CONCERNS OF commercialization—generally defined as the process of introducing a product into the market for financial gain—have recently surfaced on various higher education institutions (HEIs) in the country.

Since last year, the University of the Philippines’ Philippine Collegian has released several articles about the DiliMall, a privately managed three-storey shopping center that threatens the displacement of previous stall owners due to its high rental rates. In a recent editorial, the publication pointed out the threat posed by the “unrestrained continuation of commercialization” to the principles of community participation.

Within the Ateneo, faculty and student leaders are noticing this trend and calling for a critical assessment of the possible manifestations of commercialization within the campus.

On the horizon

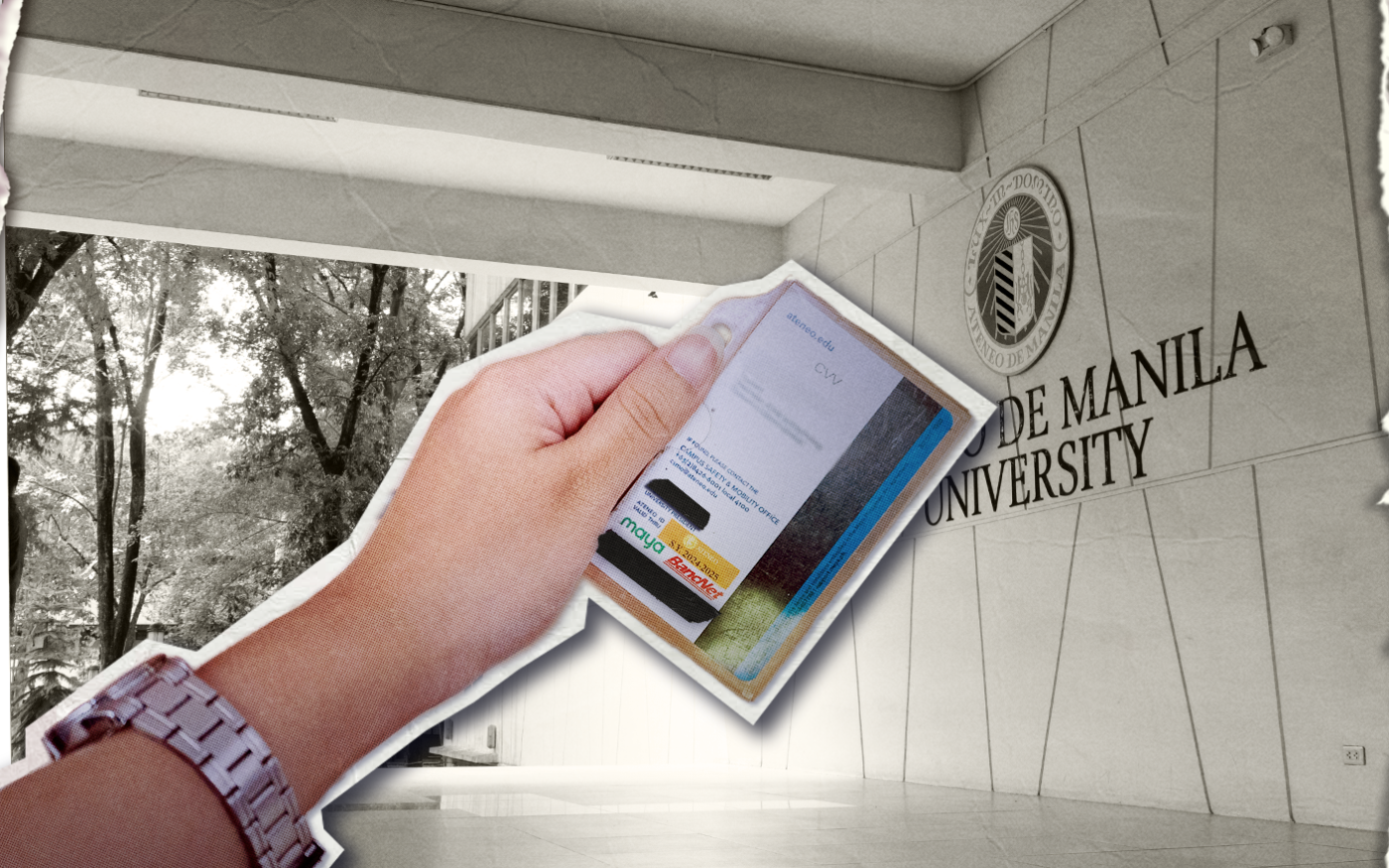

Last September 9, Political Science Department Chair Carmel Abao, PhD voiced her concerns in a Facebook post regarding the new University ID, which also functions as a Maya Bank card. She asserted that the feature ties the card to consumerism and undermines its primary purpose for security and legitimacy.

While Development Studies Instructor Erron Medina acknowledges the convenience of the Maya-powered card, he echoes Abao’s sentiments on how the initiative could compromise the main purpose of IDs and align more closely with commercial interests.

