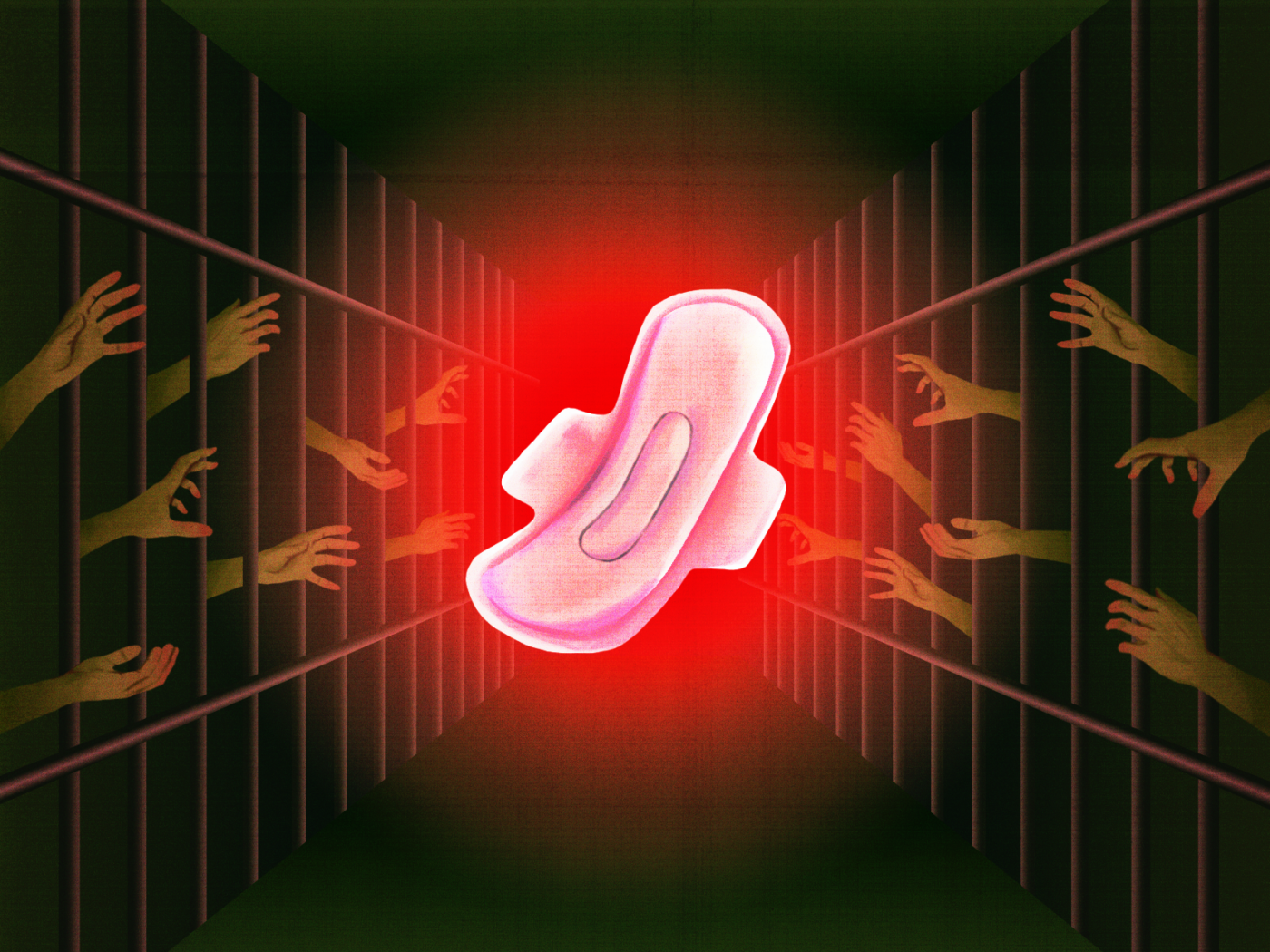

Women Deprived of Liberty navigate the complexities of managing their menstrual health behind bars, highlighting pressing needs for dignity, support, and improved care.

TO MENSTRUATE is a dignified human experience. As women require different needs with their periods, having access to essential sanitary facilities, services, and resources becomes essential for them to manage their menstrual health confidently and without shame.

