Graffiti is a powerful tool for voicing dissent in public spaces—but when the lines between “artist” and “vandal” grow blurry, debates emerge about its moral ramifications.

ZIP THROUGH EDSA’s busy roads and you will catch vibrantly colored murals celebrating women empowerment—a visual feast for the 7:00 AM rush hour. Turn to a narrow eskinita and you will spot the words “NEVER AGAIN” spray-painted in rushed handwriting.

These forms of street art or graffiti are characteristic of a modern city. Such kinds of art in these public, urbanized spheres do not adhere to a single technique, style, or method, which can be attributed to the socioeconomic diversity inherent to large cities.

Different strokes

To categorize graffiti as belonging to high or low art is not too simple. Based on his undergraduate Fine Arts thesis on the practice of graffiti, Antares Bartolome argues that these labels are relative to one’s socioeconomic status.

“The dynamic of high and low art relies on the forces at play within the struggle for power. The term ‘art,’ when you attach it to something, already carries the connotation that it is of value and [thus] worth pursuing. […] Those different assertions of how it is defined inform that struggle,” he explains.

From the perspective of a practitioner, street artist Archie Oclos espouses similar sentiments on the privilege inherent to these labels. He posits that the usual evaluation of high and low art is dependent on one’s education status or the lack thereof.

Institutions in power control what art is “good” and palatable. The inherent form and distribution of graffiti constructs an unruly and dirty image often associated with resistance. Graffiti, for instance, may encroach on private property—a valuable asset in a capitalist society—further contributing to its bastardized reputation.

As evidence of this, “street art” and “graffiti”—though existing on the same plane—both carry different connotations. The former is applied to artists who have access to legitimate spaces, but if one’s art fails to afford this privilege, their work is demoted to “graffiti” or even “vandalism.”

Moreover, Oclos challenges the status quo of who should define art. “Who are we to say kung ang high art lang ang tanggap na art, or ang low art ay ‘di tanggap na art (Who are we to say that high art is the only acceptable art, or that low art is not acceptable)?” he asks.

