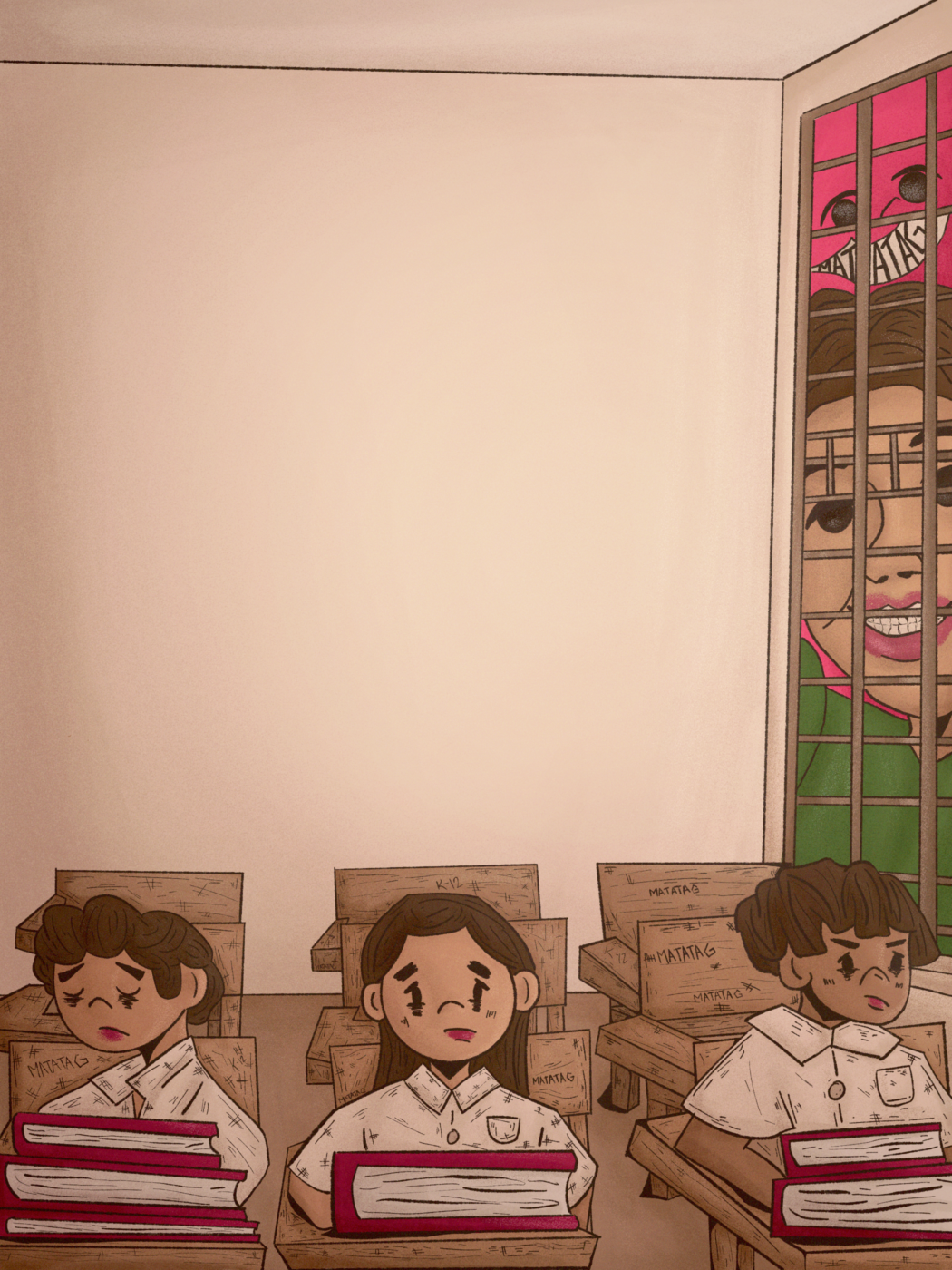

WHILE THE nation continues to grapple with the aftermath of the pandemic, the Marcos-Duterte administration has chosen to embark on yet another experimental educational scheme—the MATATAG Curriculum. Claimed by President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. to be the “best education system yet” in the country, the MATATAG curriculum: Bansang Makabata, Batang Makabansa aims to decongest the present K-12 system. The plan aims to achieve its goals by reducing learning competencies, emphasizing foundational skills, and embedding peace competencies in learners beginning kindergarten to Grade 3.

With its pilot implementation officially conducted last September, the new curriculum has generated mixed opinions among educators. Its timing is to be questioned, especially in light of the challenges faced during the pandemic and the ongoing transition back to onsite learning for both teachers and students.

