THE PHILIPPINES has not had a true strongman as its head of state for nearly two years. Compared to his predecessor, President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. has employed a drastically different rhetorical style. While the previous president was defined by his reckless rhetoric, Marcos Jr. has taken a more diplomatic approach, especially toward foreign leaders for whom former president Rodrigo Duterte showed little regard.

For some, this shift in presidential behavior may arguably signify that the Philippines is moving past the excessive populism that brewed brutal campaigns such as the war on drugs. However, the effects of populist politics found their roots long before Duterte’s administration and continued well after it.

Deeply-rooted disaster

The implementation of Project Double Barrel during the beginning of Duterte’s administration has commonly been marked as the beginning of the Philippine war on drugs. However, this action did not happen in isolation, as byproducts of populism from prior administrations helped set Duterte’s anti-drug campaign in motion.

University of the Philippines Diliman Anthropology Department Senior Lecturer Dr. Gideon Lasco pointed out how the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act, signed into law by then-president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo in 2002, was used as a precedent for actions such as Duterte’s drug war. The Human Security Act of 2007, which was heavily criticized during its passage, also served as the basis for Duterte’s Anti-Terror Law.

“We cannot [think of these drug policies in] a vacuum. Otherwise, these strict policies will keep recurring and [be] subject to abuse,” Lasco emphasized.

Duterte capitalized on pre-existing stigma surrounding drugs and communism, earning him the highest approval ratings of any modern Philippine president. Among the reasons why he was popular in surveys was a “perceived decisiveness and diligence,” which came from taking such hard stances on hot-button issues.

