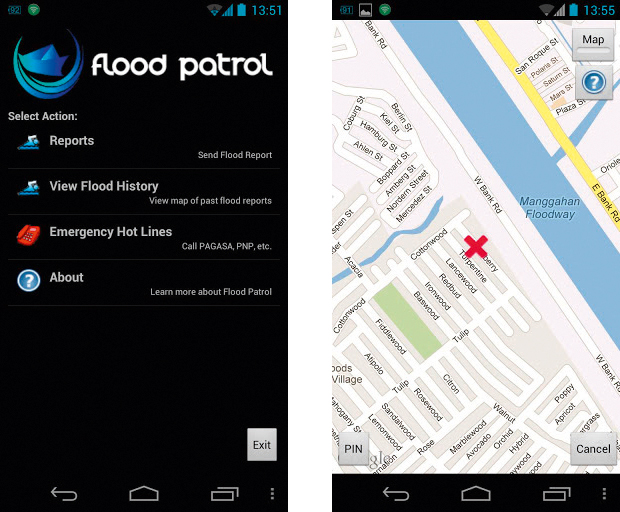

FLOOD MONITORING. The new mobile application lets users send data regarding flood conditions of a certain area. Photos of the area can also be submitted alongside additional descriptions. Photo from Google Play.

THE ATENEO Java Wireless Competency Center (AJWCC), one of the research centers of the Department of Information Systems and Computer Science, has developed a flood monitoring and reporting mobile application.

Called Flood Patrol, the application was made for Android devices with a camera, wireless fidelity (Wi-Fi) and Global Positioning System (GPS), with the Samsung Galaxy Y being the most basic phone tested to run the application.

Along with the mobile application of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST)’s Project Noah (Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards) website, Flood Patrol was launched on October 17.

When a southwest monsoon hit the country in August, AJWCC Executive Director Reena Estuar, PhD pitched Flood Patrol to Mahar Lagmay, PhD, the head of Project Noah.

“What we did was unusual. I got in touch with Mahar… and then we developed it without contracts, but with the blessing of VPLS [the Vice President for the Loyola Schools] and the [School of Science and Engineering] dean,” she said.

However, the project was not funded and no one got paid for it. Estuar volunteered for it because the application would benefit the public and did not consume a lot of resources to develop.

“I knew that I was bringing honor to the school and that it felt right. It was right in all aspects: in terms of research, in terms of public service, in terms of… mobile applications development.”

Currently available on Google Play for free, Flood Patrol was developed by Estuar, project manager Christine Amarra and head software engineer Jeffrey Jongko. Graduate student Mark Fajarda worked on the module arrangement and icon design.

As of press time, Flood Patrol has over a thousand downloads. In the works are versions for other mobile operating systems such as iOS, Windows Phone and Symbian.

Using Flood Patrol

Project Noah, through its eight component projects, aims to use science and technology to help the government in disaster prevention and mitigation.

Flood Patrol, patterned after the Philippine Flood Hazard Maps, uses crowdsourcing of data for disaster management.

It accomplishes this by allowing users to report and monitor flooded areas. Users may call or send a text message to emergency hotlines. Sending a report requires information such as the date, time and flood location.

Flood location can be determined using GPS, or users can type it in so they can choose the exact area. The flooded area will then be marked with an “X” on Google Maps.

Photos can be attached in the report for verification. Users must also determine the flood height, with the options of “no flood,” “ankle-high,” “knee-high” or “waist-high.” Additional details may be included and the application will ask for confirmation before the report is sent.

In viewing flood reports, affected areas are marked with colored dots, each corresponding to a certain flood height. Results can be filtered down.

Reports go to AJWCC’s servers, which is accessible to DOST. The received information will, in turn, appear on the DOST website.

Empowering the community

Flood Patrol can also benefit local government units (LGUs).

Estuar said in an email, “For LGUs, they can monitor flood reports in their areas, in real time. They can do verification via the web because the images are viewable in a secured site.”

Amarra said that the application could raise awareness and help LGUs prioritize the areas that need relief aid or evacuation.

“If the LGUs know that this part [of their area] always floods, maybe it’s something they could look into already: what causes the flood?” she said. “Is it something that they can address? Like, is it because of a clogged drainage, or is it really because of [the] location, because you’re just way below water level or this [area] is where the river overflows into?”

For Jongko, the application is more of a guide for regular users on which areas to avoid. However, he added, “It will make them feel more that they’re involved in something bigger, that they can help out.”

Crossing fingers

Communication juniors Benise Balaoing and Karis Corpus both said the idea for the application was “great.” They were both affected by Typhoon Ondoy, which lashed the country in 2009.

“It’ll help in determining whether my relatives are safe or not—most probably, at least,” Corpus said in an email interview. She is crossing her fingers that the application will always work well when needed.

“Hopefully, it won’t crash… when a lot of people are accessing it, or that it doesn’t depend on things that easily go down due to inclement weather,” she said, adding that Marikina City had no phone signal for a few days after Ondoy.

On the other hand, Balaoing hoped that Flood Patrol could guide the Ateneo administration in deciding class suspensions.

She also said that accessibility could be looked into more. “The people who live in low-lying areas who are in most need of the app don’t even have access to Android phones because they can’t afford it.”

Application development

Developing Flood Patrol did not take long, as AJWCC already had previous experience and in-house developed frameworks. Suiting it to DOST-Pagasa’s specifications took more time. Several other technical challenges were encountered.

Jongko said that it was the first time they utilized Google Maps in application development, so he had to find a way to seamlessly integrate it with their BlueBlade framework. Adjustments were made in light of camera technology advancements.

GPS issues were dealt with: how to make it work without crashing and how to locate the area if there are signal problems.

Other challenges included putting in place methods for the attachment of photos in the reports and the retrieval of flood reports and their visualization on the map.

The aim of making the application compatible with as many Android devices as possible also proved difficult, especially for low-end phones.

“We want to make sure it works for as far down as we can go, so that we can open up the application to as many people as possible,” Jongko said.

Originally, flood reports immediately go to the DOST website, but with the possibility of bogus reports and the misuse of photos, initial screening has been introduced.

“This is a government website; you don’t want people spamming weird stuff,” Jongko said.