NICOTINE FIX. Student smokers frequent the smoking area at the North Parking Lot. Photo by Abram P. Barrameda.

In what was once a university that allowed college students to smoke cigarettes inside its classrooms, the current policies of the Ateneo now enforce strict control over those who wish to have their nicotine fix. In fact, there are only two designated smoking areas in the Loyola Heights campus.

Technically speaking, smoking is banned in the premises of the Loyola Schools (LS). Republic Act 9211 forbids the smoking of cigarettes in educational institutions. The university’s smoking area, commonly referred to as the “smocket”—an amalgamation of the phrase smoker’s pocket garden—is situated in a student parking lot right outside what is strictly the LS (i.e., college) premises.

Beyond the stigma

Unlike issues that visibly involve a large and collective part of society, the phenomenon of smoking is often seen as one that is merely restricted to the personal and private life of an individual. In reality, though, social interaction is a key determinant of the make-up of any smoking culture.

For example, Atenean smokers maintain a unique social dynamic, which is especially manifest in the smockets. Cigarettes are treated as communal property; giving one away is only an issue if such is the last one in a pack. A conversation’s length can be determined by how many cigarettes are smoked and whoever stops smoking first. One can comfortably ask a stranger for a “light.”

Indeed, it is clear that, while sharing many things in common with their fellow Ateneans, student smokers of the LS maintain a communal character that distinguishes them from the rest of the student populace.

Starting the habit

Smokers have varying reasons for taking their first stick, and yet these somehow manage to culminate into forming the same habit.

Communications sophomore Guio Martinez points to the influence of family. “You come from a background where, you have parents who smoke, you have brothers and sisters who smoke [and] cousins who smoke. Eventually, you’ll be curious about it.”

RJ Dancel, a management junior, shares a similar story. “Actually, friends helped me get into [smoking]. Like, they paved the way for trying it. But my reason was my dad… I don’t know if it’s my personality, but I hated him smoking. So I wanted to try it just to hate him more.”

“He gave me the reason to hate it, but my friends gave me the privilege of doing it,” she adds in a mix of English and Filipino.

Media’s role

Although smoking seems to be influenced in a large part by familial and social circles, LS Guidance Counsellor Virgilio Panlasigui points to the role of media in getting people to smoke. “They target now the teens. They no longer target the adults. Why? [It’s] because the adults are already getting sick.”

Along that line, Jayeel Cornelio, PhD of the Sociology and Anthropology Department challenges the notion of media’s power to influence. “In public discourse, we tend to blame the television for a lot of our society’s ills, whether it’s promiscuity, overeating, or, in this case, smoking.”

Nevertheless, he is quick to point out the error in overemphasizing the role of media in the formation of smoking habits among the youth. “Although I will not deny the power of media to penetrate the psyche, let me challenge nevertheless the whole notion—it is not to be blamed entirely. In many cases, people learn the ropes of smoking not by watching TV or YouTube. Ask your smoking friends how they learned it and probably a lot will tell you that they learned it from their other friends when they were much younger.”

“I cannot emphasize enough the power of peers to shape behavior,” says Cornelio. “No adolescent would want to be excluded—unless you’re an avowed wallflower.”

Spaces and culture

When smoking comes to be seen not just as a relaxant but as a social device, the interactions around it beget distinct behaviors among smokers, so much so that some may even develop a culture centered on it. Depending on who is asked, this culture may be affected by the space in which smoking takes place.

“It’s a social lubricant. It makes people open up,” says Jake Jereza, a communications technology management junior, who likens the experience to travelling. “It would be the same as, [when] you’re in a different country, and people are speaking all sorts of languages. Suddenly you hear a familiar language that’s your own. It’s a group of people talking, a group of people from your country.”

Creative writing freshman Belle Mapa mentions how smokers are driven to the smocket for similar reasons. “I guess people just swarm there when they’re feeling stressed or when they just feel the need to kind of escape from school. It’s like we have our own little bubble in the parking lot.”

“In principle, anyone can smoke anywhere,” says Cornelio, challenging the suggestion that particular venues foment the development of cultures and habits. “But cultures develop around venues.”

Before the removal of most smockets on the university grounds, Cornelio recalls that certain areas in the Ateneo were known for different smoking cliques where people of a particular social character gathered. “The back side of the de la Costa Hall, for example, was popular among professors from SOH [School of Humanities].”

Cornelio further mentions that smockets are situated in an open area vulnerable to the elements of nature. What is notable for him is that, though smockets contain no roof to shelter individuals from sun and rain, these areas are still frequented by student smokers.

