THE PROXIMITY of Manila Bay to the Philippine urban capital has subjected it to decades of land reclamation—the process of creating new land from bodies of water. Having grown into a popular site for urban development, the bay has become the topic of discussion among lawmakers and environmentalists who question the legitimacy and necessity of reclamation in the area.

Under Proclamation No. 2146, major reclamation is defined as an environmentally critical project. This means that the chosen reclamation areas must undergo an environmental impact assessment (EIA) prior to the issuance of an environmental compliance certificate (ECC). Primarily, the EIA serves to evaluate and predict the likely impacts of a project for the purpose of putting prevention and mitigation measures into place, or if necessary, for the local government unit to reject the project.

However, Environmental Science Professor Dawn Satumbaga, MSc observed that in the EIA, “There are no specific thresholds to determine when a project should be rejected [and] what is considered [as a project having] ‘significant impact.’” Further, Satumbaga noted that the current EIA system evaluates projects individually as opposed to cumulatively, thus creating gaps in the total impact assessment of reclamation projects.

Members of scientific, environmental, and fisherfolk groups also maintain that dialogues must not be limited to government agencies and proponents. They suggest that dialogues must involve civil society, experts in environmental and social governance, and most importantly, communities affected by proposed reclamation projects.

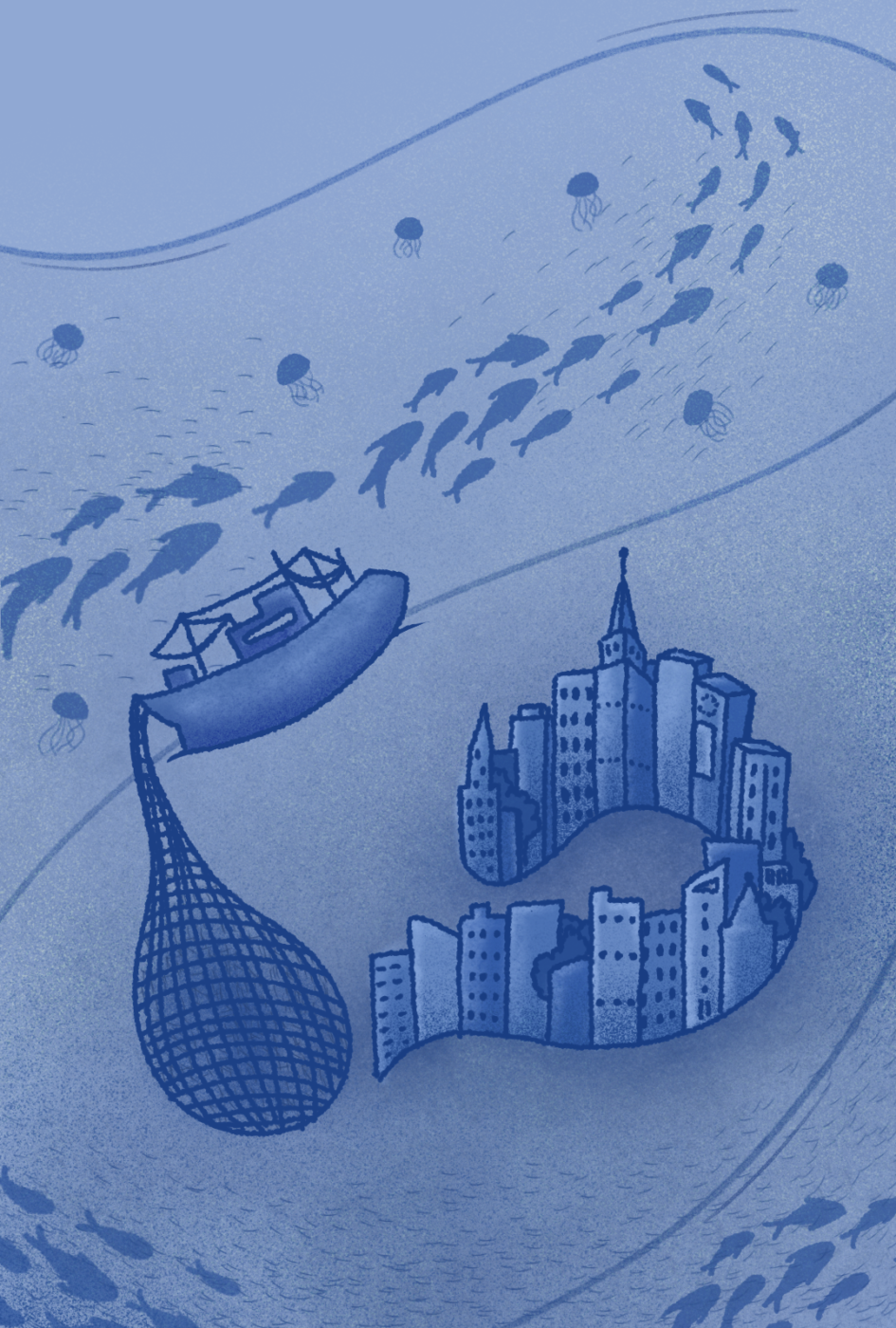

For instance, communities that reside near Manila Bay are reliant on its supply of sardines, mackerel, and other fish species for food and livelihood. Consequently, environmentalists purport that the compromise of aquatic life there would in turn affect livelihood should reclamation push through.

Elsewhere in the country, reclamation projects are likewise perceived as threats to nature and biodiversity. One such project is the Bulacan Aerotropolis, a 2,500-hectare reclamation project that aims to aid Manila’s flight congestion problem. Given the possible consequences not just to the environment but also to livelihoods, the project faced strong opposition from fishing communities and environmental groups who claimed that they had been denied access to the supposedly public EIA of the project. However, the project was granted an ECC in 2019 and has since been the suspected cause of mangrove tree disappearances in the Bulacan province.

Such reclamations extend beyond Luzon to Central Visayas, where up to 3,000 hectares of land and water have been affected in Cebu and nearby areas, leading to losses in marine life, fisherfolk livelihood, and food security.

From Metro Manila to further south in the Visayan provinces, proponents of reclamation projects share optimism for urban development. However, such visions of development exclude the plight of coastal communities and environmental groups. To bridge this gap, experts continue to call for amendments in existing land reclamation policies to avoid undervaluing life at present in favor of potential economic gains.