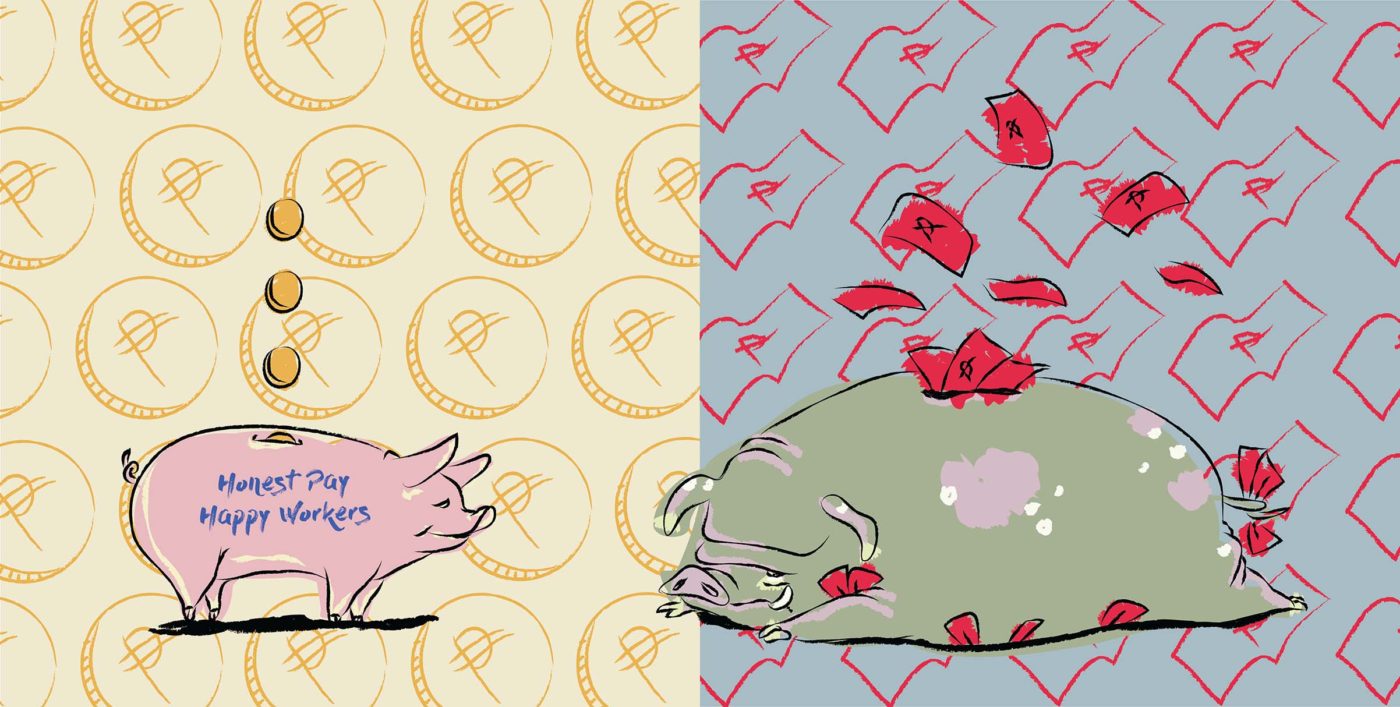

It is not unusual to think that businesses only act upon their own self-interest. After all, it is the duty of business owners to maximize profits. However, when businesses place profit maximization as the sole end and greed takes hold of the situation, problems start to crop up. What is usually left is a set of decisions that look good on an income statement, but in reality presents us with ethically questionable business practices that come with tragic repercussions.

An example that comes to mind is the Kentex Manufacturing factory fire that happened on May 13, 2015 in Valenzuela City, which killed at least 72 workers. It was found that the building had few exits, barred windows, and no fire safety training. Before the factory workers met their deaths, they were paid below minimum wage and had to endure being constantly exposed to chemicals.

This kind of anecdote is a manifestation of the need for business ethics. There is little justification for some of the negative effects of the blind pursuit of profits; these have to be kept in check, as businesses are not operated in a vacuum. They are a powerful aspect in society and business owners’ decisions and actions have real, lasting effects that trickle down to every individual.

Giving in to reckless business practices in the name of higher revenues and lower costs is one temptation many Ateneans will face in their professional lives. In the pursuit of producing graduates who are persons-for-others, it is important that the Ateneo guide its students to be ethical in their business endeavors while they are still under the supervision of the university.

Teaching business ethics

Anyone who has checked the official curriculum of John Gokongwei School of Management (SOM) majors in the Ateneo will know that although specialized subjects such as finance, accounting, and marketing are taught to SOM majors, business ethics does not exist as a separate subject.

John Gokongwei School of Management Student Enterprise Center (JSEC) Moderator Alyson Yap recounts that the rationale for this is that business ethics should be integrated in class. “Before, there was a separate class on business ethics, pwedeng elective. However, the push of the dean before was ‘let’s not have a separate business ethics [class] because the idea is dapat in every class, integrated siya,” he said.

Ethics as a general topic is covered by the twelve units each of Philosophy and Theology, classes that every student in the Loyola Schools must take. These classes are meant to be accessible to everyone and serve to build a sound base of good moral character and proper ethical judgment in any situation. Yap indicates that business ethics is simply “[The] intersection between Ateneo’s core curriculum and JGSOM’s business curriculum.”

