IN LINE with the University’s vision to be a melting pot of natural structures and urban wildlife, the Loyola Heights campus continues to evolve as a “living laboratory”—navigating the competing demands of biodiversity and a larger community.

During peak traffic hours, masses of private vehicles stifle campus movement along concrete roads that pass through the University’s green spaces, including the recently constructed e-jeep route along the School of Management Forest.

With an influx of student population brought about by recent policy changes and expanded course offerings—such as this year’s entry of BS Learning Science and Design students—there is an increasing need for infrastructure capable of supporting the campus’ various units.

Beyond the buildings

Amid increasing pressures of urbanization and modernization, the University has historically regarded itself to be committed to sustainability, striving to keep environmental stewardship at the heart of campus development.

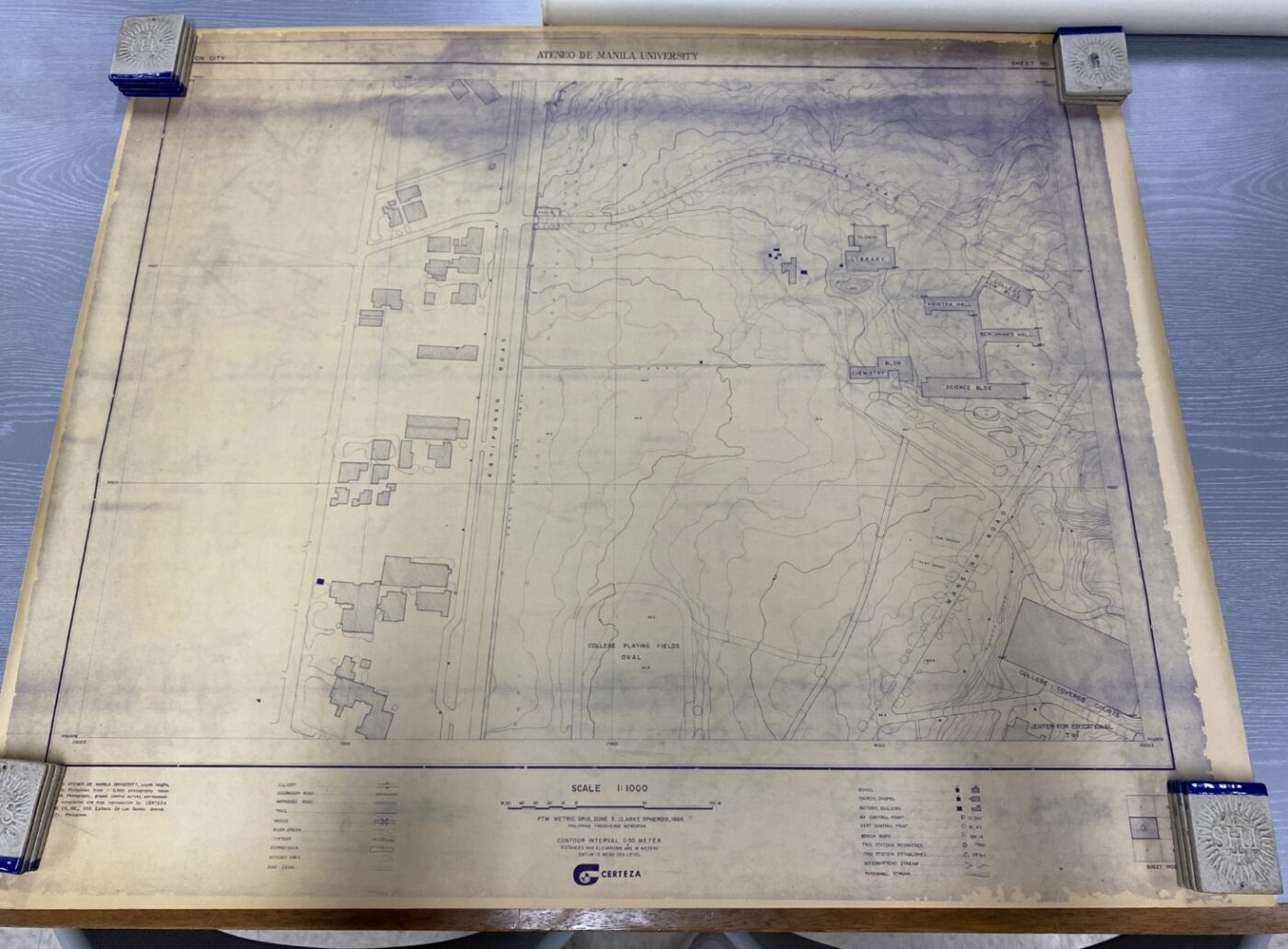

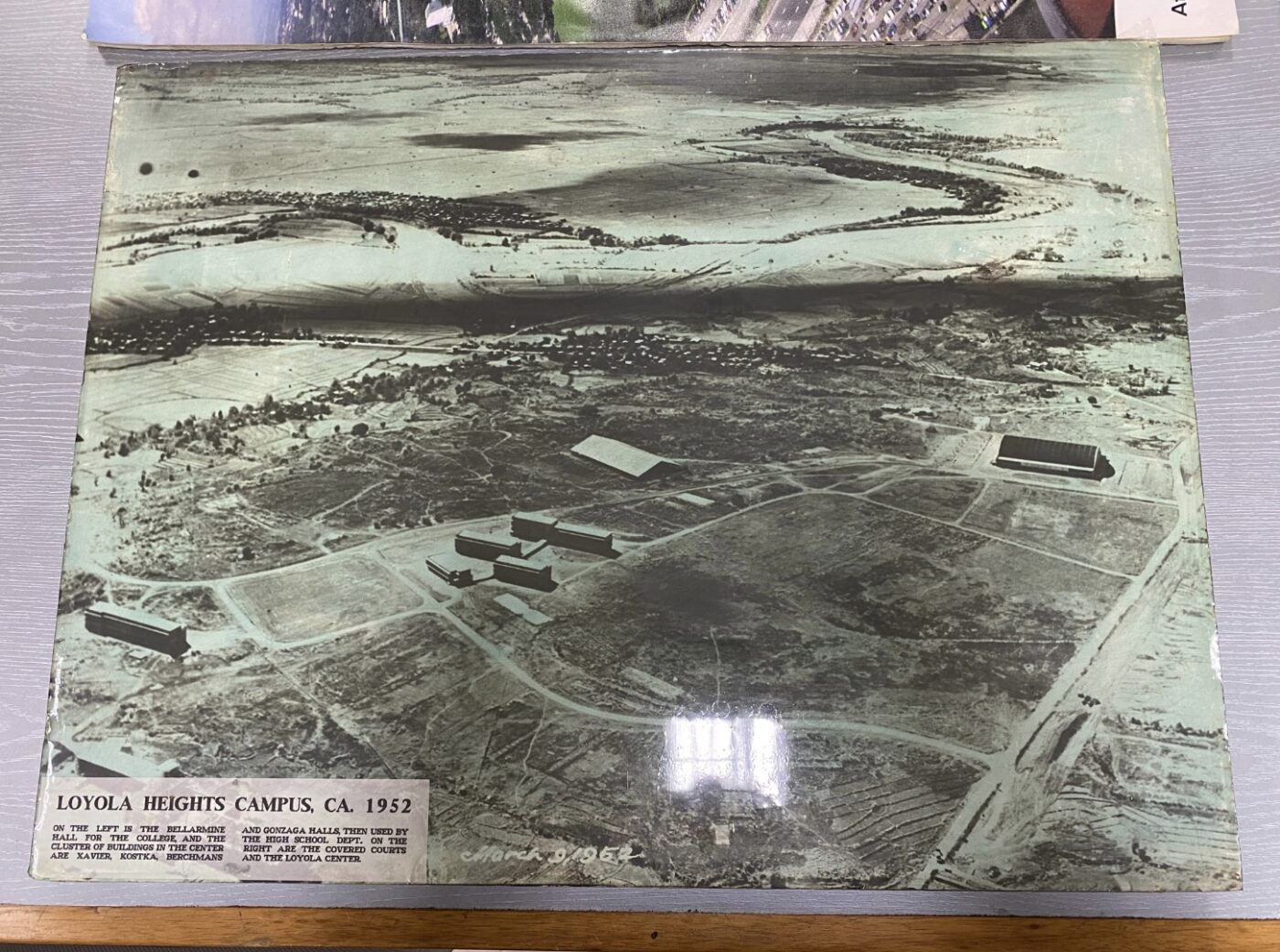

In 1952, the Loyola Heights campus was once an expanse of bare fields after its relocation from the Padre Faura Campus. These open lands stretched from the Blue Eagle Gym, the campus’ first building, toward Katipunan Avenue and the cliffs overlooking the Marikina Valley.

