In the face of modernity’s unceasing tides, indigenous cultures tend to get left behind as development centers on the select few. Thus, community-based efforts continue to sprout, aiming to safeguard the rights of indigenous peoples and their cultures.

WHEN DISCUSSIONS on development are centralized on dominant authorities, the voices of indigenous peoples (IPs) are drowned out in favor of more powerful figures in policy-making. Indigenous cultures, in return, have begun to slowly fade from national consciousness—despite living in a country that is home to diverse ethnolinguistic groups.

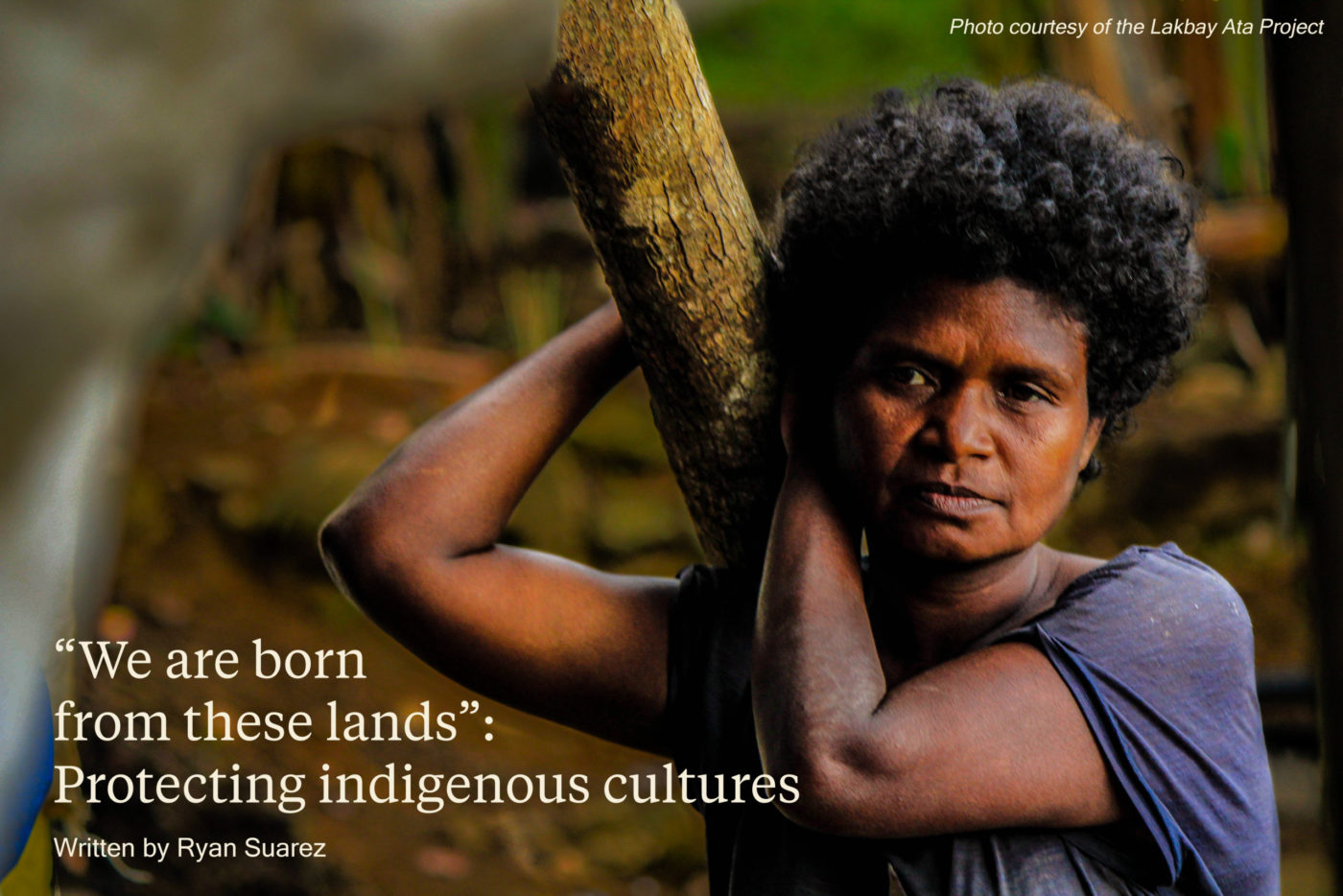

Juxtaposed in a society hurtling towards globalized notions of modernity, the Ata tribe of Don Salvador Benedicto goes against the tide by holding on to the thinning threads of treasured tradition. However, the task at hand proves challenging to continue, especially for the tribe: When one has to deal with problems of acquiring basic entitlements, active efforts towards cultural preservation move down the priority list.

