*All names of family members have been changed, and the locations of the killings omitted to protect their privacy.

It was Annie’s birthday that December morning, a year ago. She was turning 10, and despite her age, she understood that her family could not be complete. Her mother was in prison, taken by the police days earlier when they could not locate her father, Tatay Romy, who was in hiding in Manila.

Romy knew he was a dead man once he came home. He had been warned he would be killed the second he stepped back in the village. Yet on that December morning, Annie awoke to see him in their kitchen cooking spaghetti. Romy’s mother, Lola Rowena, was terrified to see him, but all he could say was, “Namimiss ko na pamilya ko, at birthday ng anak ko (I miss my family already, and it’s my child’s birthday).”

So there he was, serving spaghetti to his seven children before they were to leave for school. Then suddenly they all heard a sudden crash as a raiding team broke down their wall, and six men came charging in.

The children were dragged outside, screaming and crying. Crystal, one of Romy’s daughters, threw herself at her father. “Pa! Papa! Pa!” she cried again and again as she clutched him with her tiny hands, till one of the men grabbed her and tore her away from him.

Then right in front of her, as her father begged, “Parang-awa niyo na, marami pa akong mga anak (Have mercy, I have many children),” the armed men shot him—in the head, in the chest and in the stomach—and then left him lifeless on their couch, holes in his body, blood oozing out.

This account of the story of Annie and Crystal was told to Project SOW which stands for Support for Orphans and Widows, a joint effort of St. Vincent School of Theology, De Paul House, and the Ina ng Lupang Pangako Parish in Payatas in Quezon City.

The accounts of the families mentioned in this article were documented by Project SOW and Rise Up for Life and for Rights Philippines, two organizations that help the families left behind by drug war victims recover, emotionally and economically, from the loss of their loved ones.

Psychologists and social workers say the left-behind children are going through a complex trauma arising from the violent deaths of fathers and sometimes mothers as well. They also face a stigma in their communities from having parents branded as criminals. And on top of these, the children have also sunk deeper into poverty now that the breadwinners are gone. And yet there is no support from government social welfare agencies for the orphans, as national social welfare officials point the finger at local offices which have not done anything for these left-behind children.

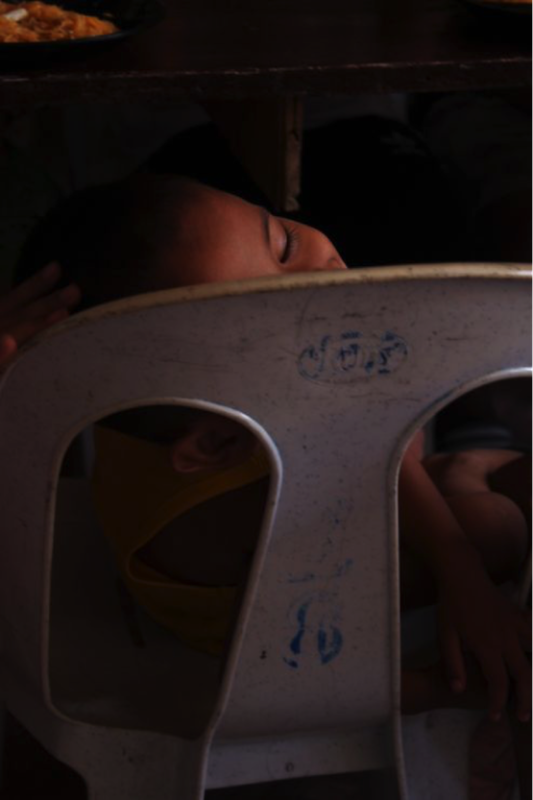

Photo by Kaela Malig

Psychologists and social workers from Project SOW and Rise Up were able to document the stories through processing and profiling sessions with the left-behind families. The writers were allowed to attend and observe the families during intervention sessions and were given an avenue to casually interact with them.

