AS THE highly crucial 2025 Midterm Election nears, the real problems of the Filipino people remain drowned out as another set of egotistical campaigns is put forth. Politicians scramble to take control of popular opinion through showbiz-esque glamour in the face of economic hardships and political strife.

Although the official campaign period does not begin until February 11, candidates have already taken to billboards, posters, and mainstream media to present themselves to the public. Some candidates have even ramped up their presence through such platforms before the formal filing of their certificate of candidacies.

While there has been a constant call for an end to traditional politicking and its entrenched mechanisms, candidates from prominent political dynasties or dubious backgrounds continue to top the pre-election polls, seemingly conditioning Filipinos for their inevitable win.

With this trend, discussions pertaining to the elections continue to include the idea of imposing additional qualification requirements to assess the fitness and competence of political aspirants. However, any hopes for change in a deeply flawed system—which has long enabled unchecked political power and fostered corruption—greatly entails the participation of the people.

Deeply populist

Throughout Philippine history, candidates have found various ways to strike a connection with their voters. One of the most popular campaign tropes is the practice of populist politics, where the political aspirant paints themself as “one of the masses,” or not one of the elite.

This concept was already evident when the revolutionaries of the Katipunan rallied the Filipino people towards the struggle for independence. Despite being organized and led by ilustrado elites, the movement was still considered as “masa” or one by the masses due to the former’s promotion of the absolute idea of kalayaan (freedom).

When the Philippines gained independence and established its own national government, this trend remained and became a mainstay in Philippine politics. One of the earliest political figures to successfully embody this trend was Ramon Magsaysay, who was dubbed as “The People’s President” for being a man of the people up until his tragic death.

However, this tactic gradually evolved into a political machinery to gain leverage over the people. The late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr., a populist known for his “from zero to hero” narrative in his campaign propaganda, sold the concept of a new society that is free from starvation, hardship, and terror. When the Marcos family became the “elite,” Corazon Aquino’s campaign emerged as the face of the populist movement.

In the decades that followed, this same power trope reappeared in different campaigns across various rivalries, such as Joseph Estrada’s “Erap para sa mga mahirap” (Erap for the poor) and Rodrigo Duterte’s anti-establishment campaign cemented by the slogan “Change is coming.”

Today, this trend of populism has taken on a different form: personality politics. To gain relevance, candidates make their names synonymous with buzzword-filled promises— packaging these efforts in catchy jingles, publicity stunts, and propaganda that align with the voters’ interests.

