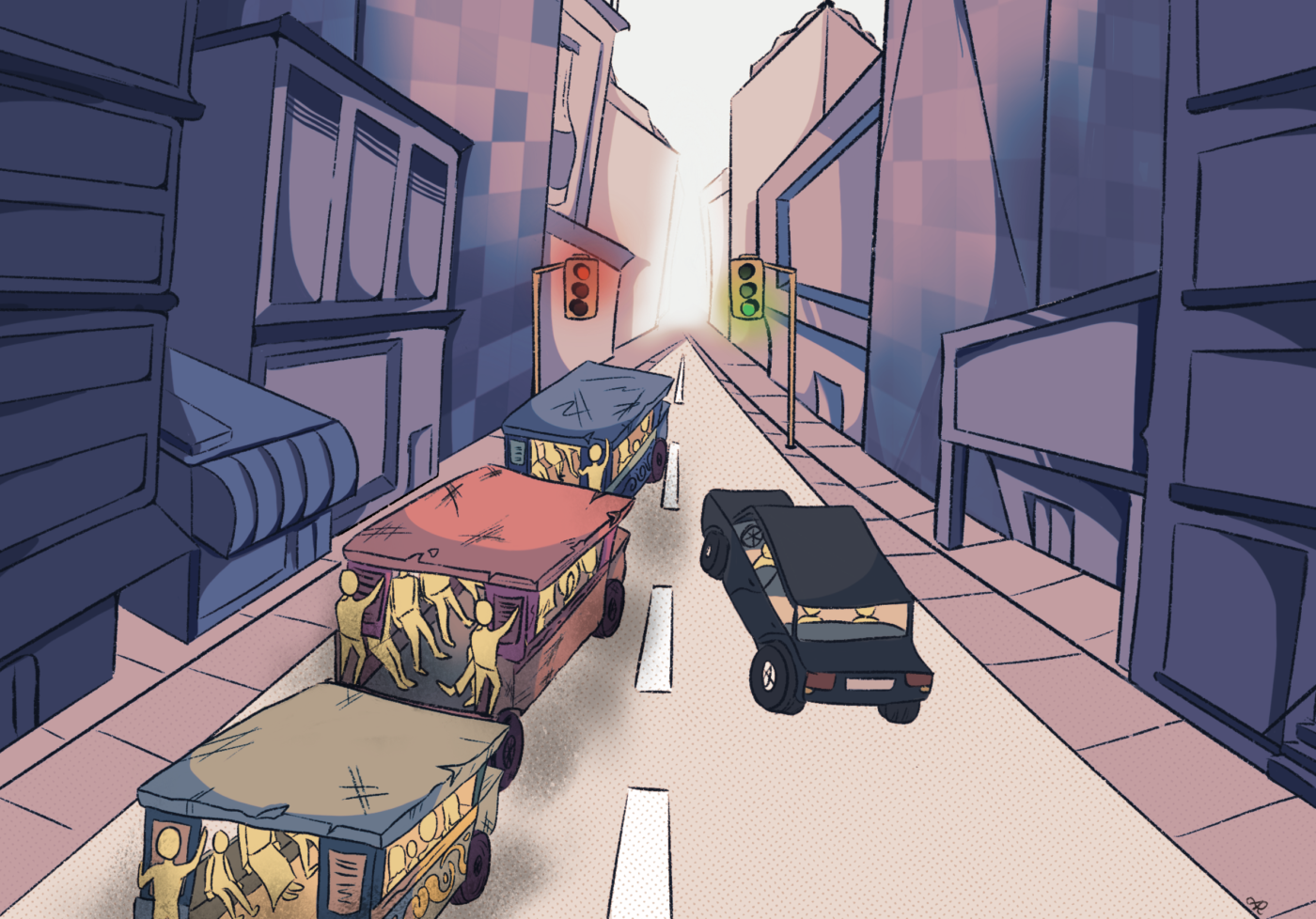

THE TRANSPORT system in the Philippines paints an upsetting picture: roads cramped with traffic, sidewalks packed with people waiting for jeeps and buses, trains crowded with commuters, and paths virtually unusable for pedestrians and bikers.

In 2022, Manila ranked fifth worst among the world’s public transit systems. Commuters face a 71% increase in travel time during their daily transit as compared to their supposed duration during free-flow traffic. The congestion is further coupled with poor quality and connectivity to other regions in the country.

As the country’s transport system seeks evolutions, legal frameworks continue to solely service the private transport sector, further dragging down their public counterparts.