The artist as the protester

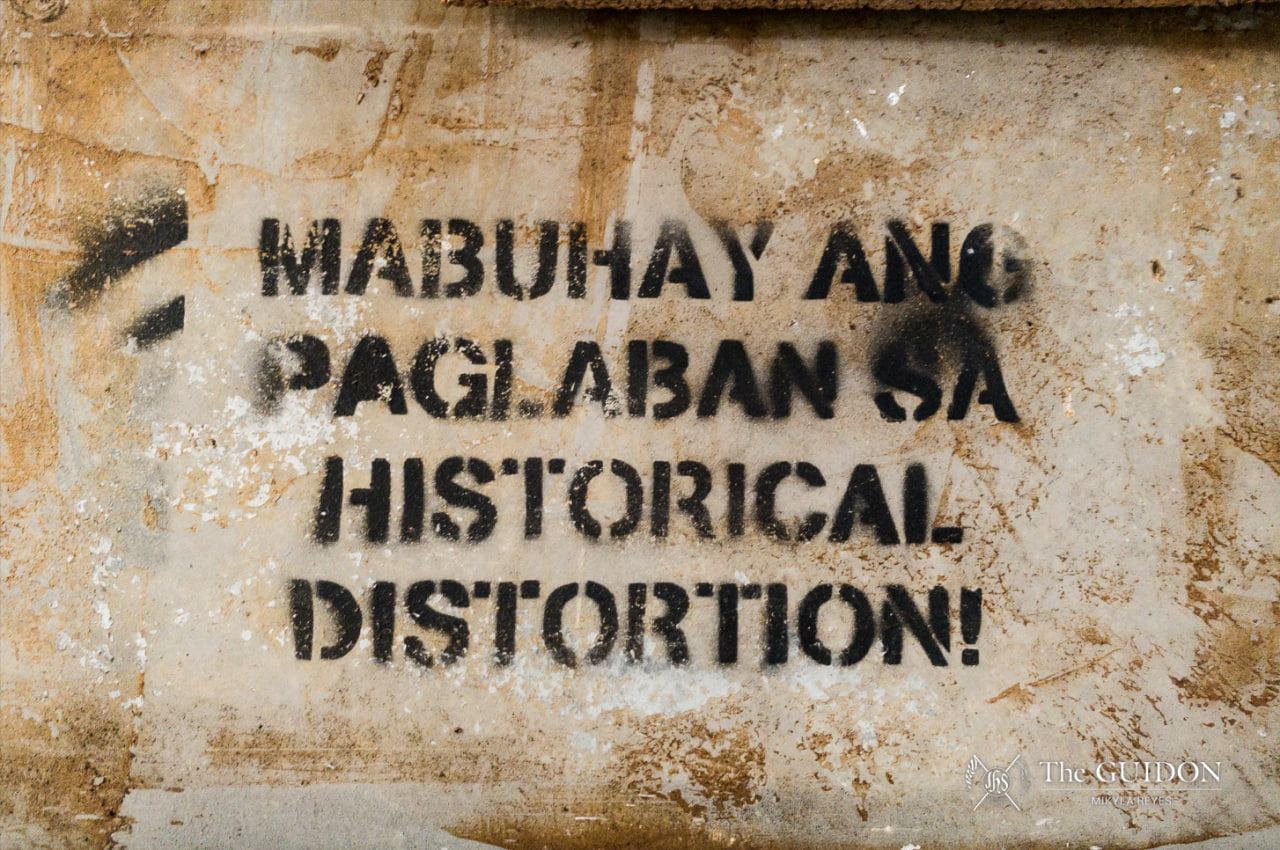

While conventional art often finds itself confined within the borders of galleries and elite circles, graffiti is the unfiltered expression of the marginalized. This artistic rebellion finds resonance in history when the early Marcos regime weaponized art to beautify the Philippines and hide the horrific injustices under the shadow of extravagance. As Bartolome explains, they strategically championed formalist art because of its detachment from the visible, political world.

The Marcoses did not only collect art—they were determined to make the Philippines an art piece itself through grand edifices fostering exclusivity. Imelda Marcos’s fixation on beauty led her to deem the squatters across the Manila International Airport (renamed Ninoy Aquino International Airport) an “eyesore,” ordering that their homes be demolished to hide the poverty from freshly landed tourists.

With censorship at an all-time high and the press constantly monitored, street art became a manifestation of society’s struggles and cries. “By large, street art is born out of a need for another platform to express yourself,” Bartolome explains.

Amid the Marcoses’ efforts in silencing the masses, the Nagkakaisang Progresibong Artista at Arkitekto ’71 (NPAA ’71) stood as one of the pioneering organizations of militant artists from diverse fine arts colleges. The dangers of operating in secret during the Marcos regime did not stop them from finding an outlet for political protest through street art.

