CHINA’S QUEST for soft power began over a decade ago when its government started funding Confucius Institutes. These non-profit learning centers aim to promote both Chinese language and culture.

However, these institutes have come under fire from Americans for refusing to address any unfavorable talk towards the Chinese government. Not quite as subtle as America’s long-standing overtures through Hollywood and popular culture, Confucius Institutes rack up criticism for being both funded by and sympathetic to the Chinese government.

Their presence, to some academics, feels like an attempt at infiltrating international and popular discourse from the impervious space of the academe. The alleged goal? Propaganda, but tailored to a foreign audience.

Chinese Studies lecturer Lucio Pitlo III quantifies Confucius Institutes as “no questions asked, [an attempt to consolidate] soft power” by “presenting a more benign image of China.”

On the other hand, Pitlo argues that China is “put between a rock and a hard place” in this regard, explaining that “If [China] tries to use its culture to promote its image, it is called out. If it uses too much of its economic largesse to support its soft power, its called out.”

Regardless of the goals that may have informed the Chinese state’s funding of Confucius Institutes, studies in the United States (US) have found that they have done little to improve China’s overall image. Similarly, Filipinos still put the most trust in the US, with China and Russia at the opposite end of the public opinion’s spectrum. This means that if China’s goal is to find a way to influence rather than to impose, then this worldwide overture has not shown much result.

Coined to explain the singular influence of the modern American empire, Ben Nye’s “soft power” signifies the infiltration of the very identity-formation of other states. This is done largely through the projection of an ubiquitous and charismatic presence through media, values, culture, etc. This charm offensive, along with its unmatchable military strength, allowed the US to to maintain its leadership role within the international community. However, now that America seems to regress from the world stage, China is looking to step up.

The ‘all-powerful’ Xi Jinping

A shining red light looms over the globe as China further establishes itself as the new world power in the wake of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 19th National Congress. Held once every five years, the Congress is held to elect its leaders, amend the party’s constitution, and draw a concrete vision for the next five years.

One of the most notable parts of this year’s event was the induction of “Xi Jinping Thought,” named after the current President, in the CCP Constitution. This feat has only been achieved by two other leaders: Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. With the full support of his party, President Xi is more emperor than president: Vastly powerful, unopposed, and ready to lead China into a golden age of development, prosperity, and hegemony.

According to Pitlo, Xi Jinping Thought is “an attempt for China to refine its ideology and its current economic and political set up as something suitable for [today’s] China.” As the guiding principle of the CCP, Xi Jinping Thought—a modern revamping of China’s brand of socialism, is a move towards presenting China as the new hegemon to emulate. Xi declared that the CCP’s ideology, now dictated by his thought, offers “a new option for other countries” as China opens up to the world.

China has coupled this with a contempt for Western democratic systems, claiming that the Chinese model avoids “the endless political backbiting, bickering, and policy reversals which are the hallmarks of liberal democracy.” The Party’s ideology chief, Wang Huning, is certainly a firm believer of this. His 1991 book America against America railed against the individualism and self-interest of the American system.

