Determining the amount of money to pay employees requires the balance of a number of conflicting factors. On one hand, compensation is the desired end. On the other, the institution’s financial sustainability is still a priority.

In the Ateneo, the Office of Human Resources Management and Organization Development (OHRMOD) determines how much employees are paid and what benefits they get. They have structural models to ensure fairness in distribution, but in spite of this, computations hint at unfairness, according to the Ateneo Employees’ and Workers’ Union (AEWU).

How much an employee is paid dictates how much an employee can afford, and this directly plays a hand in the quality of his or her life. Because of this, the union suggests more transparency on the part of the OHRMOD. They pose a question: How exactly does the office determine how much an employee gets paid?

Competition

The scope of the office extends to all employees of the Ateneo: Full-time, project-based, and labor union members. Ma. Victoria Cortez, director of OHRMOD, states that the university uses its wages structure to comply with government-mandated circulars or wage orders. She also says that the school gives additional benefits beyond government-mandated ones, such as Pagtutulungan sa Kinabukasan: Ikaw, Bangko, Industriya at Gobyerno (better known as Pag-ibig) and Social Security Service remittances.

“We have a structure—a salary structure, I mean—for the regular employees or the permanent employees. There is more variation for project employees because they are paid differently. Most of the time, for project employees, they are paid based on their deliverables,” Cortez says.

When it comes to benefits, the Ateneo is generous when it comes to education. The Ateneo employees have access to scholarships with up to a 50% discount in tuition and the rest can be paid on installment from their salaries. The children of permanent employees in the university get a 65% discount on their tuitions.

Cortez states that the main way to determine wage is to put a price on the jobs themselves. The starting salary will correspond to the qualifications of the person being hired. For example, aspirants with more experience and higher educational attainment will have higher starting salaries than those with less experience and lower educational attainment. She points out that other concerns, such as promotions in rank, are not determined by OHRMOD, but rather by an independent committee, the Committee on Faculty Rank and Permanent Appointment.

OHRMOD also computes and updates the employees’ standard wages every three to four years to check if they are still at par with the wages that other universities offer their employees.

“For the updating [of wages], the [office’s] practice is to join salary surveys, to do checking with the comparable organizations in the industry and see where you are positioned as a player in that industry. So, we can check with our competitors and see if our pay is competitive enough, but that should also depend on whether the university wants to take the lead on paying high or [if it wants] to be a second player,” Cortez says. “It depends on the strategy of the university.”

Meritocracy

Besides keeping wages competitive, another responsibility that the OHRMOD has is negotiating with the AEWU. The Philippine government mandates that a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) should be proposed every five years, with renegotiation on the economic provisions every third year. Cortez says that the common practice is for the union to present a proposal, which will be met with an offer of a counterproposal from the OHRMOD. Negotiations will take place until both parties are willing to sign a contract.

The meat of negotiations is the salary increases. The Ateneo offers two kinds of increases: The general increase, which accumulates based on the number of years an employee works in the Ateneo, and the merit increase, which is based on the performance the employee delivers during the year.

AEWU President Sonny Amata not only thinks there might be a propensity for people to take advantage of the merit system, but he has also observed it. He explains the merit system as performance-based, but the ratings come from a supervisor who is not a member of the union—this means that he or she may not be the best authority on the merit of their work. Also, the fact that people are judging how hard someone works usually means that there is a chance for bias to affect the supervisor’s decisions.

A possible effect of the merit increases may also be a cut back in the general increase that other employees receive. In this case, meritocracy, often useful to create equal playing fields, does not reap benefits for those whose merit is not recognized. While there may be nothing wrong with meritocracy itself, that there is a chance some employees will be denied of just compensation is something that cannot be avoided. According to Amata, the loss of income that may significantly affect how some of the employees live is the heaviest burden, because it is no rare occurrence that some employees can get a 0% merit increase.

During the CBA negotiations, Amata says that a lot of time is spent discussing the general and merit increases. He has been an officer of the union for 18 years and has regularly attended the CBA negotiations. “Sa tuwing nakikipag-negotiate kami, noong unang-una pa, nakaranasan ko nakakakuha kami ng magandang increases sa benepisyo at tsaka sa suweldo. Lately, noong nagkaroon ng pagbagsak ang ekonomiya ng Pilipinas, natamaan din kami (When we negotiate with the office, in the beginning, I experienced getting significant increases in benefits and in wage also. Lately, when the economy of the Philippines declined, the union was also affected),” he says.

In light of the recession and the subsequent lessening of the annual increase in school tuition fees, the salary increases have also lessened. This is because of Commission on Higher Education Memorandum Order No. 13, which states that 70% of tuition increases is for the payment of salaries and wages of the employees. Additionally, the AEWU has concerns that the entirety of the 70% is not being utilized.

“During my early days here in Ateneo… we had 10% general increase and a maximum of 10% also for the merit increase,” Amata says in a mix of English and Filipino. The increases have been decreasing since then and are now at only three percent.