“But you see, even if [the smocket is] not really desirable, people still go there and they do talk. I have tried hanging out there a few times with some colleagues and students and it was interesting to see how cliques are formed—a ‘smocket cliques’ if you will,” he says. “Think about it: ‘Got a lighter?’ is a good pick-up line.”

Martinez, however, is hesitant with the notion of a culture specifically centered on smoking. “With regards to the smocket… I think what unites the people there is not really personalities, [because] there are lots of different personalities in the smocket. Rather, what brings them together is [just] the fact that they’re smoking.”

A hazy image

For many non-smokers, negative stereotypes are immediately attached to the image of anyone who smokes. “That’s what most of the world sees,” says Mapa. “That we’re… rebels or people with intense problems, but that’s not everybody.”

Smoking, strange as it seems, is alternately perceived as something both desirable and repulsive. According to Cornelio, the act of smoking can be associated with the siga archetype for males, which thrives on the eager demonstration of masculinity, and the chic archetype for females, which is a display of upper class femininity. Whether one perceives such labels to be positive or negative greatly varies among individuals.

Dancel alludes to the image depicted in commercials. “For stupid people, it’s like they idolize the character shown because he’s badass and he smokes. They think that they can do that in real life.”

“I guess it makes people feel adult, older, [as if they] know the world better,” says Jereza.

Cornelio dissects the image painted by smoking and identifies three forms of social standing that may be reflected in the very habit: aspirations of adulthood, economic class and cultural sophistication. “There seems to be some pride in demonstrating independence from parental oversight.”

“We can see that smoking in itself can be a form of distinction-making. To be able to access the ‘right,’ [usually expensive] cigarettes, one needs to see and know what others are smoking. It takes some economic ability to achieve that,” Cornelio says.

“Also, sophistication is seen in the accompanying behaviors. Does it not look ‘cultured’ to be talking with friends at a posh café with cigarette in one hand and coffee in the other?”

Consequence and habit

There still remains the question as to why smokers nevertheless continue their habit, despite their knowledge of the harm it does. It is very unlikely to find a smoker who is completely unaware of the health hazards that surround a cigarette.

According to Martinez, while an awareness of the risk may be there, its impact may not be significant. “I think the reason people still smoke even if they know these hazards is that, they feel that they’re the ones responsible for it, for their habit. So if ever they start feeling the side effects of smoking, they know for a fact that it was coming.”

Panlasigui returns to the point of how smokers interact with each other; he sees the act as a “common denominator” in terms of socializing.

“Sometimes, even if you’re not a smoker but you’re with people who smoke, you start with just puffing,” he explains in a mix of English and Filipino. “Then all of a sudden, the nicotine gets into your system already. You’re not just an associate. It’s you. Your body’s already looking for the nicotine.”

In relation to this, Cornelio says that it is the convergence of the social and biological aspects of smoking that form such a dependency. “By looking at the conditions of social standing that smoking affords an individual, we see smoking not just as an addictive behavior but also as a lifestyle,” he explains. “That smoking is both a biological form of addiction and an individual lifestyle makes it a very, very difficult habit to break.”

Change in perception

Perhaps debunking the perception of the smoker as someone shallow, unthinking and unsettling may help the non-smoker see smoking in a more holistic perspective.

Mapa asserts that a person is not made less of a person just because he or she smokes.

Meanwhile, Dancel says, “Some people think it’s a cool thing to do, but at the end of the day, only you can determine who you really are.”

For smokers who have let the habit comprise a large part of their identity, this could have in fact been borne out of a deep awareness of all its implications. After all, smokers probably wouldn’t be the last to know how a cigarette can shape or affect an individual’s identity.

Editor’s note: Interviewee Jake Jereza is part of The GUIDONs Multimedia Staff.

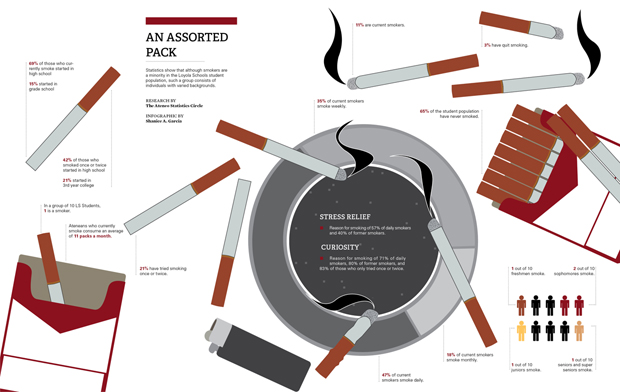

An assorted pack

Statistics show that although smokers are a minority in the Loyola Schools student population, such a group consists of individuals with varied backgrounds.