The families come from Caloocan, Navotas, and Quezon City—three municipalities in Metro Manila that have the highest drug incidents within their barangays, as recorded by the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency in 2014.

From the 14 families that were documented, 45 orphaned children are already affected. The local non-government organization Children’s Rehabilitation Center (CRC) that helps children and their families who are victims of state violence told CNN Philippines in August 2017 that the estimated number of children orphaned by the current administration’s campaign against illegal drugs is now roughly between 18,000 and 28,000.

“It’s very hard to imagine how the child could continue on with this kind of situation,” said psychologist Grace Brillantes-Evangelista, chair of the Department of Psychology of Miriam College. Despite this, there is still little initiative from government agencies and different organizations to create specialized social welfare programs for them and their families.

Left-behind families are afraid to approach any government institution like the Department of Social Welfare and Development or even their own local barangay for help.

They are afraid of approaching the very people who could be responsible for their loved ones’ deaths, said Fr. Daniel Pilario, C.M., director of Project SOW, which aims to provide community-based rehabilitation services to the left-behind families in Payatas B, Quezon City. Majority of the families have resorted to hiding, Pilario said.

With the drug war death toll at over 12,000, according to the Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates, the anti-drug campaign continues.

Drug addicts or loving fathers?

Joyce and Henry couldn’t have been any happier for their parents Ronald and Hera who were about to get married after years of living together. Ronald was kind, generous, and never failed to put food on the table, according to the stories told to the social workers.

But the wedding never took place. One day, the family heard neighbors shouting “Patay na si Ronald (Ronald is dead)!” Hera couldn’t stand staying in a place with so many memories of her partner and one day ran out of their house and out of her children’s lives. Joyce and Henry are now staying with their 69-year-old grandmother, Lola Kyla.

Jake, a young father, had just returned from a late evening out to buy milk for his eight-month-old son Jackson when 15 masked men—some in police uniforms, others in civilian clothes—suddenly barged into his parents’ house for a buy-bust operation, or so they say.

Jake and his own father Fred were forced down on their knees, screaming and begging for their lives, as guns were pointed at them, according to the family members who gave the account to social workers. Just a few minutes later, both of them were dead. Jake was last seen clutching a box of formula milk to his chest.

Remembering the first death anniversary of Fred and Jake, Nanay Jane, Fred’s wife, told a crowd how Fred would always be the one to stay at home and take care of the children. While she was busy at work, Fred took Jake’s four younger siblings to school in the morning and fetched them in the afternoon every single day.

The family had neither money, toys nor a big house to live in, but what the children were proud of were lice-free hair courtesy of Fred who would line them up to pick lice off their hair, his own gesture of love. Healthy scalp, trimmed hair, and even cut and groomed nails were the services Fred’s children received from him.

When his family had nothing to eat and Nanay Jane’s salary simply wasn’t enough, Fred was forced to score illegal drugs for people who did not know where to find some, Nanay Jane told the social workers. “Kalam ng bituka (It was out of hunger),” stressed Nanay Jane. But he stopped doing that and soon surrendered himself, even before President Rodrigo Duterte was officially inaugurated, when he was promised a second chance by barangay officials. He found himself a decent job and even served as barangay tanod (village guard) for a while.

“Pagkalipas noon, mga ilang buwan, ‘di namin sukat akalain na sa pagsuko niya, ikakapahamak pa naming buhay (From then on, after a few months had passed, never did we think that his surrender would endanger our lives),” Nanay Jane said.

At a forum, Pilario said, “They [the victims] are not rapists. They are, in fact, fathers who can bring spaghetti, no matter how difficult, for a daughter who is celebrating her birthday.”

“Call them drug addicts. Call them animals. Call them less than human, but for these children, they are always their loving father,” Pilario said.

To be concluded.

(Kaela Malig and Andrea Taguines are AB Communication seniors at the Ateneo de Manila University. This report is an abridged version of the thesis they submitted to their adviser Andrew Ty.)