When I was asked to write this opinion piece about intellectual property rights (IPR) in the visual and graphic arts, I immediately agreed. But as I set upon writing it, I realized that I know very little about the nitty-gritty of IPR laws in the Philippines, or if we have implemented this law in the visual arts at all.

I am aware that the Ateneo has some very strict policies regarding academic plagiarism, so I try to implement this policy when it comes to my information design students’ projects as well. The rubrics of graphic design grading lack the specificity of grading language-based work, so I admit that it’s very difficult to judge a piece as a plagiarized one. But as a teacher who grades logos, magazine layouts and posters for a living, I have to manage.

Many designers and artists from all over the world have intensively discussed the issue of plagiarizing design work. Steve Jobs once quoted these much-misinterpreted words of Picasso: “Good artists copy, great artists steal,” while renowned illustrator and typographer Jessica Hische reasoned out, “Just because it’s not illegal doesn’t mean it’s ethical.”

I know of people who have had misunderstandings and ruined friendships over “stolen” styles and identities. It is normal for visual artists to be heavily influenced by particular people; everyone has their own personal tastes. But it remains difficult to draw borders on plagiarism in the visual arts. Does a piece have to be a 100% duplicate of another work? How many elements and principles of design have been copied? How similar are the typefaces and photos used? Does one get a certain feeling of intuition when he senses a plagiarized work? The list goes on.

The first time I’ve ever placed a registered mark on a design work was a brief website-making stint when I was 13 years old (the Internet was still a small place back then). It was a tight community of designers and friends who closely monitored each other for plagiarism and copying. The rules were unsaid and unwritten but very binding: Designers who copied the look and feel of another website without credit were subjected to public shaming by means of a very heated blog post. Web designers who lifted blocks of HTML code from another website would have their site comments section bombarded with disapproving notes.

We were a bunch of teenagers babbling on about copyright and trademarks in graphic design but we probably didn’t know exactly what were we talking about. We were probably also violating some other kind of property law because we were using trademarked images from various media companies. But one thing was clear: Copying was bad.

It was a good baptism of fire for us, as we learned to mark and place credit on every source we took from. But as we went on with our design process, we realized the existence of design trends that permeated the work of the community. That is where the difficulty sets in. When a design trend influences much of a community’s work, how can you distinguish the copies from the originals? Why is it okay to follow a design trend but wrong to copy a certain work?

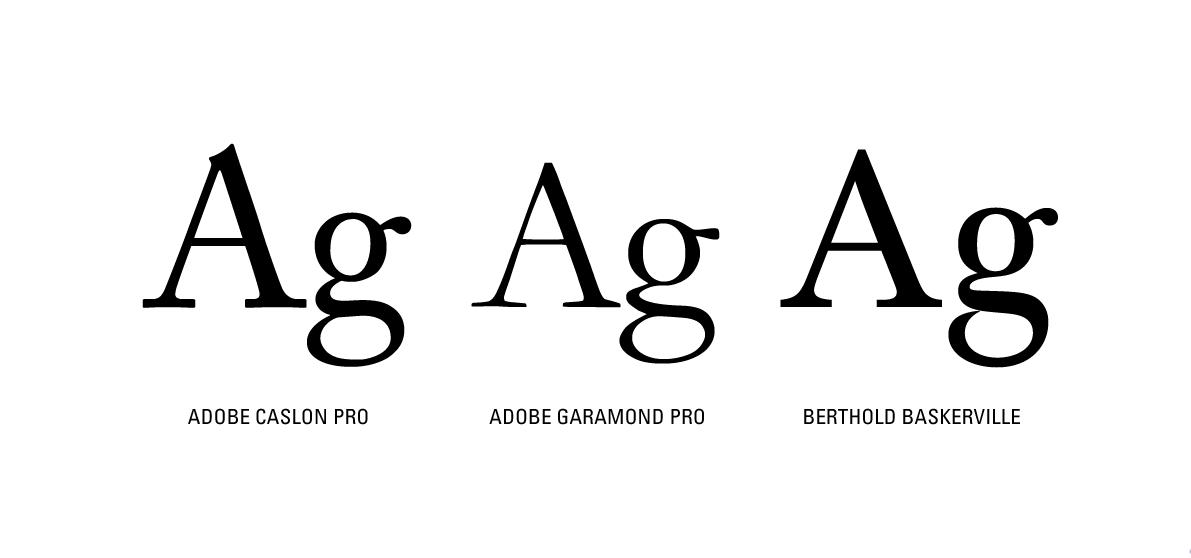

In Europe, typography in the 15th to 17th centuries looked essentially the same but we know for sure that John Baskerville didn’t plagiarize from William Caslon or Claude Garamond. Today, Apple software engineers have embraced the dominance of flat user interface design to follow the aesthetics started by Microsoft and Android. Designers are never separate from the world they inhabit; part of every designer’s journey is the learning experience of referencing from the richness of their community.

A good way of using a design trend is when a personal style and experience is contextualized & infused with the collective aesthetic of a community’s current style. Plagiarism in design, however, bypasses a sense of the personal and assumes the role of another existing work.

When people talk about plagiarism in design, the focus is usually on the one being copied from, but I’ll try to center on the one doing the copying instead. In a field of study where a lot of ego is involved, the plagiarizer usually has more to lose.

My personal design philosophy is that we design based on our own personal experiences: The movies we watch, the books we read, our favorite colors as children, our feelings of anguish when our readings have too small a font size, every road violation we’ve made on account of poor signage. To copy one specific work is to bypass one’s own identity and assume the experience and feelings of another person. That said, surely a personal design style deserves more than just a browsing of some portfolio website, getting inspired and then assuming a very similar aesthetic. That would be like reaching the summit of a mountain without ever making the hike.

Despite my musings on plagiarism as a shortchanging of a personal design identity, the truth is that it’s very difficult to control or think about intellectual property rights in a field of work where the deadlines are short and the clients are often stubborn. Honestly, the best thing we can do as designers is maintain vigilance, constantly put out great work that exceeds our previous pieces and respect the peers in our community.

After all, graphic design never really killed anyone, right? Right?

Tata Yap is a part-time lecturer for the Fine Arts Program. She graduated in 2011 but still feels awkward walking through SEC Walk.