“I literally froze. I know what to do, but fear got the better of me.”

What began as a normal history class on the second floor of Bellarmine Hall soon became a moment of panic for Gian Marquez (3 BS ES) when an intensity IV earthquake was felt in Quezon City last June 15.

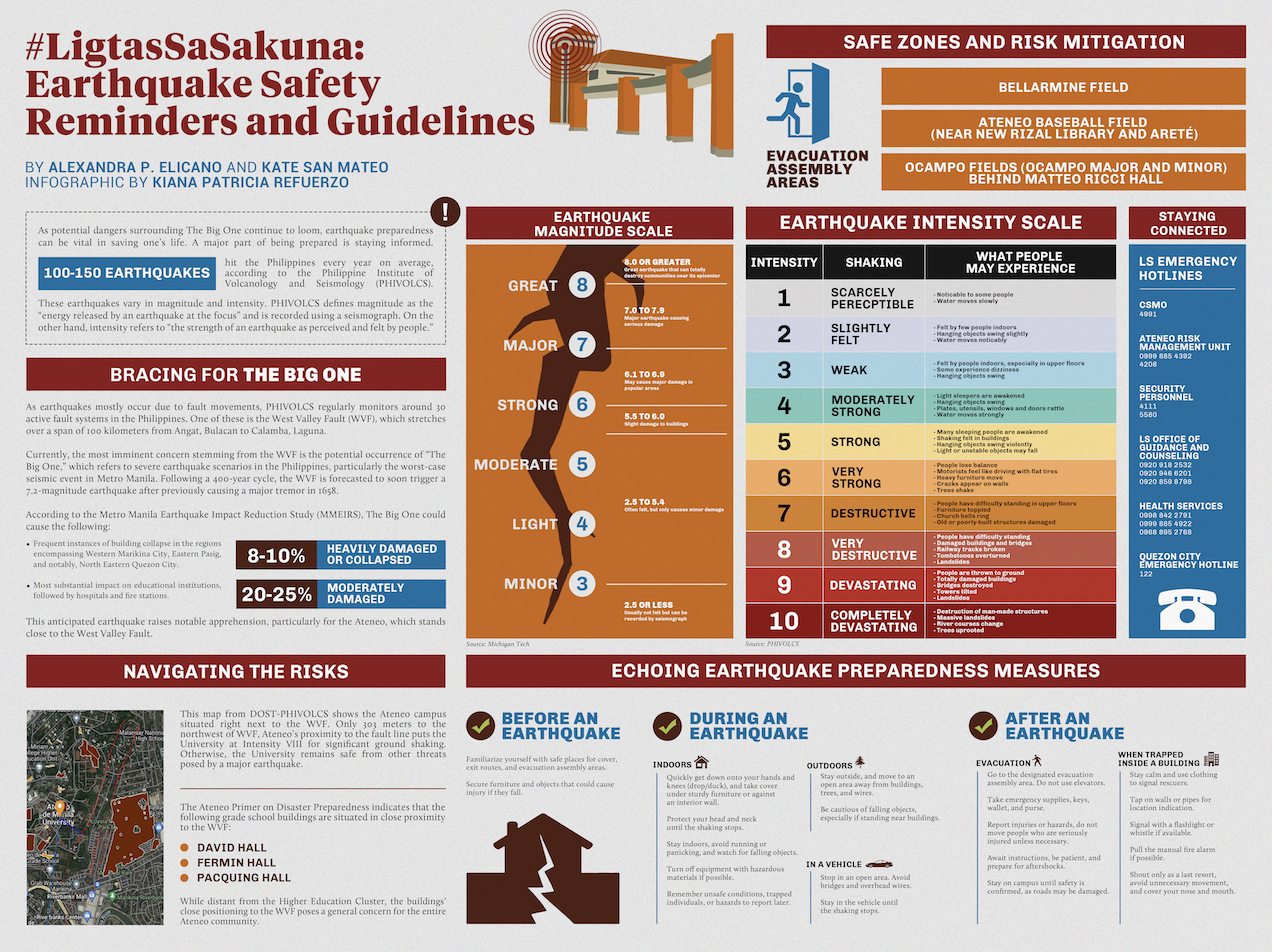

On the Ateneo grounds, everyone experienced the earthquake differently. Marquez recalled seeing the projector shaking before feeling a swinging sensation, which fit the description for a moderately strong intensity earthquake on the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) Earthquake Intensity Scale.

As of writing, 94 earthquakes classified as moderate to major hit different parts of the Philippines beginning in mid-June, with recorded magnitudes ranging from 4.0 to 6.3.

These recent earthquakes, coupled with fears surrounding the imminent dangers posed by The Big One, strengthen students’ call for increased efforts in building a disaster-resilient Ateneo community.

No sense of urgency

Boosting its disaster preparedness initiatives, the University held emergency drills for Grade School and Junior High School early this year. However, undergraduate students from the Higher Education Cluster (HEC) have yet to experience such efforts since the return of onsite classes.