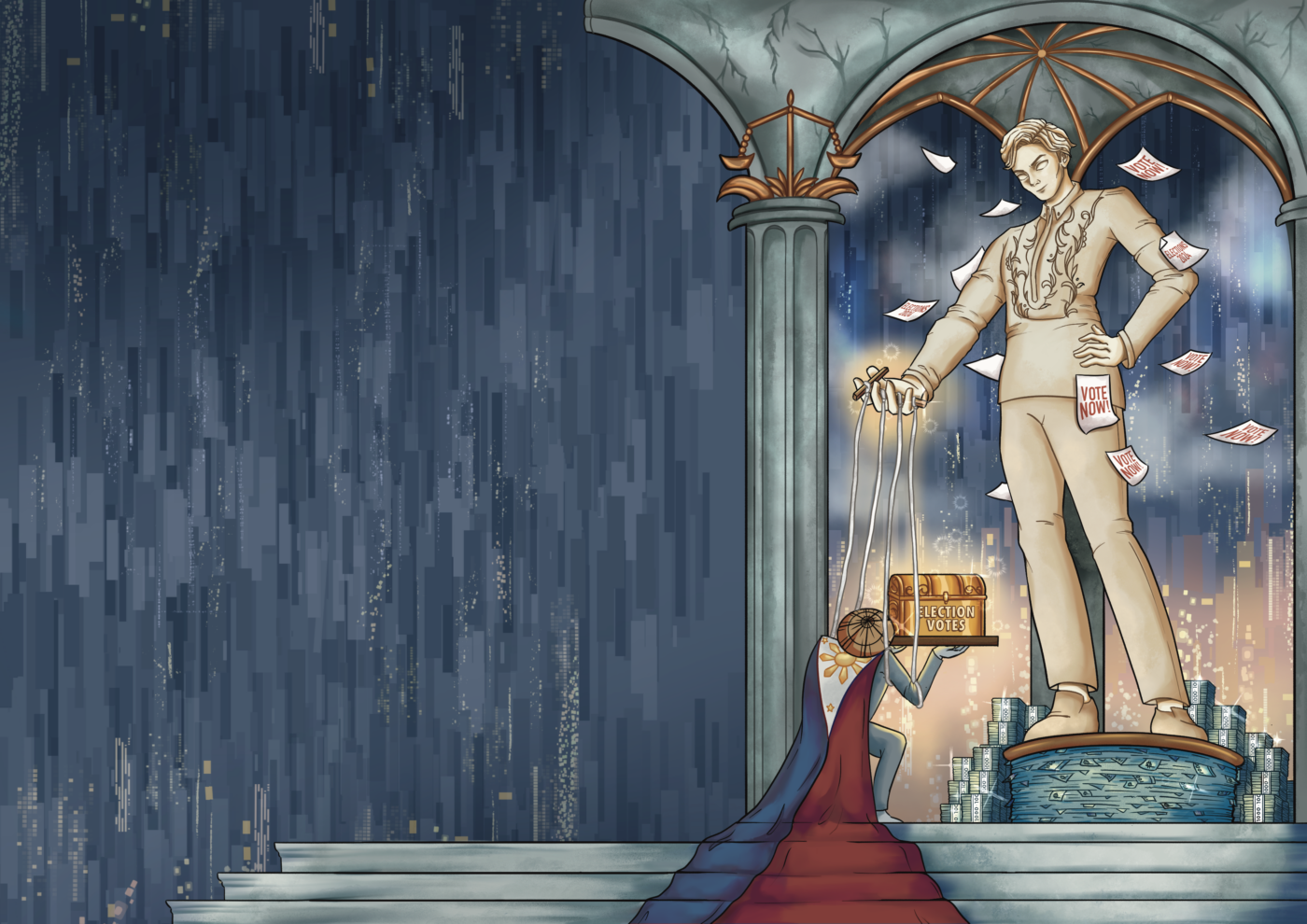

An auctioneer’s democracy

The evolution of populism over time has unfortunately skewed people’s perception of what politics is and how elections should be won. Now, the masses tend to prefer voting for someone they already know and are familiar with, especially those who grace their television screens daily.

In next year’s elections, the ballot will bear a plethora of prominent personalities from various affiliations, may it be entertainers, social media influencers, or even journalists. Worse, some even face charges or are currently in detainment, such as Apollo Quiboloy.

Needless to say, taking control of public opinion and awareness is central to an election victory. This dynamic unfortunately incentivizes established names in popular culture to run for public office.

Moreover, members of known political families heavily bank on their last name’s reputations, with almost, if not everyone even inheriting their family’s campaign machinery. Despite their privileged high-class backgrounds, they pitch themselves as candidates of the people by taking advantage of their financial resources to launch publicity campaigns.

Where propaganda does not work, brute force is employed. Philippine elections have always been regarded to be one of the dirtiest in the world. In fact, according to the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines and election watchdog Kontra Daya, the recent 2022 national elections were “not free, honest, or fair by international standards.”

Because of this reality, the democratic process of elections is seemingly won by the highest bidder; whoever has the deepest pockets gets the most votes. This system is just profoundly ironic as it ultimately favors the most “masa” candidate, especially when the means taken to achieve this image goes against everything that is masa.

Undoubtedly, this current trend which favors showmanship and popularity over genuine platforms erodes the validity of democracy. If this self-serving practice of politicians is left unchecked, the country’s democracy risks devolving into a shadow monarchy ruled by the opportunistic elite who masquerade as candidates “for and with the common Filipino.”

While it is no easy task for Filipinos to go against their penchant for populist personalities—as seen in recent results—power still ultimately lies in their numbers. As such, the challenge remains on whether or not they choose to act or let themselves remain in stagnation, complicit in this national farce.

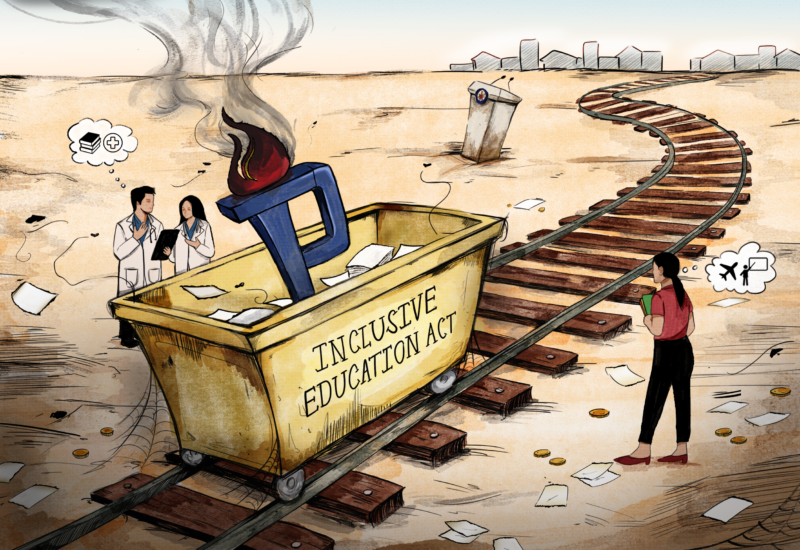

Voting forward

The urgency of a clean, fair, and voter-centric election continually needs to be emphasized now more than ever. In challenging the norm and addressing this cycle directly from the roots themselves, the Filipino people must also assess candidates’ backgrounds better, ensuring that the public good is truly their priority.

More importantly, there must be a call for stricter nuisance candidate classifications. Conditions must already include those who contribute no meaningful platforms but mere entertainment and noise to the electoral process and public service at large. Individuals with prior convictions related to betraying the public trust must be barred from office, even those pardoned by the president.

The Commission on Elections must consider a more rigorous vetting process, assuring that all who make it to the ballot are capable of fulfilling their duties once elected.

Ultimately, the burden to run platform-based campaigns should fall on the shoulders of those seeking a seat in government. As we urge these power-seeking candidates to heed the call, the 68.6-million Filipino voters must stay vigilant against false narratives and flash campaigns because in the end, they deserve to be truly represented by competent candidates who have legitimate and grounded platforms.

The true power of democracy lies in a system where voters are genuinely empowered. Thus, it is time to move beyond the theatrics and restore the integrity of the electoral process.