Former University President and Professor Emeritus Bienvenido Nebres, SJ shared that trees were planted across campus during the administration of Father William Francis Masterson to incorporate more greenery into what was originally a barren landscape. Within the same decade of this undertaking, however, these trees were uprooted during a strong typhoon.

The Ateneo campus also saw further infrastructural developments. The first buildings of the college campus—Berchman, Kostka, Xavier, and Gonzaga Halls—were constructed, with Gonzaga walls wrapping around an old Narra tree.

According to Central Facilities Management Office (CFMO) Director Architect Michael Canlas, campus structures are generally oriented from North to South to avoid natural heat, minimizing exposure to direct sunlight and acting as a natural cooling mechanism.

Conservation efforts to protect the locale’s original flora and fauna have also been made, which include the small forest by the Jesuit residences and the Gesù that has become home to all sorts of wildlife. “We preserved some kind of forest area for the University—like a lung, a part of [the campus] that breathes,” Nebres remarked.

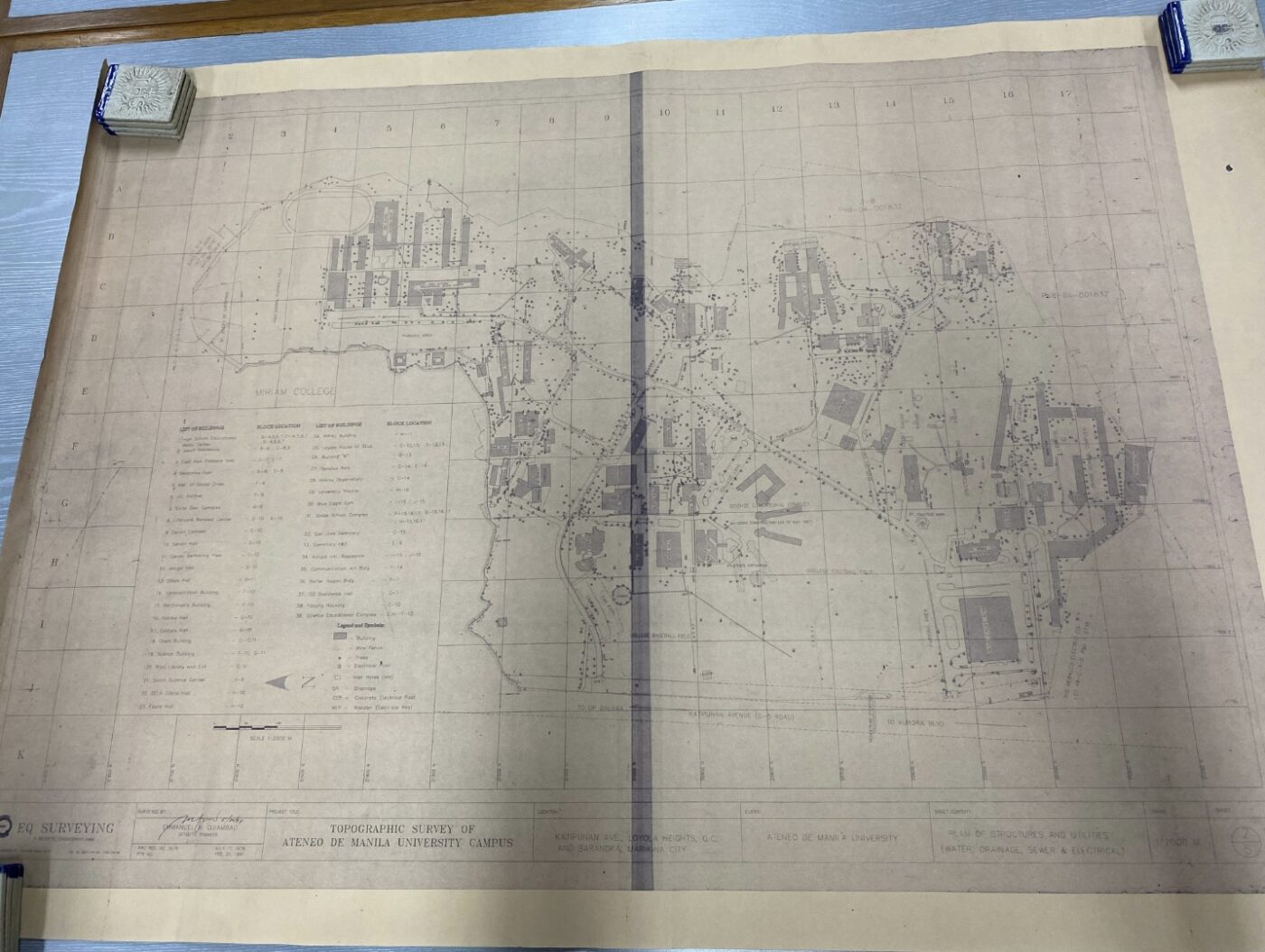

While building on this rich history, the campus also evolves to accommodate more concrete surfaces and structures, posing the challenge of harmonizing development with environmental sustainability.

Ateneo Institute of Sustainability (AIS) Director Emmanuel Delocado, PhD describes what it means for the campus to be a living laboratory. “A living laboratory must contain both the infrastructures, structures, and learning experiences as well as a culture of ecological education for a physical space to become a living laboratory,” he explains.

Since its institutionalization in 2013, AIS has launched various green programs as the University’s vehicle for sustainable development in collaboration with different campus units.

A notable example of such programs is the decentralized wastewater management system and the building wastewater management system under CFMO’s supervision, located behind the New Rizal Library, beneath the International Residence Hall, and by the Matteo Ricci Study Hall. Both systems mimic natural water treatment systems using aerobic and anaerobic reactors, ponds, and constructed reed beds.

Ecological education in practice

Aside from these projects, lesser-known initiatives also involve the maintenance of open fields—such as the Bellarmine Field, Ateneo Baseball Field, the major and minor Ocampo Fields, and Cervini Field—which all serve as evacuation sites in the event of a disaster.

Notably, smaller-scale sustainability efforts include the PLDT-Convergent Technologies Center and School of Management complex, which have installed decals on windows, acting as warning signals to birds to prevent surface collision and fatal injuries.