When asked about his own earthquake preparedness, Marquez admitted feeling “nowhere near confident” especially without undergoing any drills and training sessions conducted by the University. He was also unaware of the specific evacuation assembly areas on campus.

While this calls for effective, constant communication between the administration and the whole Ateneo community, being well-informed alone does not ensure disaster preparedness.

Despite knowing exactly what to do when an earthquake hits, Marquez found himself unable to move due to the shock. There was also no automatic response nor reaction from his instructor and other classmates at the time.

In these moments of emergencies, Marquez emphasized the need for disaster preparedness training, not only for students but also for the whole Ateneo workforce. According to him, training and seminars would help faculty and other employees “relay information to students and proactively react to the situation” in case of an earthquake.

However, apart from conducting extensive preparations for emergencies, examining students’ perceptions and attitudes toward disaster preparedness is also crucial. Students seem to display a lacking sense of urgency, as observed among Ateneans leaving the campus before fire and earthquake drills and some students making a TikTok video during the actual June 15 earthquake evacuation.

Marquez finds this passive attitude beyond alarming. “It seems like the occurrence of natural disasters [is] being attributed by students for class suspension. […] There [really] is no sense of urgency anymore to everyone,” he says.

Reevaluating structural resilience

While University members are encouraged to commit themselves to safety procedures, the Central Facilities and Management Office (CFMO), together with the Local Unit Emergency Response Team (LUERT), undertakes a crucial responsibility in evaluating the seismic vulnerability and structural integrity of campus buildings.

Following the June 15 earthquake, CFMO Director Michael Canlas shares that they conducted an inspection of the campus for possible building cracks and deformities. He adds that the unit’s Post Construction and Building Care section ensures that campus facilities are monitored and thoroughly assessed to determine the necessary interventions.

Canlas notes that the University’s recent architectural projects, as well as its forthcoming construction undertakings, adhere to the guidelines specified in the National Structural Code of the Philippines. This compliance to established regulatory principles guarantees the structures’ integrity and their capacity to withstand seismic events.

Meanwhile, older buildings undergo retrofitting measures based on CFMO’s findings from inspection and examination. These efforts are done in recognition of the close proximity of certain areas on campus to the West Valley Fault (WVF), where The Big One is forecasted to originate.

As highlighted in the Ateneo Primer on Disaster Preparedness, three grade school buildings—specifically David Hall, Fermin Hall, and Pacquing Hall—stand close to the WVF. While these structures are distant from the HEC, their adjacency to the fault line raises concerns for the entire Ateneo community.

According to Canlas, the Campus Safety and Mobility Office (CSMO) collaborates with the school units and conducts two emergency drills per year, encompassing both unit-wide and University-wide exercises. It also engages in the post-drill evaluation and solicits feedback from LUERT members and the Building Emergency Assistance Team.

To assess the Ateneo’s readiness for earthquakes, LUERT head Christopher Castillo shares that they measure the speed of University members in evacuating the building and reaching emergency assembly areas, which are the Bellarmine Field, the Ateneo Baseball Field, and the major and minor Ocampo Fields.

On the other hand, Canlas points out the importance of referring to classroom posters displaying earthquake response procedures, such as the “duck, cover, and hold” technique. However, he admits that these posters have to be updated due to changes in hotline numbers.

Expanding upon this, the LUERT plans to develop instructional videos or use social media platforms to communicate basic emergency response protocols, although doing so may require the active involvement of some central offices.

Shared responsibility

As seismic risks persist, the need for a better-coordinated effort among the Ateneo community becomes even more apparent.

Marquez urges the administration to conduct more drills as an avenue where students can apply what they already know. “Train them, instill a culture of urgency and responsiveness to them.[…] Have them be prepared during [disaster and emergency] scenarios,” he says.

Meanwhile, Canlas states that the University constantly updates its disaster preparedness plans by coordinating with agencies such as the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority, the Bureau of Fire Protection, and the Barangay Response Team. The CSMO also partners with the Ateneo Institute of Sustainability in improving safety guidelines and organizing disaster-related workshops.

Following this, Castillo recognizes the influence and network of student groups as effective channels for disseminating crucial information to their peers. He underscores the shared duty of the administration and various organizations to guarantee each other’s well-being.

“The advocacy here is for people to be not dependent on external prompting on how to be safe. Each one has a responsibility to keep oneself safe and those within reach,” Castillo asserts.

Similarly, Marquez prompts Ateneo student organizations to do their part and spearhead localized disaster preparedness initiatives, such as information drives and disaster response training. “We really don’t know when disasters will happen so it really boils down [on] how prepared [we] are,” he reiterates.

As earthquakes remain unpredictable, the safety of the Ateneo community lies in the institution’s consistent and extensive preparations. Thus, effective systems and improved coordination within the University are essential in securing an unshaken hill.