For Women Deprived of Liberty (WDL), menstruation is both a neglected and inevitable struggle. The compounded realities of womanhood and incarceration often complicate access to such necessities, denying them the dignity to manage a natural bodily function.

A flux of dignity

In the Female Dormitory of the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) Marikina City Jail, the WDLs have settled into their daily routines: morning visits, mid-afternoon lunches, and daily bathroom cleanings. Even in the mundane, life inside a correctional facility presents a unique set of challenges for menstruating WDLs.

Soppia, a detainee, recalls getting her period at age 11. Lacking prior knowledge, her school and community became her foundations in navigating her menstruation. Looking back, she humorously recalled how adamant they were about obeying cultural myths. “Sa unang regla, ilalagay daw sa mukha [at] ‘wag daw maliligo sa ulan. (During your first menstruation, you must apply the menstrual discharge on your face, and one should not bathe in the rain),” she recounted.

However, since being injected with birth control, Soppia had irregular menstruation—a common yet stigmatized gynecological issue in the Philippines, bringing added health risks and social shame.

Carmelita, another detainee in the same facility, shares a similar experience with the stigma surrounding menstruation in her younger years. Shaped by cultural beliefs and family perspectives, she notes how she grew up viewing irregular menstruation negatively, particularly due to its link with fertility concerns.

This stigma does not just affect perceptions—it also influences the treatment women receive within the facility. For instance, Carmelita shares the frustration of needing more sanitary napkins for her month-long period, a plea that was met with skepticism and disbelief from other inmates, as understanding and empathy for WDLs’ menstrual challenges remain rare.

Soppia and Carmelita’s struggles reflect a larger issue that affects women globally. When women’s needs go unmet, barriers to menstrual dignity increase—raising critical questions about whether correctional facilities truly address gender-specific care.

Gendered pains

JO2 Beverly Gaong, RN, a uniformed nurse in the female dormitory, elaborated on the systems that BJMP has imposed for these circumstances. Each week, hygiene kits are distributed to the female inmates. These usually include essentials such as toothbrushes, toilet paper, at least three sanitary napkins, towels, cotton buds, and soap.

The dormitory also provides a restricted quantity of “Those Days” sanitary napkins, known for causing minimal allergic reactions. WDLs are permitted to receive additional supplies from visitors, who can come up to six times a week, and extras may be provided upon request.

Moreover, medical care in the facility is generally accessible, with regular medical missions from private organizations and local government units providing OB-GYN consultations and cervical screenings three to four times a year.

However, despite the best efforts of the medical staff and specialized nurses, health conditions in the dormitory are heavily impacted by extreme overcrowding. Nurse Gaong reports that there is a congestion rate of 582%, with 254 inmates housed in a space designed for only 28 people. This overcrowding explains the increased stress levels among inmates and the limited distribution of sanitary napkins to prevent hoarding.

Furthermore, financial provisions for the BJMP are dependent on government allocations and income generated from livelihood programs, which can be used to purchase extra sanitary napkins.

Despite the many constraints, inmates like Soppia and Carmelita remain hopeful for greater access to sanitary products and more frequent OB-GYN consultations within the facility. For now, they have expressed adequacy in the respect they receive as menstruating WDLs.

The life we bleed

While the menstrual dignity of Soppia and Carmelita remains intact inside the BJMP Marikina City Female Dormitory, WDLs in other holding facilities within the Metro may not have the same fate. Reports show that access to sanitary napkins in other sites are monopolized by co-ops and restrictive jail regulations. These narratives strive to bring attention to those beyond their bars, highlighting the need for gender-sensitive policies in public correctional facilities.

The spectrum of WDLs’ lived experiences reveals one truth: menstrual dignity demands more than a one-size-fits-all response. More than mere statistics, their humanity and womanhood are recognized by the affirmation that the right to health is universal, undiminished of taboo or stigma.

“Sana po mapagbigyan din na makapagpacheck up sa OB-GYN lalo na sa mga irregular, kailangan din po kasi maasikaso kasi di po magawa habang nasa loob (Hopefully we can also be given a chance to have check-ups with the OB-GYN, especially for those with irregular periods, [sic] since we cannot do so in the facility),” Carmelita expresses.

Undeniably, life does not cease behind bars. As long as gender-specific care remains inaccessible to all, WDLs will continue to bleed their ironclad truths—an essential right that ought to be available to all, especially for those who lack the freedom to secure it for themselves.