IN FULFILLMENT of his campaign promise to shift the Philippines into a federal government, President Rodrigo Duterte approved the draft submitted by the Consultative Committee (ConCom) tasked to review the 1987 Philippine Constitution.

Currently, the Philippines is under a unitary form of government, with the local governments deferring to the national level in terms of big decisions including budget and legislation. A shift to federalism would mean greater power and responsibility for local government units, in this case, that of each Federated Region. Under the proposed constitution, regional governments will have jurisdiction over income generation, tourism and leisure, and social services, among others. However, the national government will still make final decisions over matters of security, international relations, monetary policy, and trade.

Having expressed disinterest in continuing his administration, President Duterte has requested an additional provision preventing him from extending his term or running for presidency under the revised constitution. The draft now stipulates that the incumbent president must call for an election for the transition president and vice president within six months of the constitution’s ratification. This leaves all executive and transitory power to whomever is elected as president subsequent to the passing of the new constitution.

The transition president, along with ten members of the Federal Transition Commission, is tasked with formulating and executing a transitional plan. This involves the establishment of the entire federal government, along with the governments of all federated regions.

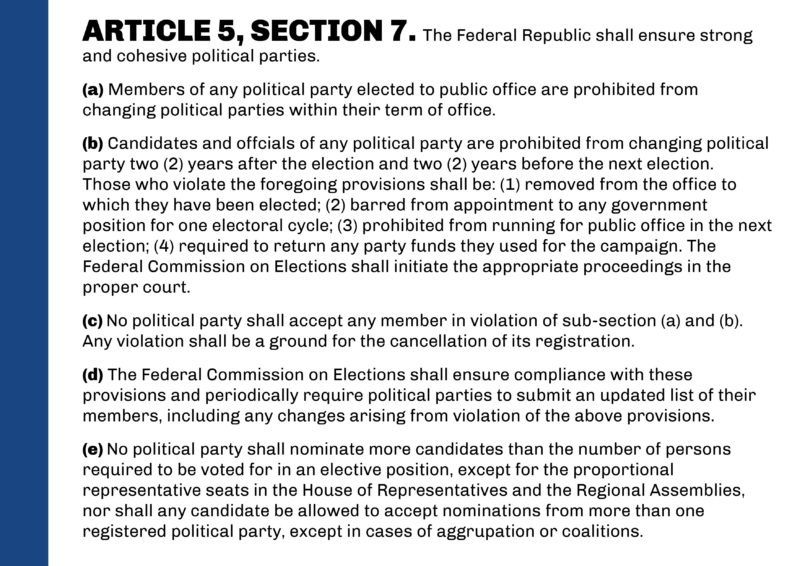

While there are articles in the proposed constitution that may enhance Philippine democracy, including Article 5, Section 7 on the strengthening of political parties, and Article 5, Section 8 on the banning of political dynasties, there are provisions which must be reviewed.

The change to come

Article 22, Section 7 of the draft states that the Commission can “exercise all powers necessary and proper to ensure a smooth, speedy, and successful transition,” including the ability to set its own budget, appoint necessary officials, and approve appropriate legislations. Therefore, the power to mold the future of the federated regions will be aggregated into a single group. Led by the elected president, the Transition Commission will create operating procedures for every branch of government, including the Constitutional Commissions and local governments.

The concentration of power to the chief executive in regards to appointing the Commission members creates an imbalance between the three supposed co-equal branches of government: the executive, the legislative, and the judiciary. The separation of powers is a cornerstone of democracy because it prevents government officials from abusing their positions. Yet, transitory provisions stipulated in the draft grant majority of the control to make necessary changes to the executive branch, partly because the President will also make the final decisions on the appointment of Transition Commission members. The draft does not contain any sections explicitly stating that the President is required to involve members of the legislative or judiciary branches in the transition process.