Meanwhile, for 4 AB Economics Representative Eduardo Pitero III, commercialization happens when markets of external providers enter campus spaces with profit in mind. He mentions the potential entry of a private concessionaire replacing the Ateneo Multi-Purpose Cooperative (AMPC) in the Gonzaga cafeteria as a possible example of such a phenomenon.

Pitero explains that while AMPC is also for-profit, a cooperative’s purpose is more “democratic” than a private business, as benefits of the former go to its members, while the latter’s proceed to those with capital.

Beyond visible spaces like cafeterias, Medina underscores that the subtle integration of commercialization also appears in student initiatives, such as those involving markets and priced tickets.

He expounds that while these student projects with business activities are not inherently negative, they reflect a commercial impulse that encourages market-oriented behaviors and increases commercialization.

According to him, commercialization is also commonly seen in other HEIs through the rental of university facilities, as they seek out profit by leasing their venues. He adds that “lesser known” institutions would try to generate revenue by pricing student activities, such as field trips and sports events.

Purpose and revenues

While acknowledging the presence of commercialization aspects in some of the day-to-day activities on campus, Ateneo Center for Economic Research and Development Director Ser Percival Peña-Reyes, PhD mentions that these commercialization efforts are driven by the need to generate revenue and sustain operations.

Peña-Reyes explains that several campus establishments like cafeterias have to be profitable to sustain themselves, while ensuring affordability for its student market. He notes that healthy competition can be observed among food stalls in the Ateneo, which prevents any overpricing tendencies. He also points out that the Ateneo is a non-profit institution despite being a private university, thus requiring it to seek donations and additional sources of funding.

With this, Peña-Reyes emphasizes that aside from those establishments that reasonably need to have profits for survival, he sees no other “bothering” forms of campus commercialization. According to him, there is nothing concerning with focusing on efficiency, wherein better services can be reaped at a lower cost.

In some of these cases, Medina recognizes the role of commercialization in easing an institution’s processes and transactions. Amid these instances, Pitero acknowledges the reality that many Ateneans fail to miss the effects of commercialization, especially in an academic setting, as these happen very slowly and only in increments.

“With a lot of things going on, like we have to attend classes, we have our own orgs, we have our own family life, it’s easy to just overlook [the impacts of commercialization] and not think about it. [As such,] our level of awareness could have some improvement,” Pitero explains.

Similarly, Samahan ng Progresibong Kabataan (SPARK) – Katipunan Spokesperson Miguel Angelo Basuel has noticed a limited awareness of commercialization among Ateneans, resulting in the normalization of profit-seeking behavior as an “everyday occurrence” on campus.

He adds that most students may not recognize its impacts until they become pronounced, highlighting how changes on campus may not be a conscious choice by the University community.

Following this, Medina expressed his concerns on the possible impacts of commercialized activities and practices in the way learning is facilitated in academic institutions.

“Mahirap magkaroon ng critical examination of market effects if you are within an environment that is dominated by market principles and practices. Lumiliit kasi ‘yung espasyo for intellectual exploration kung ‘yung mga spaces sa loob ng university ay commercialized,” Medina expounds.

(It’s difficult to have a critical examination of market effects if you are within an environment that is dominated by market principles and practices. It’s because spaces for intellectual exploration become limited if there are university spaces that are commercialized.)

While Medina does not think the Ateneo is heavily influenced by such market principles at present, he hopes for a future where classrooms remain safe spaces for students and professors to academically discuss and critically examine economic realities.

Transparency and responsibility

Amid the seemingly growing commercialization efforts in the country, Medina urges students to pay attention to its growing presence and long-term impacts. “The task is to always monitor and carefully watch these moments and tendencies to prevent them from really gaining too much ground doon sa loob ng University, kasi ang gusto natin mangyari ay ‘yung University manatiling isang independent space,” Medina emphasized.

(The task is to always monitor and carefully watch these moments and tendencies to prevent them from really gaining too much ground inside University because we want the University to remain as an independent space.)

Subsequently, Pitero highlights the need to reassess the ultimate goal of improvement efforts within the University. To do this, he underscores the significance of transparency as it enables meaningful dialogue between the administration and the University’s stakeholders.

Sharing the same sentiments, Basuel reiterates the student body’s longstanding call for an institutionalized platform for hearing community concerns. He states that the inadequate awareness of commercialization is a “symptom” of the lack of transparency and meaningful dialogue.

Furthermore, Medina asserts that students must also acknowledge how their privileges weigh in commercial behavior within the University spaces. He explains that these businesses will not receive traction if they do not expect any returns from the population.

Thus, as discussions on commercialization in HEIs continue, the awareness of the Ateneans on commercialization plays an integral role in ensuring that the University spaces remain as genuine and unrestricted places for learning.

Editor’s Note: The article was updated to clarify the difference between a cooperative and a private business.