More than a referendum on the Marcoses and the Aquinos with the 1986 Snap Elections, the EDSA Revolution in 1986 displayed the “People Power” as it became a force to restore civil liberties to a torn society that spent nearly two decades without them.

Since then, annual commemorations of EDSA I have often been done as a celebration of Philippine democracy itself, and efforts to restrict or undermine memories of the watershed period can feel like attacks on the democracy institutions strived for nearly four decades ago.

In recent years, EDSA has remained a hotspot for active political assemblies following the “spirit” of the first People Power with at least two mass events remembered as 2001’s EDSA II and III. With no “EDSA IV” in sight just yet, the continuation of pro-democracy protests has gained a separate yet derivative character of activism.

The memories of EDSA I as a movement of the united Filipino masses blur as time progresses—ever-susceptible to downplays and reductions in its role of restoring democracy to the country, alongside other regional efforts. As such, the fight for freedom against political injustice continues today as a derivative of the “People Power” of 1986.

With a growing generation of Filipinos born after EDSA I, a question arises: what does it truly mean to keep the “spirit” of EDSA alive?

Since EDSA I, Filipinos have continued to bring the fight for their causes to the streets, noticeably seen in the Pink Movement in 2022 to the recent Iglesia ni Cristo (INC) Peace Rally last January. However, succeeding mass movements within the country have seemingly failed to reach the political and social impact of EDSA I.

A key factor underlying the inability to recreate another influential mass movement is the lack of intersectoral cooperation toward the initial goals the “People Power” exercise sought to restore—the re-establishment of constitutional power back to its citizens. The recent INC rally, for instance, mobilized thousands but it was seen as insular, failing to extend its reach beyond its religious community.

With growing political polarization, deterrence to organize toward a common goal becomes no surprise. The essence of the Pink Movement was to tap into compassion and understanding as a means to unite voters on opposing sides. However, the results of the elections proved that ideological gaps run deep. Many Filipinos are not only politically divided, but they are also unwilling to engage with opposing perspectives.

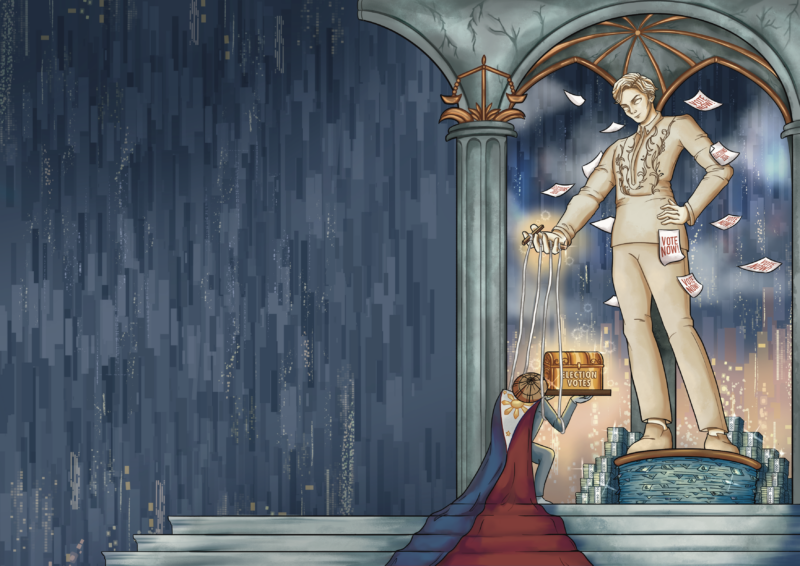

Although the current Marcos administration has “acknowledged” the essence of EDSA I, they have made subtle yet calculated efforts to chip away at its history. For one, the recently implemented MATATAG curriculum changed Diktadurang Marcos to Diktadura in textbooks, omitting his name from this label. Outside of the classroom, the administration’s efforts further manifested as they demoted the EDSA Revolution to a working holiday.

Needless to say, when the nuances and ambiguities that sustained the dictatorship and led to the EDSA People Power Revolution are erased, the desire to recognize and protect what EDSA I fought for also fades away.

But the challenge is not merely about remembering history—it is also about unlearning complacency. Resilience is usually used to praise Filipinos for how we bounce back from adversity, but this can also be weaponized to justify inaction. This level of pagtitiis can be dangerous, as we are prone to simply accept whatever is thrown at us without question.

Our tendency to form strong opinions works to our detriment, too. Once we make up our minds—like when we pick sides in today’s polarizing political rivalries—we are often prone to confirmation bias. Moreover, we tend to turn a blind eye to ideas that are against what we think, hindering us from truly acting. These values directly connect to Filipino patience as well; it takes a lot for Filipinos to say that enough is enough. After all, it took us 20 years for EDSA I to happen. When people are conditioned to endure rather than resist, the space for meaningful change narrows. Democracy is not lost in a single moment of corrupt governance; it erodes gradually when citizens no longer demand better.

Without a strong sense of undivided nationalism—certainly not as strong as in 1986—one of the only concrete ways to instill positive change nowadays is not just to vote for the right people, but also to understand why we vote for them. Politics can be a difficult topic to discuss, but engaging with it beyond the colors and complacency is imperative to shaping a more transformative and proactive voting population.

Perhaps another EDSA People Power Revolution will never happen. We tried to do it again—twice—but these iterations failed to truly live up to the original’s name, and the many other Filipino movements inspired by it never had the same kind of impact either.

Going into EDSA I’s 39th anniversary, we always say to never forget, but we must do more than just remember history. Instead, we must remember the essence of “People Power”—of banding together and collectively retaliating against injustice through peaceful means. At the end of the day, achieving genuine change necessitates Filipinos’ unity rooted in our shared struggles, not from being divided by political differences.