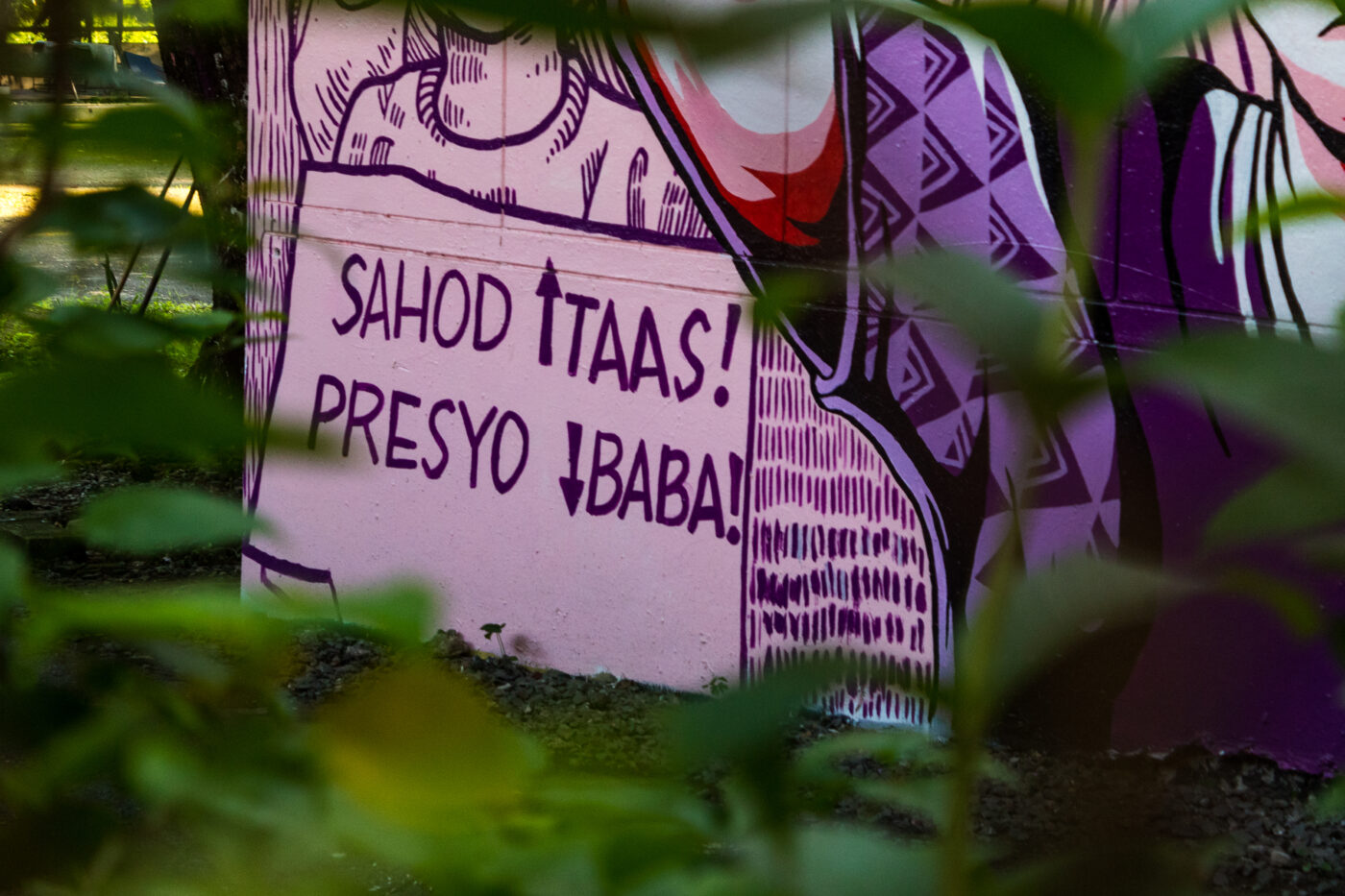

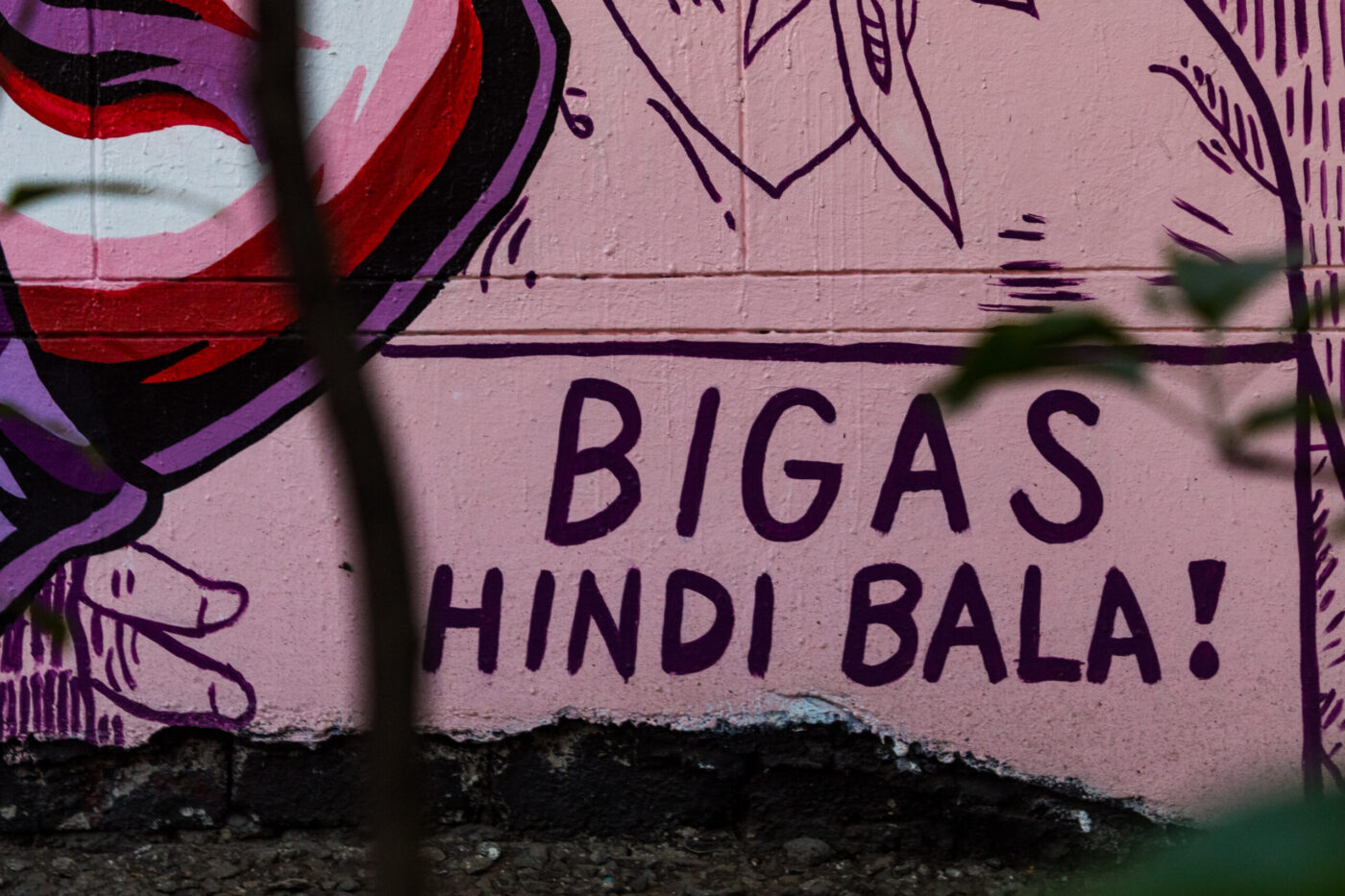

In today’s political climate, street art persists as a platform for untold and undocumented struggles. Having worked with indigenous peoples, Oclos asserts that these different stories must be told. “‘Yung kuwentong lokal at katutubo, laging nakukuwento sa pamamaraan [ng] turismo. ‘Yung totoo, hindi naman ganyan ang kalagayan ng taong ‘yun (The local stories of the Filipino people are always narrated through the lens of tourism. The truth is, the situation is not really as picturesque as that),” Oclos expresses.