The introduction of the MATATAG curriculum is a testament to the worrying lack of priority in addressing the root causes of the country’s educational crisis. These issues include classroom and faculty shortages, teachers’ long-term demands for salary increases, and the lack and mismanagement of funding, among many others.

False promise

Efforts to change the education system are nothing new for this generation of students. Last 2012, the Aquino administration introduced the “K-to-12 Curriculum,” which added a total of three years to the originally ten-year-long basic education program in the country. The change established a “universal kindergarten” and added two years of senior high school to make Filipino students “more globally competitive.”

In defense of this major reform, former president Benigno Aquino III cited experiences of Filipinos abroad who found it difficult to attain jobs with the original ten-year program. Until the introduction of the current curriculum, the Philippines was the only country in Asia and one out of three worldwide to have a 10-year basic education cycle.

Along with increasing global competitiveness, the curriculum aimed to provide sufficient time for students to master learning, striving to develop citizens who are equipped with both learning and employment competencies. This reform was heavily framed as a solution to the employment issues in the country, promising that students could join the workforce as soon as they graduated senior high school.

Many progressive groups at the time argued that the new changes would not only worsen existing issues, but also perpetuate a system that exploits cheap labor. The normalization of such a phenomenon reflects the distressing impact of generational poverty and systemic inequalities in our country. Until the government acknowledges the interconnectedness of such issues, the reforms it introduces continue to be inadequate solutions.

A decade after the K-12 implementation, a Social Weather Stations (SWS) poll revealed that 50% of Filipino adults are dissatisfied with the K-12 curriculum, calling the additional years “a waste of time.” Many individuals remarked that the K-12 did not accomplish its goal of shaping job-ready graduates—one of the program’s promises.

Teacher groups such as the Alliance of Concerned Teachers (ACT) also mentioned that the change did exactly what progressive groups feared—it managed to magnify the educational crisis even further. Classroom and teacher shortages worsened, and a lack of coordination between the Department of Education (DepEd) and the Commission of Higher Education persisted, betraying the aspirations of the youth who were promised bright futures.

Solution or facade

In light of the aforementioned concerns, the newly introduced MATATAG curriculum revises the K-10 program by ‘decongesting’ it. This program will reduce the number of learning competencies from over 11,000 to 3,600. It will remove subjects including mother tongue, while increasing the focus on foundational skills such as literacy, numeracy, and socio-emotional skills. It also introduces a new learning area—good manners and right conduct.

Similar to the K-12 curriculum, one of the main competencies of the MATATAG curriculum is the promise to make Filipinos job-ready without needing a college degree. Alongside Marcos Jr., Vice President and Education Secretary Sara Duterte places heavy hope in the revisions’ potential to address the current issues of the education system.

However, the MATATAG curriculum has been heavily criticized, with ACT calling it “premature.” They express that the revision of K-10 is as problematic as the K-12 curriculum, as it fails to truly address the roots of the education crisis. ACT asserts that without a proper budget to support plans for the education sector, the new K-10 curriculum will receive the same fate as K-12.

Despite worsened classroom and teacher shortages after the pandemic, DepEd only received a 5% increase for 2024. Notably included in this budget is Duterte’s 150 million pesos confidential fund, which could have been better allocated to the mentioned shortages. These actions raise questions about the sincerity of their efforts and their bold promises to fix the education system within their term.

Apart from these concerns, multiple teacher groups have called out DepEd for using the MATATAG curriculum to distort history—whitewashing the image of the late Ferdinand Marcos Sr. as a dictator.

With concerns about proper implementation, clashing political interests, and the worsening of learning poverty in the Philippines, introducing new revisions to the curriculum will have lasting effects on students and the future of the education system.

For the youth

Evidently, the government increasingly needs to lend ears to its harshest critics to truly alleviate the country’s educational crisis. They must also persistently prove that education remains a top priority of the state by increasing its budget, addressing infrastructure and faculty shortages, and strengthening connections with stakeholders such as teacher groups through consultations. A holistic and participatory approach to implementing educational reforms is needed to ensure that long-standing issues will not be exacerbated.

The success of these efforts hinges on the government’s genuine alignment with the sector’s educational needs and concerns, including the imperative of presenting a truthful telling of our country’s history. Rather than prioritizing global competition and expanding the transnational workforce, the government should deepen its goals to include fostering a more nationalistic and mass-oriented education.

After all, if the goal is to craft reforms in the interest of the hope of the nation—its students—then these changes should not be driven by concealed political agendas under the guise of “progressive” programs. In the aftermath of the pandemic, to fail these students another time is to waste the potential of our country’s next generation of nation-builders.