Campus trash cans are also designed intuitively to meet sustainability needs. Some of the dry paper trash bins have a slit-like opening for paper sheets, while recyclable bins have a round opening for polyethylene bottles and aluminum cans.

On a larger scale, campus construction follows existing sustainability guidelines that evolve with emerging technologies. For instance, new buildings must include a rainwater harvesting system that collects rainwater for plumbing, while roofs are intentionally designed to support solar panel installation.

The CFMO has also implemented vermicomposting facilities that turn tree leaves into organic matter for campus biodiversity. This complements the maintenance of green parks throughout campus and the installation of carpark trellises, which provide shade and are made from repurposed tree residuals.

Despite these efforts, Delocado states that educational aspects must also be highlighted as structures alone are not enough to promote ecological conversion.

For instance, initiatives like pollinator pockets—which are wildflower patches and grasses that promote pollination and improve the health of the larger campus ecosystem—are paired with signages explaining the pollination mechanism and the species involved.

Reconciling with nature

As part of their multi-sectoral sustainability efforts, the AIS has recently worked with the Council of Organizations of the Ateneo – Manila, the Ateneo Environmental Science Society, the Ateneo Biological Organization, and the Sanggunian to start the Green Nudges Project.

Delocado envisions that these initiatives could shape the community’s environmental consciousness, making its members acutely aware of the ecology integral to the Loyola Heights campus.

Despite these endeavors, recent developments, like the North Carpark renovation that has led to uprooting of trees, have sparked debates on balancing development with sustainability.

Delocado acknowledges this complexity, noting that sustainability efforts must navigate competing community interests. “That’s what we feel is an often understated aspect of sustainability discussions—that we are looking at one reality but we are seeing it differently,” he pointed out.

To foster more open discourse, the AIS encourages the community to participate in public consultations on the University’s action plans on sustainability, climate, and biodiversity to share their insights before the finalization of these documents.

Anticipating drastic changes across the global climate, future campus projects revolve around an urban ecology that has been cultivated over the last seven decades.

As the climate crisis continues to shape urban spaces, Ateneo is challenged to balance development with environmental stewardship. The ongoing dialogue within this living laboratory is reflected in the ecological impact of campus development projects—an issue closely watched by the Ateneo community.