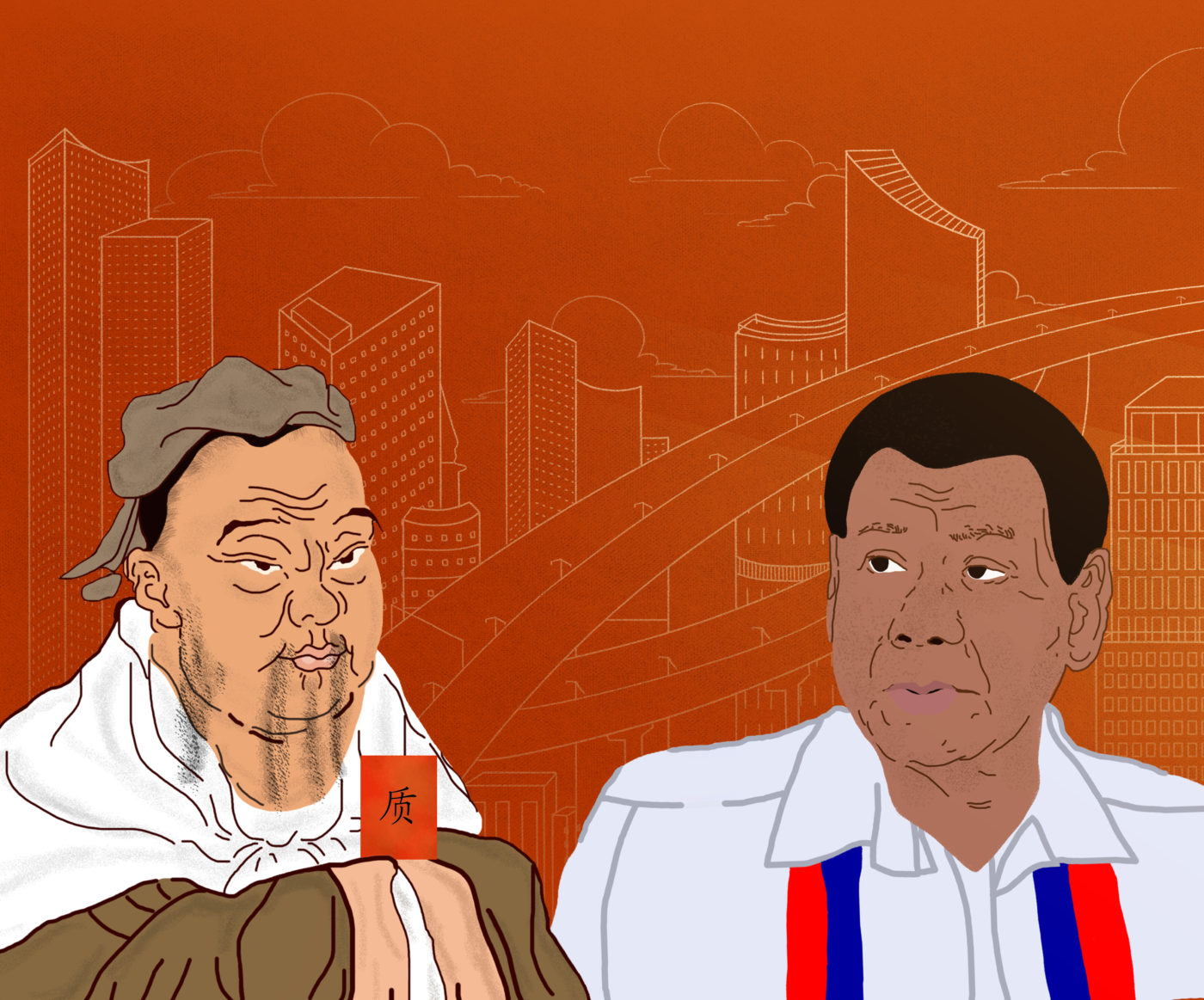

As China looks to Southeast Asia to cement its leadership role in the international scene, the Philippines finds itself trapped in a struggle between two powers: China and the US.

Caught in the middle

The Chinese model has certainly caught the attention of the Partido Demokratiko Pilipino-Lakas ng Bayan (PDP-Laban), the Philippines’ ruling party, and has expressed its commitment to learn its ways. Members of PDP-Laban, including Senate President and PDP-Laban President Aquilino “Koko” Pimentel III, have regularly made trips to China to forge closer ties with the CCP.

Pimentel has also expressed admiration for the fast pace of Chinese economic growth while touring the province of Fujian, the home province of the majority of Chinese-Filipinos. “I am very impressed with Fujian. They are not at the center of the country politically or economically, but they still managed to do very well,” he says.

Moreover, the Philippine government is heeding the siren song of economic aid and is looking at rapprochement with the upstart power. For example, President Rodrigo Duterte’s vision of a “golden age of infrastructure” relies heavily on a USD 167 billion loan from the Chinese. Although they have been transparent about it, the Duterte administration has not been so clear on the conditions and implications that come with this loan. At a 10% interest rate, this USD 167 billion loan is estimated to put the Philippine GDP ratio at 197% in ten years, the second worst in the world. This debt gives China financial leverage over the Philippines, making the country susceptible to undue Chinese influence.

Because of this, Magdalo Partylist and opposition representative Gary Alejano, is wary of Chinese money. “The more [the] Philippine economy is exposed to China, the more our economy becomes dependent [on] them and the less our power will be to assert our interests pertaining to our territorial conflict in the West Philippine Sea,” he says in an interview with The GUIDON. Although Alejano welcomes engagement between China and the Philippines, territorial disputes should not be sidelined.

Alejano does not have a high regard for Duterte’s foreign policy in this respect. “The impact of this silence, inaction, and subservience with regards to the West Philippine Sea is felt even more by our fellow Filipino fishermen whose livelihood depends largely on the disputed areas.”

Indeed, the destiny of the Philippines is intertwined with China’s. Pitlo characterizes this polarizing spectrum as one that most Southeast Asian countries struggle to reconcile.

“We are put in a difficult position. I think no country wants to take sides in the contest between these great powers, but we also don’t want them to have [any] understanding that leaves us out of the picture,” Pitlo says. He also says that the Philippines’ long-running alliance with the US has allowed it to focus largely on domestic issues, a security that not all countries can boast.

Complicating that matter is the fact that at the forefront of the domestic agenda is the economy and that China has been a key player in that arena. However, the two hegemons blur the lines of these designated relationships: “If you allow [US] troops to come here, for good or bad, China will see it aggressively, no way for China to see it otherwise,” says Pitlo.

What do you think about this story? Send your comments and suggestions here: tgdn.co/2ZqqodZ