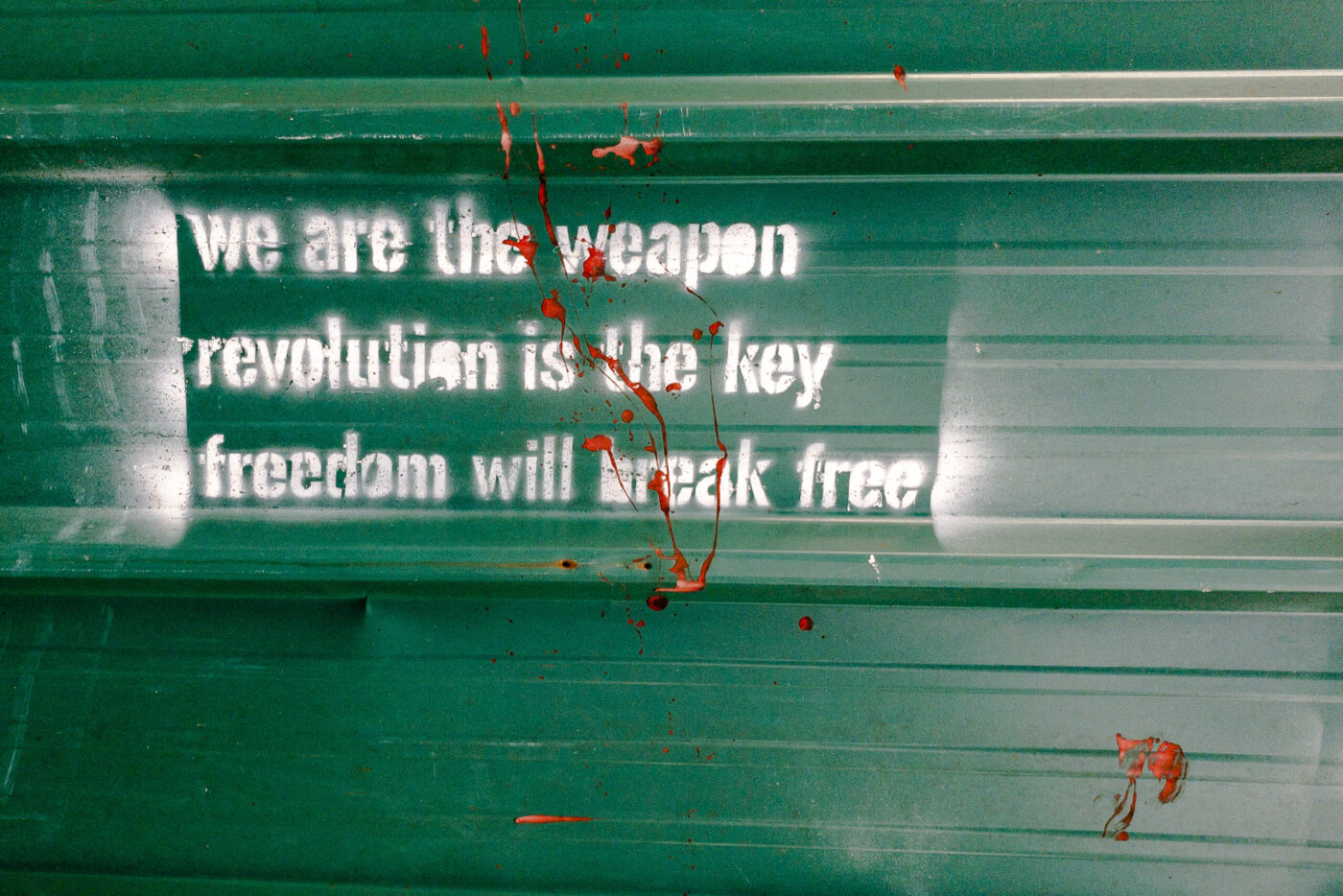

However, street artists continue to battle repression from state forces. In 2019, policemen dressed in civilian clothing manhandled, beat up, and arrested four members of youth organization Panday Sining for “vandalism.” These artists had painted the Lagusnilad Underpass of Manila with the words “Digmang bayan sagot sa martial law – PS” (Revolution is the answer to martial law – PS) and “Atin ang Pinas! US-China layas! – PS” (The Philippines is ours! US-China leave! – PS) in red. This instance highlights the government’s unapologetic dismissal of street art in lieu of maintaining a clean and beautiful public space.

Bartolome and Oclos state that even if the messages of street art remain relevant, it will be perceived as illegal when done on government spaces or private property. However, instead of fixating on its criminality, they put emphasis on understanding why such practices are coming to light. “Vandals are a reflection of a failed society,” Oclos says.

Taking art to the streets

Art cannot exist independently of its socio-political ecology. As a product of its time and place, art and its value are often tied to the broader circumstances that shape its creation. In the battlefield for truth and justice, street art reflective of the gritty realities strives to upend the Marcoses’ narrative of a “beautiful” Philippines.

With the second year of the Marcos-Duterte tandem, the urgency for protest has reached its zenith, fueled by the surge of historical revision and political corruption. “We have to utilize everything, from graffiti to publishing, to everything while we have it. As soon as something pops up and they clamp on it, we have to find another way,” Bartolome says.

Despite the backlash and criminalization it faces, street art undeniably democratizes physical spaces. In these communal sites, people can freely express their anger and disillusionment against the government that has failed them time and time again. Street art revolutionizes society not just by challenging our evaluation of high versus low art, but also by reclaiming the streets and bringing it closer to the public—with whom it truly belongs.