Perhaps discrimination based on age is not on the list of social issues that one may readily declare present in the Loyola Schools (LS).

A student will experience having an elderly professor at least once—most probably for a philosophy or theology class. A student may also experience being taught by a teacher who is a fresh university graduate. Ageism is just not intuitive in the LS.

But unknown to many, ageism does exist on campus—it is present and institutionalized, made actual in the faculty manual. It affects the very people who shape the minds of the students: The teachers.

Retirement policy

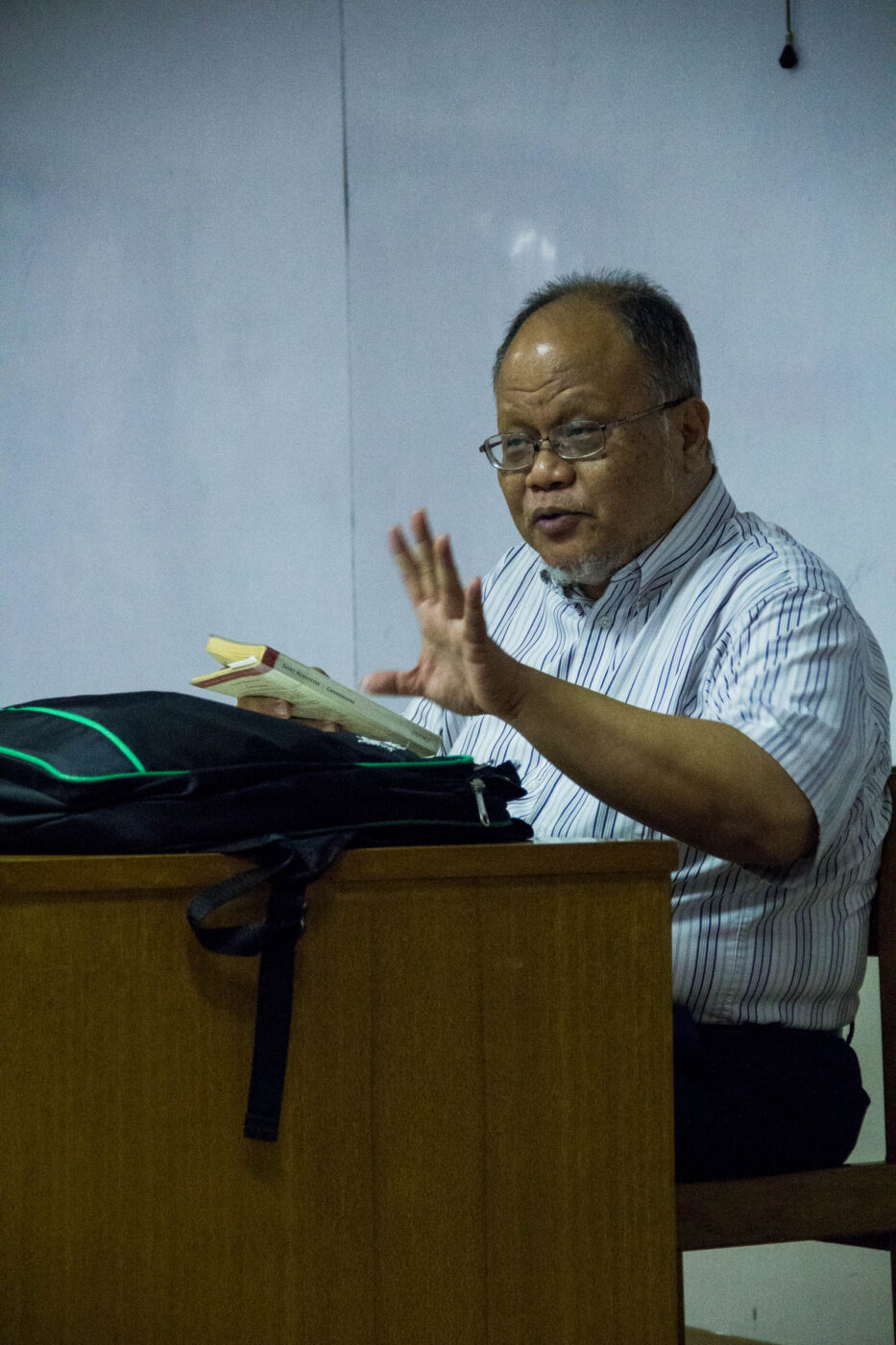

In his Inquirer opinion piece entitled “Still teaching 24/7” dated June 28, 2014, Manuel Dy, Jr., PhD, a professor from the Philosophy Department, opens: “I never thought ageism—defined as ‘prejudice or discrimination against a particular age group, especially the elderly’—would hit me.”

It was in the LS when ageism hit Dy, and it took the form of the retirement policy. Because the faculty manual is not available to students, Dy, Associate Professor Leovino Garcia, PhD of the Philosophy Department and Vice President for the Loyola Schools (VP LS) John Paul Vergara, PhD, relayed this policy to The GUIDON anecdotally.

At 60 years old, professors are given their retirement pay. They can also get rehired twice. The first time, their contracts last three years. The next time, two years. At that point, the professor would be 65 years old. Should they get rehired, it is then when their teaching loads—and their salaries—drop, from 30 units to 15 units, and their titles are changed from full-time professor to part-time professor.

Dy says that the faculty manual is actually “silent” about what happens after a professor turns 65 years old. In 2002, the then-vice president of the LS, Anna Miren Gonzalez-Intal, PhD, issued a memorandum about it, but until last year, the policy was not put into writing in the faculty manual. Dy even says that he was informed of this policy only verbally.

Garcia, on the other hand, was not personally informed about the policy. He shares that he received an email during the break between the first and second semesters. It was through the email that he was told that he could only teach full-time with a prorated half-load. He was already 67 years old then.