Two-way street

Divisions between the use of public and private transport sectors are marked primarily by an economic split. Although public transportation is meant to cater to the general public, inefficient facilities and overcongestion deter many from regularly using them, especially by those who can afford private vehicles.

Despite the majority relying on public transportation, government agencies exert more efforts into improving infrastructure for private vehicles through road expansions and parking construction. To illustrate, only 22% of space is allotted for public transport, with the rest used for roads.

As such, many commuters have expressed that little attention is given to sustainable transport options like walking and biking as well, with dangerous lanes and crosswalks all around. In a 2020 survey by the Social Weather Stations (SWS), 87% of Filipinos stated that they believe the government should exert more effort into public transportation over private.

Likewise, transport advocacy network The Passenger Forum’s 2022 survey indicated that 96% of its respondents find the supply of Public Utility Vehicles lacking. Moreover, 97% of the respondents express their hopes for more trains and train lines.

Shared-Use Mobility Center Chief Executive Officer Benjamin de la Peña echoed this sentiment, stating that expanded transportation options should be given more attention in policy-making. “A good metropolitan area would give you better options than driving a car. Public transportation should be faster, [and] walking should be safer,” he explained.

With mobility improvements in Metro Manila focused on enhancing the experience of car users, commuters have long stressed the need for the government to prioritize public transport.

Family favorite

The heavy amount of investments that the country has made in developing roads over public transportation has reflected a car-centric mindset. Examining how the government spent its road program budget from 2010 to 2021, the Move As One Coalition saw that only 1% of the funds went into road-based public transportation, with the lion’s share going into road expansion and widening.

This heavy emphasis on road expansion leads to induced demand, as adding more spaces for vehicles only encourages citizens to use up the additional road. As such, continuous road expansion not only fails to solve the problem of congestion but also pushes private vehicles as the primary mode of mobility above all other options.

Development Studies professor Segundo Joaquin Romero Jr., PhD further stated that while currently being improved, the Metro Rail Transit and Light Rail Transit “have yet to ease congestion.” “The BRT mode has the best potential for alleviating traffic congestion, but the [EDSA] Bus Carousel remains a poor interpretation of what has been a powerful and transformative transportation mode in other countries,” he added.

A similarly car-centric approach manifests in policies that aim to ease traffic congestion. Currently, laws regarding traffic regulation have only prompted the purchase of more cars, such as the Unified Vehicular Volume Reduction Program, otherwise known as the number coding scheme. As de la Peña pointed out, number coding only targets people who can already afford a car, so restricting when they can use their vehicle would only incentivize them to purchase a second one.

These concerns have also manifested in Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA) Regulation No. 24-022 series of 2024, which prohibits e-bicycles, e-tricycles, tricycles, pedicabs, and pushcarts from traversing national, circumferential, and radial roads.

According to the MMDA, this directive aims to decrease the occurrences of vehicular accidents. However, Move as One Coalition co-convener Roberto Siy Jr. asserted that this ban would only exacerbate traffic congestion as it further promotes car use.

Nurturing neglect

The government’s car-centric approach evidently runs counter to the needs of the predominantly commuting urban masses, leading to dissatisfaction with the current state of public transportation.

To combat the dominance of car-centric policies, de la Peña suggested a number of ways in which the country can put public transportation development firmly on the driver’s seat.

First, by implementing congestion pricing, which de la Peña described as “the only proven model to reduce traffic congestion,” and adding hefty certificate of ownership fees, car usage would not only be disincentivized, but would also help fund public transportation programs.

de la Peña added that public-private partnerships could explore the prospect of value capture mechanisms involving utilizing train stations as centers of development. Moreover, he emphasized the need to invest in pedestrian sidewalks rather than parking incentives that would easily succumb to induced demand.

Romero also emphasized the need for a paradigm shift through policy. He stated that incentives should be given to carpooling, while parking in public spaces should be paid.

Furthermore, he cited the importance of transformative approaches to promoting inclusive mobility, such as expanding lanes for bicycles and public transportation, while reducing road space for cars.

“Innovative solutions, such as off-site public parking that is connected by buses, monorails, and e-buses to common destinations such as Ateneo should be generated to de-clog main arteries such as Katipunan Avenue,” he added.

As such, the push for sustainable and inclusive mobility has been gradually building up its groundswell not just from the academe, but also from the grassroots. With the harsh commuter experience growing increasingly dire, the government’s mobility-related policies will primarily dictate whether the movement toward quality public transportation will get further derailed or be put back on track.