Controlling self-interest

With JSEC serving as the initial avenue for business for many Ateneans, Yap also raises concerns with how business ethics is practiced within the program. One of them is failure to comply with ordinances and standard business practices, out of ignorance on the part of the JSEC stall owners. This means that some JSEC stall owners might be unknowingly in violation of the necessary compliances that are needed in operating a business, such as having to register the business with the local government unit and paying the appropriate wages and benefits to employees. These ordinances, Yap pointed out, are exclusively taught in the Legal Management program, with subjects such as Law on Business Organizations, Taxation, and Labor Law.

In order to curb ignorance of the law on part of the JSEC stall owners, they are required to comply with all legal and ethical regulations. “I force them. Hindi nga naman magandang tingnan kapag JSEC tapos ok lang na hindi registered (JSEC won’t have a good reputation if the businesses aren’t registered),” says Yap, “Kailangan magregister, kailangan magbayad ng tax, etc. Kasi kung hindi, madali lang makahanap ng tao and just pay them below minimum wage (Registration is mandatory, paying of taxes is mandatory, etc. If not, it’s easy to just find someone and pay them below minimum wage).”

Another problem is that although the JSEC owners are already made to follow ethical business standards, there are still some that choose not to comply with the mandatory regulations, particularly with regards to the payment of PhilHealth and SSS benefits for the employees. Yap recounts that there were three stalls in the last school year’s JSEC line-up that failed to pay the mandatory benefits and one of them had a pregnant employee who only found out she had no PhilHealth contributions when she attempted to claim her benefits.

In cases where the payment of benefits are not fully realized, JSEC revenues generated from rent is used to pay the benefits and the students are given hold orders until the payables have been settled.

Free and fair

The School of Management Business Accelerator (SOMBA) program also acknowledges the gap between the ideal and the reality in practicing business ethics. However, rather than forcing compliance, SOMBA teaches its students every option they can take in achieving the necessary ends for their businesses. Ultimately, they are left to decide for themselves when the time comes. According to SOMBA Program Director John Luis Lagdameo, “ideally what you want to do when you engage in a business is [to be] free and fair. [This means] everybody’s on a level playing field, so there’s opportunities and chances.”

Lagdameo cites the example of having to register the business, where students are often presented with the option of either going through the usual channels or expediting the process through a fixer or other under-the-table means. SOMBA’s role, he says, is to inform and advise the students. The underlying assumption is that the students have been taught the right thing in their previous subjects, know the right thing, and can apply it when the time comes.

In reality, Lagdameo notes, business ethics sometimes falls into a gray area, a balancing act between good business practice and practicality. Continuing with the example of a student registering a business, he outlines, “It’s going to be unethical for us to tell a student, ‘sige, mag under the table ka,’ but it also follows it’s not fair for us – it’s unethical for us – to say, ‘go and do the normal way,’ knowing for a fact that it might take him three months and he will not get anything done versus if you go under the table and get it done in a week’s time. Our ethical role here is to say ‘there is this option, there is this option, and you have this option. I hope and pray you guys make the right decision.’”

Beyond profits

At the end of the day, businesses are essentially being restricted into compliance by way of fines and other regulations. It provides a way of controlling the negative effects brought about by businesses’ apparent self-interest, but also brings to light the issue: If such ethical standards have become necessary, does it mean that business ethics and profit maximization are naturally at odds with each other?

More modern capitalist thinking suggests that business ethics and profit maximization are not at odds with each other, but are in fact integral. Chasing profit is still very much a part the business, but rather than pursuing it with methods that marginalize its stakeholders, the business is able to maximize profits by alleviating the conditions of the communities it is involved in.

The importance of this fact lies in the mutual point of agreement between businesses and the needs of the people, especially the marginalized. In The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, C.K. Prahalad and Stuart L. Hart argued that the poorer income brackets are an opportunity for businesses to make money and help the poor at the same time. By providing access to products and services that satisfy the needs of people in the marginalized sectors, businesses are able to profit in an untapped market and address problems of the poor in the process.

In this sense, profits become the measure of whether or not an enterprise is creating value for society through its customers. Doing good business involves doing business with a social mission and profits can serve as an indicator of how much value it has generated to society. As Lagdameo says, “It’s not just about money, it’s also output with environment, sustainability, [and] communities at the bottom line.” He further emphasizes, “The common good is also part and parcel of the whole process.”

This brings forth the ethical purpose of doing a business. Beyond making profits, businesses are able to generate sustainable income for its employees and provide the needed products and services to sectors that need them the most.

Doing good business

Indeed, following ethical regulations – paying taxes, mandatory benefits, or investing in better facilities – is often taken for granted because it presents itself as additional expenses in the part of the business owner. It is not surprising then, that even students who are under constant supervision by school authorities try to circumvent these policies in favor of higher profits.

In order to temper the efforts to circumvent proper business practice that compromise the social aspect of business, the Ateneo must find a way to further integrate business ethics in its curriculum not only in the form of compliance but also in conceptualizing business models that serve a marginalized market. In this way, the formation of being a person-for-others is integrated in the process of pursuing profits.

Of course, it goes without saying that in doing good business, an organization must profit well within the boundaries set by the rules of the game. Whether or not the law and other ordinances are necessary is another matter. The law may be harsh or inconvenient, but it is the law. As persons-for-others, the least we can do is comply.

What do you think about this story? Send your comments and suggestions here: tgdn.co/2ZqqodZ