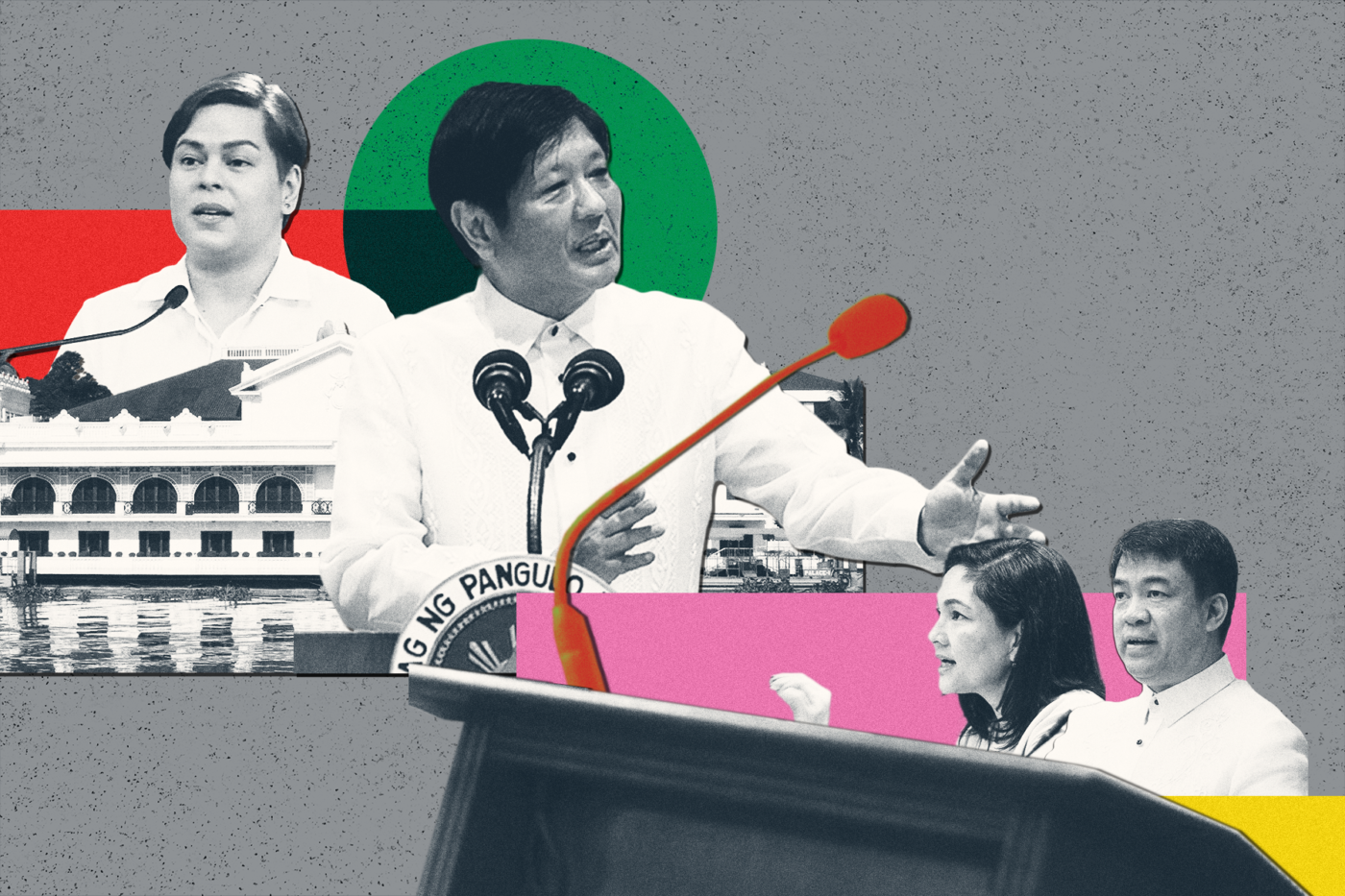

Even after Duterte left office, the large following he amassed through his strong-arm populist rhetoric led to the political success of people that heavily marketed themselves as supporters of his cause, such as his family, close associates, and running mates. Marcos Jr. enjoyed not only the rehabilitated popularity of his late dictator father but also the benefits of having a Duterte in his coalition—which was crucial to his victory in the 2022 national elections.

Other Duterte-allied politicians also use the former president’s large following to push populist causes. For instance, Senators Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa and Christopher “Bong” Go continued fighting against the ICC’s probe into Duterte’s drug war. They also defended the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict against charges of red-tagging and other grievous abuses of power.

Exploitation epidemic

Oftentimes, populism is the result of institutional failure rather than the cause of such. In the Philippines, populist rhetoric gained its foothold through the public’s frustration with the political elite, which festered in post-EDSA administrations.

During this period, the country experienced a general trend of upward economic growth. However, this growth excluded the majority of the population, largely benefitting foreign investors and big businesses. Instead of redistributing agricultural land to the nation’s poorest, land reform programs divided these properties toward commercial use, further miring farmers in landlessness and generational poverty.

Although Duterte and Marcos are sons of elite political dynasties, they often position themselves as outsiders to such corrupt institutions, disguising themselves as opponents of the elitist regime.

Such political families, in fact, campaign through short-term “silver bullet” promises such as massive anti-corruption reform, complete illegal drug elimination, and extreme price deflation. These promises appeal to people who have long struggled to put food on the table, presenting them with hopes of a country free from drug-related crimes or a return to an economy of Php 20 per kilo of rice.

Consequently, these beliefs pave the way for citizens’ tolerance of even the most radical policies. “Our fundamental problem, as far as drugs are concerned, is that people believe that drugs are evil, and this is holding back any chance of progress, because if you believe that people who do drugs are evil, you support harsh punishments,” Lasco stated.

Contrary to the reforms populist politicians supposedly intend to bring, legislation has been slow to address the fundamental problems that plague the nation, instead further entrenching the elite within the nation’s structures. The two presidencies have been marked by supermajorities that bulldoze policies through the other branches of government with little to no opposition. With the mandates of an overwhelmingly approving electorate in hand, blatant political maneuvering has only been met with even more staunch support, further emboldening politicians.

Seeking solutions

As populism is deeply integrated within the country’s fundamental systems, it can be difficult to pinpoint exact measures with which to combat it. Some scholars have noted that the Philippine political process itself is flawed, as the country’s law consecrates a state of “hyper-presidentialism,” wherein the majority of political will is concentrated on an individual head of state.

In an attempt to provide solutions, some political organizations recommend the revitalization of a strong party system with clear ideological differences and hard political biases. These parties prevent power from being concentrated into any individual by institutionalizing internal vetting processes and organizing legislative initiatives for its fielded candidates and marketed platforms.With how deeply rooted populism is in the Philippine context, it must be countered on numerous sides—in the creation of ideologically-based coalitions and through the undoing of the country’s socioeconomic hardships. As long as the country’s public officials enjoy the electorate’s unconditional support, they will only wield it in their self-interest.