The rich biodiversities of Ateneo and UP Diliman have silently shielded Quezon City from climate change, but rapid development may be depleting the city’s remaining lungs.

AFTER A day’s worth of exams, Darlene Ranoco (3 AB IS) unwinds in front of the Church of the Gesù. Sitting there, she finds solace in the peaks of sunset seeping through the skyline of buildings and washing over Bellarmine Field.

Not too long ago, the view of the sunset in the Ateneo de Manila University was much more ideal. If one sits at the right building at the right time, they can watch the sun descend as far as the Manila Bay horizon.

Time, however, has turned Quezon City into a concrete jungle, with green spaces dwindling over the years. The campuses of the Ateneo and the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman campuses are among these green spaces.

However, rising demand for built structures threatens both campuses’ green spaces—the city’s frontliners in the battle against rising heat, excessive flooding, and extreme weather events.

Taking up the shield

Ranoco, born and raised in Cebu, felt the heat almost immediately when she arrived in Manila for college. “I can feel the light prick at my skin here more,” Ranoco says.

A 2020 study supports her experience. While heat indices in Cebu have increased, all 11 cities that reported very high heat hazard indices were found in Metro Manila.

Heat indices—also known as “feels-like” temperatures—measure air temperature and relative humidity to estimate how hot it feels on the human body.

However, Ranoco claims that she feels cooler inside the Ateneo than the rest of the city.

A 2019 study assessed the number of barangays affected by the urban heat island (UHI) effect in Quezon City. This phenomenon happens when cities experience warmer temperatures than nearby rural areas due to the conversion of vegetation into impervious surfaces that absorb and trap heat. This is expected to worsen as the overall climate continues to warm.

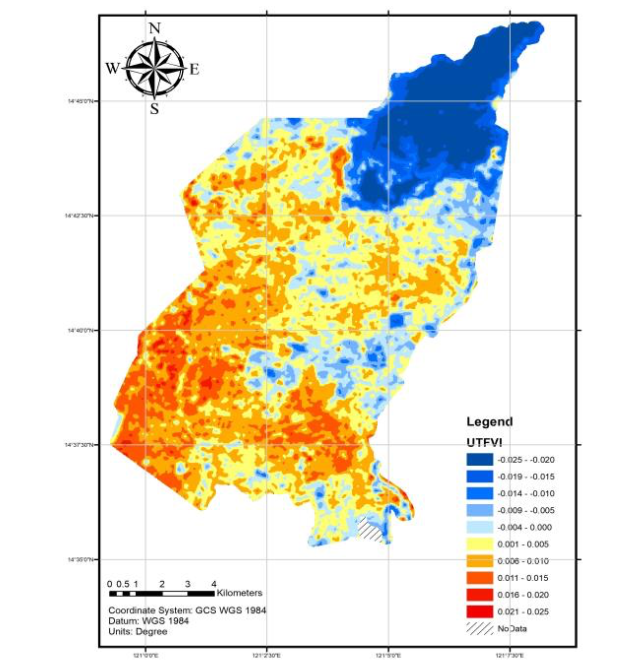

A map illustrating the extent of the UHI effect in Quezon City showed the northernmost region at the foothills of the Sierra Madre in blue remained cool. Curiously, the central-eastern barangays, including those surrounding UP Campus and Loyola Heights, had the lowest UHI strength despite the tens of thousands of students entering its major universities every day.

The study concluded that industrial and commercial lands—typically in the southwestern region of Quezon City—were more prone to UHI effects, while agricultural and aquatic lands in the city’s northern region were less prone. These two universities, paired with the presence of Quezon Memorial Circle and Ninoy Aquino Park, likely lower the central-eastern barangays’ temperatures by having enough green spaces.

Ninety-two hectares of UP’s 500-hectare land are natural spaces: forests, wetlands, swamps, and grasslands. It also houses the UP Arboretum, a 16-hectare man-made rainforest that is the home of 9,000 tropical plants and 77 unique species—most of which are endangered.

The Ateneo, on the other hand, dedicates half of their 90-hectare land to green and open spaces. They, too, have an arboretum of their own, with 101 endemic Philippine trees growing behind their dormitories.

“The vegetation we have on campus helps shield us from the heat,” discusses Ateneo Institute of Sustainability Program Director Abigail Favis. Since 2016, the Ateneo has refrained from using concrete for paving their roads due to the material’s tendency to absorb and reflect heat and light more than soil and vegetation, trapping more hot air on the school grounds.

The move has left some Ateneans complaining about mud on their shoes during the rainy season. Favis, however, sees this as a small sacrifice to make to prevent a greater inconvenience: urban flooding.