Amata makes it clear that, compared to a lot of places, the Ateneo still has a lot of benefits that many companies do not offer. The school is able to give compensation that he finds is very helpful.

Part of the difficulty in this meritocratic scheme of determining wage is cultural. Amata agrees that there are still undertones of prejudice in the country. He feels that the Ateneo is one of the places that try to foster a fair and equal view of each person—with efforts coming particularly from the priests—but he concedes that in corporate or more private settings, the notion that maintenance men and other laborers are lesser people still somehow persists. This is especially troublesome because many of the supervisors and the people from offices that the laborers interact with come from the corporate world.

“Sa Pilipinas, hindi nawawala ‘yong style ng pagiging alipin ng mga mahihirap… Parang natatangay pa rin nila ‘yong kanilang pagiging dominante (In the Philippines, the style of treating the poor as slaves hasn’t disappeared. It is like the rich inevitably become dominant),” he says.

Comparison and transparency

Former AEWU President Tobias Tano now oversees the All Filipino Workers Confederation, which AEWU is a member of. He thinks what is really needed now is more transparency coming from the OHRMOD and the way the office does their computations for the wage increases.

To cross-check, the union does their own computations for the wages. They were provided with the following information: Non-union employees have up to a 6% increase, while union members have only a 3% increase maximum. The merit increases for non-union members should be double that of union members, then. Using the data they were given, the union computed that a 5.5% increase for a non-union employee would be a 2.5% increase for a union member, a 5% increase would make for a 1% increase, a 4% is a 0.75%, and 3% is a 0.50%, and anything lower than that was a 0% increase for union workers.

Amata calls it a “twist,” because on paper, the definitions are clear, but the exact computation does not add up. This system began in 2004 when Imelda Nibungco was the director of OHRMOD, and until now, the office has not released a full explanation for why this is how they execute this system.

According to Cortez, other schools, such as De La Salle University, publish their starting salaries online, but this is not something that the Ateneo would do because salaries are “a controversial issue for most people, not only in universities.” She believes that it is to avoid a tendency to compare, especially since salaries are “a confidential thing.”

However, Tano believes that publishing salaries online will fulfill OHRMOD’s goal to be more competitive. Those who want higher pay will also look for places with higher starting rates.

But even without having the salaries published, employees can still find out how other similar institutions are compensating their employees. They converse with members and presidents of other unions. For instance, Tano says that the starting salary in the University of Santo Tomas is higher than that of the Ateneo. They know that in Far East University, the tuition increase is much less than that of the Ateneo but the increase in salaries is much greater than here. This was actually the justification that the union had during the deadlock in negations last December.

Making ends meet

What is clear from past meetings is that the union wants the OHRMOD to be more transparent. The general sentiment is that working full-time in the Ateneo is better than working in a lot of places. However, salaries and wages can never be divorced from practical aspects of day-to-day living.

During the deliberation for salaries, Cortez points out that the office adjusts to the inflation rate. Because of workers find it difficult to cope with the continually decreasing increases in salary, Tano believes that the OHRMOD should consider other factors besides inflation, like how like the power of the peso and the interest accrued on a debt.

“ Yong aming mga suweldo, naiuutang namin bago pa namin matatanggap (We use our salaries for our debts before we even receive them),” Amata says.

More than anything, the union workers desire stability. The entire purpose of the union and negotiations is to educate other employees on their own rights and responsibilities. Outside the negotiations, the OHRMOD and union maintain industrial peace. It is far from the common picture of workers on strike against the administration, while both sides make unreasonable demands.

At the end of the day, people like Tano believe a lot of people work in the Ateneo because they enjoy it. What they would really want is to be placed on equal footing with the office, and to be respected enough to know what goes on in determining a part of their livelihoods.

The Price of Labor

By Alex A. Bichara and Mivan V. Ong

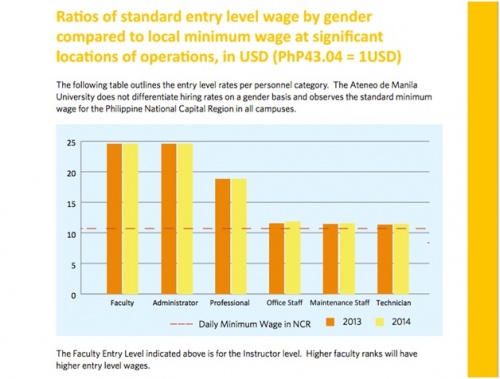

According to the Ateneo de Manila University Sustainability Report released in July 2014, the Ateneo pays at least the minimum daily wage to all of its employees, regardless of position or gender. The amounts that Ateneo employees earn, however, vary according to their position in the university.

As such, high-ranking personnel have higher daily salaries than low-ranking personnel. For teachers, newly hired instructors adhere to the faculty entry-level wage. Teachers who ascend in faculty rank have their wages increased accordingly.

What do you think about this story? Send your comments and suggestions here: tgdn.co/2ZqqodZ