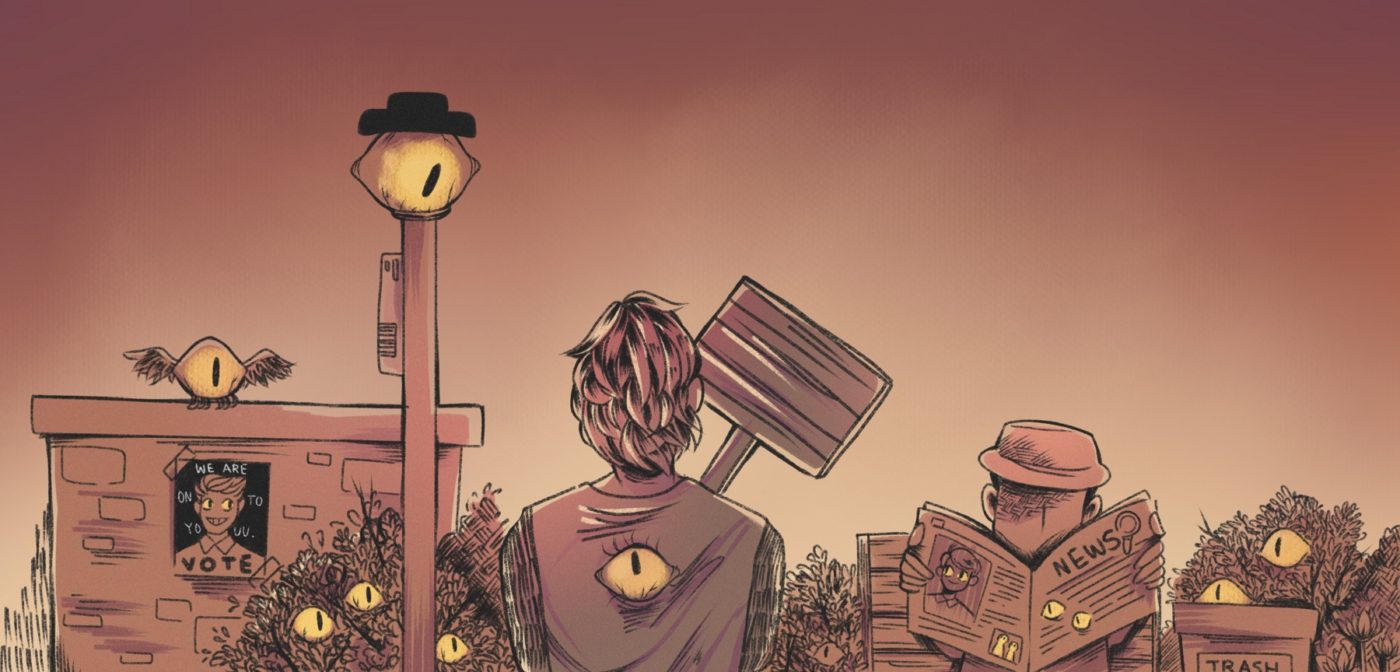

The administration’s public accusations of the infiltration of communist ideologies in universities have decreased, but a fog of unease continues to hang heavy in the air for student activists.

Shades of red

“Red-tagging” is defined as the persecution of entities based on alleged communist affiliations. Any individual or institution may experience being red-tagged and harassed by others who mistrust their political advocacies.

Human rights activists, labor union organizers, student activist groups, and other organizations critical of the government have been red-tagged and described as “fronts” for radical communist organizations. According to the nonprofit International Peace Observers Network’s (IPON) 2011 and 2014 journals, acts of red-tagging in the Philippines have led to state-enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings of marginalized groups and high-profile social activists; this is despite a lack of evidence connecting these entities to parties such as the CPP or NPA.

Kabataan Partylist (KPL) Representative Sarah Elago also stated in a Congress regular session last February 9, 2019 that the AFP uses the Reserved Officers Training Corps (ROTC) to “red-tag organizations, fraternities, student councils, and publications” through a supposed student intelligence network tasked with “monitoring the actions of progressive student and youth leaders” for the government.

While red-tagging in the Philippines is more commonly associated with political maneuvers to discredit the government’s opposition, the effects of such forms of harassment harm smaller organizations and politically vocal civilians as well.

A 2008 report by United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights Philip Alston revealed that during former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s term the AFP “[dismantled] civil society organizations” that were accused of being “front groups” for the CPP. Alston claims that this resulted in the extrajudicial executions of human rights defenders, trade unionists, and land reform activists.

The phenomenon of red-tagging politically critical organizations has also put student activists who have been accused of communist indoctrination in danger of further persecution.

Within the walls

Members of KPL and the One Big Fight for Human Rights and Democracy (OBFHRD) movement recount their experiences of being red-tagged within the Ateneo as a result of their vocal protests against the Duterte administration’s policies.