Inequality among the branches challenges the democratic system because it weakens the ability to exercise check and balance powers. The already heightened influence of the Duterte administration over other branches of government is evidenced by Congress’ reprioritization of charter change, following the President’s approval of the draft. This comes in contrast to the initial statement made by Senate President Vicente Sotto III, claiming that ratifying the federal constitution is not an immediate concern.

In addition, charter change brings about the opportunity for re-elections and term extensions. Previous attempts to change the form of government have been met with skepticism because of the possibility that incumbent officials may be able to use new constitutional rules to win additional years in power. Under the proposed constitution, members of the executive and legislative branches may serve a maximum of two terms in office, each term a total of four years.

The draft bears no provision preventing the reelection of officials who served their maximum term under the 1987 Constitution. This will open the floor for any and all incumbent public officials who wish to return to power following the implementation of the new constitution. Term limits are vital to the democratic process because they remove the possibility of an extended regime and ensure that younger generations will be able to represent themselves.

The proposed Democracy Fund under Article 5, Section 6 of the draft will allow private citizens to donate to the campaign fund of any candidate or party that they wish to support. Donors will also benefit from income tax exemptions, all while remaining anonymous. This has the potential to become a hotbed for constitutional money laundering, as private entities will be able to legally transfer money, increasing their influence among candidates that they support. Close ties between government officials and corporations may cause conflicts of interest, while donating corporations are likely to gain favor, especially when bidding to become contractors or suppliers for government projects.

Constitutional revision is a long and tedious process. Placing constitutional ratification as a Congressional priority will cause other urgent issues, such as the prevalence of violence and the failing national market, to be swept under the rug.

Culture of violence

All the while, the Philippines plummets further into a state of unrest as a culture of impunity continues to plague the country. The number of homicides continues to rise despite data from the Philippine National Police (PNP) which shows that other crime rates have decreased by 21.8% in the past year. The growing tolerance for violence has manifested itself most prominently in the cases of the eight local government officials who fell victim to murder in the past two weeks.

The slain politicians from different provinces include Mayor Antonio Halili; Vice Mayors Ferdinand Bote, Alexander Lubigan, and Al Rashid Mohammad Ali; former vice mayor Ferdinand Ramos; barangay chairman Alfredo Zapanta; and barangay councilors Michael Magallanes and Roel Mabano. All of the victims sustained fatal gunshot wounds, sparking other local mayors’ fears for safety. Presidential Spokesman Harry Roque dismissed claims that the President’s war on drugs has emboldened political operatives to eliminate their enemies, but acknowledged the possibility of political motives.

These acts of violence raise suspicion against Article 8, Section 18, the draft’s provision adding “lawless violence” as grounds for the suspension of the writ of the habeas corpus, along with “invasion [and] rebellion.” The first draft, having been approved by the President, bolsters the administration’s vision for a safer Philippines, and a peaceful Mindanao. However, concrete solutions safeguarding national security and peace have yet to be found.

In the same way, the administration has consistently maintained its limited liability for the extra-judicial killings in the war on drugs. Despite UN Human Rights experts renewing their pleas for the government to probe the case, President Duterte responded by spewing insults and threats at a special rapporteur. In June, Duterte addressed calls from different human rights groups urging him to serve justice to the families of the victims of the drug war, saying, “If you think that you can get justice simply because you lost somebody who’s a bullshit into drugs, I’m sorry to tell you I will not allow it.”

The administration’s encouragement of police brutality places peace and safety in the backseat as lawless violence ensues. Conflicts between law enforcement and the Council of Human Rights arise as the controversial Makati strip search incident strengthens the public’s suspicions about the ConCom draft’s promises to protect human dignity and uphold the welfare of women. Coupled with the police’s refusal to hold a transparent investigation on this issue, the image of national law and order at play remains askew.

These recent events are pivotal to the perpetuating view that peace can only be found beyond mountains of bodies. While the approval of the Federal Constitution draft is ongoing, the draft’s promises of peace remain far-fetched for as long as the culture of violence persists.

