Janet Lim Napoles has gone from rubbing elbows with the country’s powerful politicians to acquiring notoriety overnight.

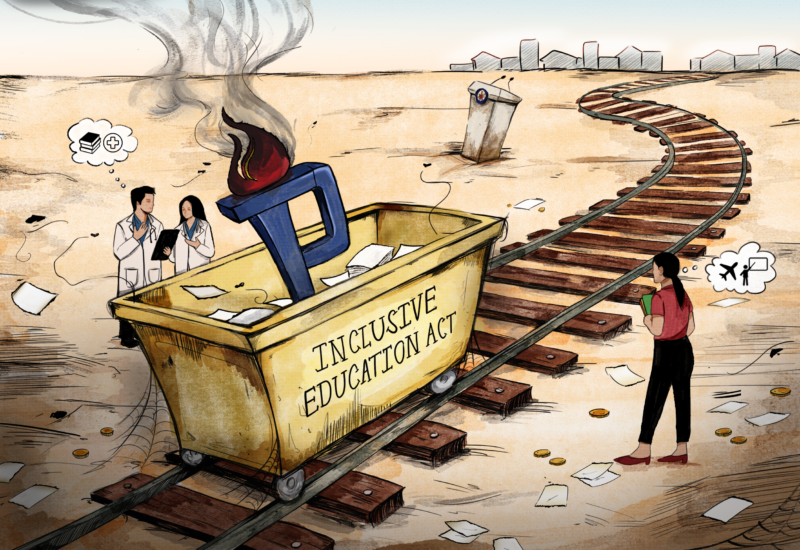

Last July, Napoles was accused of taking P10 billion from the Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) or pork barrels of various congressmen and senators for her family’s personal use.

Her business empire, JLN Corporation, has been linked to several fake non-government organizations (NGO). These NGOs were allegedly used to transfer the stolen pork barrel funds to various lawmakers and JLN’s incorporators by way of ghost projects.

As scandalous as Napoles’ situation is, though, the PDAF has always been used and abused. Created in the 1930s according to the General Appropriations Act, the PDAF is an annual allocation for legislators to subsidize local development programs.

In theory, the PDAF is a good idea. The country’s legislators distribute the pork barrels to fund projects such as the construction of roads and the development of public schools. Because the central government can’t oversee each and every district, a fund for isolated, local development is practical.

However, history has proven the system to be greatly flawed. While measures are in place to keep PDAF spending in check, these are circumvented often and easily.

In most pork barrel scams like Napoles’, the materials and labor needed for the project never appear or are only partially delivered. The money for the rest of the project is then distributed among the legislators, local officials, contractors and other individuals involved.

The only tenable solution, it seems, is the abolition of the PDAF. Funds can thus be centralized at the level of national departments. Corruption is undoubtedly still present at this level, but accountability will be more easily established.

The greatest obstacle to such a system, however, is that the Senate and the House of Representatives pass the annual budget and would not, by any means, approve a budget that deprived them of their pork.

Whether or not legislators use their PDAF scrupulously, removing their funds will weaken these legislators’ padrino relationships with their constituents. If congressmen can’t provide immediately tangible projects for their districts, what do they run on come the next election?

The answer is their track records, precisely, as legislators.

The abolition of the PDAF will require a significant culture change—one that moves from systems of patronage to responsible use of government funds. Furthermore, without the PDAF, congressmen and senators can focus on the task of actual legislation. On their part, citizens can begin to elect legislators, rather than godfathers, into office.

Senator Miriam Defensor-Santiago has proposed the gradual abolition of pork, which could be more amenable to legislators and would be instrumental to bringing about that culture change.

The question remains, however, whether other senators and congressmen will agree to kick-start the gradual death of a system that’s made them so much richer at the expense of the constituents they serve.

A contingent from Ateneo is marching on Monday, August 24, to support the abolition of the PDAF. Click here for more information.