When it established its Katipunan chapter, KPL was met with suspicion from former Development Studies Assistant Professor Lisandro Claudio who accused the group of CPP affiliations. Claudio later clarified that while not all KPL members are also part of CPP, he believes it is an aboveground recruitment front for the communist group. Though some members of the Ateneo community such as former Union of Students for the Advancement of Democracy (USAD) Premier Lanz Espacio welcomed KPL Katipunan’s institution, student members of political youth groups continue to face harassment within the University.

Leah,* an active KPL member, states that she believes that the red-tagging of her organization is baseless. “Being a student activist doesn’t mean you’re allied with the CPP, NPA, or [the National Democratic Front]. We share some similar ideologies, but that doesn’t mean we’re allied with those who practice them,” she argued.

Due to the accusations of their group’s ties with radical communist organizations, student members of KPL were prevented from participating in former AFP Chief General Eduardo Año’s talk entitled “Protecting the People and the State” for the Ateneo’s Talakayang Alay sa Bayan class programs last February 21, 2017. Some members of USAD were also reportedly banned from attending Año’s talk.

The blocked students protested by wearing black to the forum and handing out flyers about Año’s alleged human rights violations and involvement with the disappearance of farmer-activist Jonas Burgos.

KPL member Mark* recounts that protesters of the group were blocked from entering the forum because they were labeled as “threats to security.”

Similarly, Jude,* a member of OBFHRD, shares his experience of being directly red-tagged. “I’m friends with a lot of activists. [My friends and I] were just talking [in the Zen Garden] when a student came by and called me a communist,” he says.

Prior to this instance, Jude reports that he’d observe the same student around campus eyeing him suspiciously as though “he was being followed by him.” He shares that in one instance, he was sitting with his friends at the Rizal Library Information Commons section, only for this student to approach once again and accuse him of “destabilizing the government.”

Jude also says that when he was a student at the University of Santo Tomas (UST), he would heare stories about fellow UST students who had received anonymous text messages warning them to leave certain organizations, lest these students be tried for expulsion on the grounds of suspected communist affiliations.

Though reports of red-tagging in Ateneo have been limited to accusations and suspicions raised against socio-political youth groups, Mark asserts that all forms of red-tagging are attempts at “delegitimizing” criticisms of the government’s oppression of disprivileged sectors. “We think that branding ordinary people as communist is an easy way to water down the struggles in the countryside. [The] fight for contractualization, fight against landlessness is being dismissed as communism,” he explains.

Sanggunian ng mga Paaralang Loyola ng Ateneo de Manila President Quiel Quiwa acknowledges how protests can become riskier because of red-tagging. “Red-tagging by civilians, especially from those who hold positions in institutions can also place students in danger given the current fake news culture,” he says.

Shielding students

Quiwa states that the Sanggunian called for all socio-political organizations within the Ateneo to work with the student government on joint projects to make stronger stands on national issues and organize safer protests for their student members. He also invites all students to approach the Sanggunian should they be red-tagged by any group or individual.

“Rest assured, the Sanggunian will always be a safe space for socially involved students and we will always protect the rights of [Loyola Schools] students,” says Quiwa.

Despite the acknowledged danger of being red-tagged during mobilizations, political youth groups and students within the Ateneo continue to organize around campus.

Director of the Campus Safety and Mobility Office (CSMO) Marcelino Mendoza reminds students that only accredited organizations may mobilize with official permits secured from the Loyola Schools.

The CSMO assigns every accredited student rally with a delegation of University security personnel with direct contact to the barangay, Quezon City police, and the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority. As an extra safety measure, any participation of non-accredited groups and individuals at official rallies must be reported beforehand to the administration.

In the event that these student-run protests or the organizations involved in these mobilizations are accused of communist affiliations, the CSMO is prohibited from disclosing information to the police—all reports of allegations must be forwarded to the Office of Student Services first, although the CSMO reports that this has yet to happen.

Student protesters of the Ateneo are further protected by Section 1, Article IV, of the Loyola Schools Magna Carta for Undergraduate Student Rights, which states that all students are granted the right to freely express their views and opinions “in a manner acceptable to the academic community.” Meanwhile, Section 4, Article IV upholds students’ “right to peaceably assemble and petition school authorities and/or government authorities for the redress of any grievances.”

However, because sociopolitical organizations such as KPL Katipunan are not accredited by the Ateneo and do not protest on campus, they do not receive the same protection granted by Section 5, Article IV, which prevents student activities such as peaceful protests from disruption by military or police personnel.

The protections granted to accredited sociopolitical groups do not extend to mobilizations organized by non-accredited activist groups such as KPL, regardless of communications with CSMO.

Despite the lack of official red-tagging reports within the Ateneo, students accused of being “reds” for criticizing the government remain under threat of persecution based on their advocacies. In this case, the mistrust of activists born from this culture makes it difficult for political dialogue to thrive and develop. Red-tagging does not only dilute the discussion of politics with far-reaching accusations, it makes the youth’s critical engagement with national affairs volatile as well.

*Editor’s note: The names of these interviewees have been changed at their request in order to protect their identity and privacy.