Instead of enacting substantial policies to concretely address this issue, government leaders focus their efforts on changing the terminology of the provisions to address it. The ambiguity that surrounds the loose definition of “lawless violence” on Article 8, Section 18 gives the administration the advantage to interpret the provision to their liking. This highlights the possible risk of misuse—a way to allow the executive office to gain all powers. Although vigilantes are seen as the perpetrators of violence, they are clear manifestations of the executive office permitting impunity to thrive.

The depreciating peso

“Now the economy is in the doldrums,” said President Duterte in a June 22 speech at the National Information and Communications 2018 Summit in Davao. This was the President’s response after the Banko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) hiked interest rates last June 20 by 0.25 basis points to 3.5 percent from May’s 3.25 percent due to inflationary concerns. Economic doldrums are characterized by periods of inactivity and stagnation. More specifically, Duterte was referring to the slump of economic activity in the provinces despite our economy’s 6.8 percent growth in the first quarter of 2018.

The President deemed the illegal numbers game, jueteng, to be an economic remedy. After all, “if there’s jueteng, […] at least money goes around. Some people will get hungry, others will be able to eat, [but] there’s [still] commercial activity,” he told the Inquirer. Duterte was arguing for the chance for equitable growth throughout the country.

However, while the President believes that jueteng—regulated or not—grants money the chance to circulate, University of the Philippines Economics PhD candidate JC Punongbayan says otherwise. “Aside from being illegal and nontaxable, jueteng is hardly the prime mover of economic activity in the provinces, no matter how big an industry it may seem,” argued Punongbayan. In organized gambling, no real value is exchanged, and financial capital moves upward in an extreme manner—to the extent that capital no longer flows back down. Organized gambling rarely sees wages, interest on savings, and public services funded by tax revenues, among others.

In the midst of these economic issues, the executive branch approved a draft of the proposed charter that allows for a shift to a federal form of government with the ability to significantly impact regional economies. Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque jumped on the matter, stating in a press briefing in Cagayan de Oro that “our economic growth is not evenly distributed,” and that “provinces are lagging

behind in terms of progress and projects.” Consequently, federated regions are deemed to be the solution to the uneven distribution of economic gains.

While many regions are being left behind, a federal form of government is no guarantee of prosperity for Filipinos in the provinces. In an interview with One News’ The Chiefs, Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Ernesto Pernia warned that the regions are not ready to shift towards federalism. He said that “expenditure will be immense if we go to federalism, and […] that the fiscal deficit to the GDP ratio can easily jump to maybe 6% or more,” which will “wreak havoc in terms of our fiscal situation.”

According to the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), this expenditure will range from PHP 44 billion to PHP 72 billion, assuming that the existing bureaucracy will not incur additional costs. University of Asia and the Pacific (UA&P) Economics professor Victor Abola told Rappler that the Philippines could suffer the fate of sky-high inflation should it shift to federalism, similar to the federal states Brazil and Mexico. Bernardo Villegas, another economics professor at UA&P, also warned there would be a “big gap” in the ability of federal states to implement all projects and spend funds, especially since “the local level is not very transparent in using funds.” Pernia thus cautions that the government cannot afford to be rash, suggesting that they must “do [their] homework first.”

While the constitutional draft has its merits, it fails to address a number of the country’s most pressing issues such as widespread lawless violence and the depreciation of the peso. The draft streamlines the concentration of executive power. The draft also allows for the suspension of habeas corpus in times of lawless violence—a noteworthy provision given the murder of public officials and the extra-judicial killings which characterize the war on drugs. Meanwhile, prominent economic professors and institutes have refuted the administration’s claims that federalism will serve to decentralize economic growth.

The draft’s provisions have the potential to inflict further damage on the already weakened state of democracy in the Philippines. There is hope that federalism will bring about great change in the Philippines, but only time will tell if these changes are for the better.