He details the systematic procedure he followed: Requesting two rounds of appointments and talking with School of Humanities Dean Maria Luz Vilches, PhD, VP LS Vergara, and University President Jose Ramon Villarin, SJ. Additionally, Garcia wrote letters addressed to Villarin, to Chairman of the Board of Trustees Edward Go, and to the other members of the Board. According to Garcia, these letters were never answered in writing. However, he received a reply from Vergara immediately after he read Dy’s Inquirer article.

Vergara says that, on the administration level, this policy—giving 65-year-old professors half-time load—forces department chairs to start thinking about intergenerational balance in their departments.

Vergara emphasizes that the policy by no means prohibits 65-year-old professors from teaching a full load. He emphasizes that they ultimately leave the decision to the departments.

“If there’s a need [to retain a 65-year-old professor’s full-time load], then the department just goes to us and says, ‘We need him [or her] still,’ then we can deal with that,” he says. “This policy is actually subsumed under the fact that, in the end, it’s the department, the requirements of the department or the balance that the chair has to deal with that come into play [when deciding whether or not to retain a professor’s full-time load].”

Vergara is hesitant to conclude that the policy is ageist, because then that would mean that “the whole concept of retirement is ageist. He also adds that ageism can may even affect the younger faculty members. He says, “For example, if you say, ‘Let’s not bring in new faculty or younger faculty’—that’s also ageist.”

A balancing act

Because the policy affects the teachers of the LS, it is easy to see how the LS would be affected by the policy.

For Dy, the problem of this is that it deprives students of the opportunity of being taught by more experienced professors.

In addition, Dy also warns that this policy could have negative effects on the Ateneo’s education quality, particularly when applying for centers of excellence. According to Dy, accrediting institutions such as the Philippine Accrediting Association of Schools, Colleges and Universities, and the Commission on Higher Education, look at the number of doctorate degree holders there are in the faculty—and, of course, the higher the educational attainment, the older someone is.

When talking about the faculty in general, Garcia and Dy also stress the need to keep university tradition and memory alive through the faculty, especially senior faculty. Both professors see the faculty as the university’s means of passing tradition. “They’re the continuity of the university, so if you remove them, there’s no more tradition to speak of,” says Dy.

For all its negative effects, Dy and Garcia can only speculate about why this policy was suddenly implemented in the first place. The first reason seems to be cost-cutting. Two other reasons betray prejudice against the senior faculty: That they hinder the promotion of younger faculty, and that senior faculty “decline” in their teaching.

Despite the controversy that it is causing, the LS retirement policy, like all policies, would not have been implemented if it the administration did not deem it necessary. Vergara cites two main reasons in defense of the implementation of this policy: An overall intergenerational balance in the faculty and the cutting of costs.

The intergenerational balance that he talks of is the just proportional presence of senior and junior faculty members. He says that the fact that younger professors outnumber the senior professors is an “expected curve.” A faculty composed mostly of senior professors, he says, is not sustainable.

Vergara also mentions the need for turnover between younger and older faculty members. The turnover serves as a passing of the torch from older to the incoming faculty members. This marks the passing of tradition. According to him, if there is no turnover, then, there would be no continuity. Worrying about the future, he also says that a senior professor cannot teach the same subject forever, so it would be better to start training a new or younger professor while the senior professor is still around to help.

Besides the need for intergenerational balance, finance was also a contributing factor in the implementation of this policy, because “the more senior you are, the more expensive you get.” The solution of the policy is simple: When professors hit 65, their salaries are cut in half. Dy also notes that, should the professor take on overload work—18 units, for example—that payment for that only comes later in the year.

Despite its restrictions on the senior faculty, Vergara defends that the policy has room to accommodate the specific needs of the professors, although the option to rehire professors rests in the hands of the department chair. “I think, partly, our retirement policies allow it, allow that flexibility. The way we do things in Ateneo allows consultation,” he says.

Vergara does not think the policy should be reviewed or amended precisely because of this. “I don’t think [the policy] requires any kind of amending because it provides the option [for 65-year-old professors to continue teaching full-time]. It doesn’t limit, really. It gives us some bounds,” he says.

The fight

Garcia emphasizes that he has moved on. But he cannot deny that he is simply “disappointed” that he has been “shabbily” treated by some administrators of the institution that he feels he has loyally served for almost forty years. He stresses that he is not fighting for what has happened to him; he is concerned how the policy will affect the younger faculty. He hopes we are not moving towards a “corporatization of the university.”

Similarly, Dy also has the future generations in mind. He says, “I actually wrote that letter to the Board precisely to make them think about it, rethink the policy because I was not writing it for myself alone.”

Dy also says that explicitly discouraging 65-year-old professors to teach full-time because of their age—because of something they have no control over—violates one of the driving principles of the Ateneo community. “It’s not—to my mind—in accordance with our Jesuit characteristic of magis—more,” he says. Garcia says that senior professors would also want to teach in the LS longer to give back to the school.

For Garcia, how the policy is carried out is one of the more hurtful things about the policy. He recalls that he was told the news—that he would not return to teach a full load of 30 units, that he would teach half of the classes that he regularly teaches—came on the glimmer of a computer screen instead of in person. He says that emailing teachers that they could no longer teach is inhumane.

Both Dy and Garcia wish that the administration treated the faculty better. “Your faculty is your gem, is your treasure, so you should treat them well,” says Dy. He says that it is teachers who shape the minds of the students, and it is the students who make the school.

Garcia points that in a university setting, experience is gold. He notes that some subjects, especially philosophy, require long years of experience in order to be taught well.

He likens some teachers to wine—they only get better with age.

Updated: Jan. 24, 2015, 10:22 PM