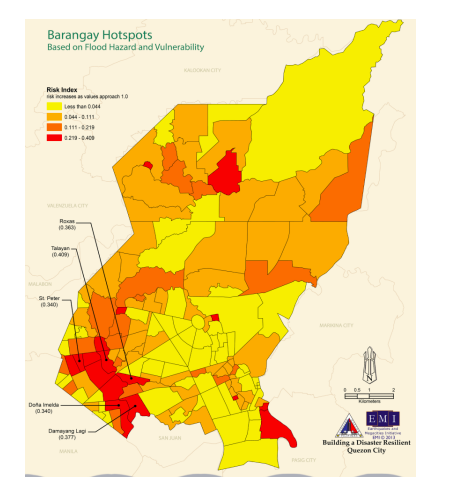

Quezon City is flood-prone despite being more elevated than other cities in Metro Manila, largely because it is the catchment area of five river systems. Barangays closer to Ateneo and Diliman (with the exception of one), however, were less vulnerable to flooding as compared to other areas, according to a risk assessment of the area.

UP Diliman Ecology Instructor Jelaine Gan believes that a part of this has to do with the road structures in their campus.

During the onslaught of Typhoon Ondoy in 2009, Quezon City was among the most flooded areas in Metro Manila, with floods reaching up to neck level. Gan claims that it would have been much worse had a depressed road in UP not acted as a catch basin.

“The University Avenue was filled,” Gan recalls. “Without it, the water would have flooded other parts of Manila.”

The vegetated lands in these two campuses also absorb rainwater, not only preventing floods but also providing rainwater irrigation systems.

But typhoons have gotten much worse since 2009 as sea temperatures and levels continue to rise. The Philippines is growing ever more vulnerable to this.

The worsening effects of the climate crisis have not stopped cities from rapidly urbanizing, which both Favis and Gan see as detrimental if the environment is sacrificed to achieve it.

To build or not to build?

In 2020, the UP Board of Regents controversially lifted the protected status of the UP Arboretum to establish the UP-Philippine General Hospital (UP-PGH) for cancer research. The build will claim nearly ten of the arboretum’s 16 hectares and displace 650 informal settler families. Students, faculty, and environmentalists alike protested the move.

“There’s always going to be a fight for space,” Gan says. “Always, there’s going to be the question of [whether] to build or not to build in these green spaces.”

The conversation about land usually revolves around whether it is productive or idle. Gan believes there is no such thing as the latter. “These ‘idle’ lands are actually very productive. These are our safeguards and resilient points, allowing us to withstand floods and climate change effects,” she mentions.

The UP Arboretum has been productive ever since the Spanish period when the Jesuits owned an estate on its land. When the Philippines gained independence, the title was passed to the Philippine government and UP. The area was ideal for an arboretum: the soil was rich, the land was elevated, natural waterways were occurring, and there were a few fruit-bearing trees with wildlife. For 75 years, the UP Arboretum has been a sanctuary of diverse and endangered wildlife and tree species.

Universities try to build around already existing flora as much as they can. In Diliman, there is always an easement between water bodies and built structures, like how the man-made lagoon still has leeway for wildlife or how the buildings are used as bat roosts. UP Diliman’s Biodiversity Handbook highlights this ecological integrity between built and natural environments multiple times.

There are many examples of this in the Ateneo as well. The curved U-shape of the Gonzaga Hall and Science Education Complex Walk intersection is not just a design choice but a practical one: to preserve an old Narra tree that has been with the Ateneo for decades.

There are committees and teams focused on identifying green spaces within campus that are forbidden, but not all of their words are heeded.

“There is always conflict between preservation and development in the traditional sense,” Gan says. “Every time you make construction there’s always going to be [an] impact from that. You are taking over a green space and displacing wildlife.”

The UP-PGH construction will reverse the years’ worth of work to maintain the ambient temperature and water table around the area, making it vulnerable to heat exposure and flooding.

Environmentalists are fighting hard to junk this project, but it seems to be charging full steam ahead. Early this year, the UP-PGH became the first public-private partnership project approved by the President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. administration.

Collective action

Favis considers the conflict between preservation and development a “complex and wicked problem.” However, she points out the power of collective action towards a focused and specific goal.

One example of this was how Ateneans fought against a road extension and widening project that would have cut down a portion of the SOM Forest in 2019. Faculty, students, and staff, pushed back by citing data to support their stand, and quickly organizing to petition the administration to stop the project. Today, the entire stretch of the SOM Forest breathes on.

The fight to preserve the city’s last remaining green zones, however, is far from over. Environmentalists are constantly finding new, innovative ways to keep campus biodiversity alive amid the demand for more built structures.

Favis and Gan are not strangers to each other. They both created The UP Wild and The Ateneo Wild respectively, social media campaigns that educate the public on the wildlife and ecosystems in their campuses.

Ranoco follows both pages. She also plays an active role in the social media presence of Ateneans Guided and Inspired by Our Love for Animals (AGILA), a student-led organization fighting to preserve campus biodiversity and wildlife. Last October, Ranoco and her fellow AGILA members created an explainer introducing Ateneans to the country’s rich biodiversity and the key roles they have in both its destruction and preservation.

Favis underscored the important role students have in preserving the biodiversity of their campuses and cities.

“Even when you’re in the city, [you] expose yourself to nature. […] Whether or not we realize it, we will always have a bond to the natural world. In order for us to develop as a society, we have to see nature as our friend, not our enemy,” the environmentalist says.

This story was supported by Climate Tracker Asia and the U.S. Embassy in the Philippines.