Kabiyugan (Family)

Nestled in the mountainous areas of Negros Occidental, the Ata community carries with them a rich past. Local history documents them as the original settlers of the island, having even interacted with the Spaniards. However, residents of the surrounding lowlands know little about the tribe, even confusing them with other indigenous groups such as the Aeta or the Ati. Sheila Uy, PhD, who spearheads the IP Education Program of the University of Saint La Salle (USLS), emphasizes that the Ata are not given much attention in their own province. “It’s very disheartening that [their legacy is] not part of our valuation of local history,” she shares.

The problem extends to the community’s language, formally known as Inata. Labeled by the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino in 2019 as an “endangered language,” Inata has seen a sharp decrease in its usage over time. Jaquelyn Velez, the only Ata currently enrolled in the USLS, laments that the language has not been passed down to the children of the tribe. “Maliit lang alam ko (What I know is little). Our language is not taught. It’s not transferred to us, the Ata children and youth. The language is only known by the elders,” she stresses.

Both Velez and Uy note that assimilation to the “mainstream culture” in the public school system and other social groups has been one of the primary causes in the diminishing prevalence of the language. “Even if the language is spoken at home, the kids spend more time at school, [where] the curriculum is not taught in the [Inata] language,” Uy elucidates.

The lack of representation and reproduction of local knowledge in the educational curriculum has slowly chipped away at the foundations of their cultural identity.

Moreover, the Ata tribe suffer more pressing issues that affect their daily lives, such as the inaccessibility of basic needs. Students have to walk nearly two to three hours just to attend classes. The nearest healthcare facility—which Velez describes as a small health center—is also distant from the tribe’s village.

Selling their agricultural produce is also arduous for the tribe, with the lack of farm-to-market roads and government support. Noting these hindrances, Uy adds that the Ata become forced to sell these products at drastically low prices.

“They wouldn’t think about [preserving their language] because the very problem they’re encountering is how to eat even once a day, how to find a job, to live…. For them, Inata is not a means anymore to survive. They have to speak the language of [other] people for them to survive,” Uy shares. These experiences have led the Ata to feel that their culture and identity hold minimal value, especially to their notion of personal development.

Tabangan (Cooperation)

As a response to the slowly fading cultural identity of the Ata, the USLS College of Education established the Lakbay Ata Project in 2019. The initiative aims to empower the Ata as well as raise awareness and sensitivity about their situation. Through drafting and implementing a comprehensive IP education curriculum, Uy hopes that the project would help the Ata children rebuild their cultural identities.

The project finds its roots in research studies conducted by the College as early as 2010, with direct engagements subsequently commencing in 2017. Uy states that Velez’s older sister, Vejiel, paved the way for stronger community engagements, as she had been the first known Ata to study in the University. These developments enabled the College to collect information on the values, practices, and history of the tribe. “The research we conducted has capacitated us to share and use the resources on contextualizing the K-12 curriculum to the indigenous knowledge and practices,” Uy explains.

The success of the initiative has also encouraged more external stakeholders to participate in building solutions for the Ata. For instance, the Ata chieftain has been in coordination with an IP committee in the local government unit. The mayor of Don Salvador Benedicto, upon communication with the Lakbay Ata Project, has also become supportive of their project management and implementation. As a volunteer-based unfunded project, the organization values support from these local actors.

However, the community still faces harsh realities outside the scope of the Lakbay Ata Project’s capabilities. Uy expresses that the comprehensive stipulations of the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act of 1997 are not fully realized. “When it comes to political empowerment, like giving them voices for local legislation, I don’t think there is that kind of opportunity,” Uy explains. She further laments that even if an Ata runs for office, winning at the local level is a hundred-to-one shot.

The Ata are also constantly burdened with the lack of cooperation from government agencies that are supposedly tasked to safeguard their rights and support their development. Velez claims that the regional office of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples does not heed their invites to meetings and discussions. Thus, even as the tribe stakes a claim to 200 hectares of ancestral domain, they have yet to receive their Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title—a document that formally recognizes their ownership of the land.

As the tribe has no certification for their ownership of the land, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources has cordoned off some of their ancestral domain as environmentally protected areas. This prevented them from obtaining food, especially as the Ata people are traditional foragers and hunter-gatherers.

Velez adds that among her community’s dreams is to achieve their right to their ancestral domain. “We really believe that that is our life…. We are fighting because we are born from these lands,” she expresses.

Ikapuyo (Tomorrow)

Amid these compounding socio-political issues, much emphasis is placed on the power of collective action—especially from initiatives of external stakeholders. “We cannot move alone,” Velez firmly asserts.

Nevertheless, promising achievements and budding practices continue to arise from community-coordinated efforts such as the Lakbay Ata Project. The quest to champion IP education stems from a genuine desire to forward sustainable contextualized development. In the case of the Ata and many other IPs, this is development that treasures cultural identity and history as tools for greater empowerment.

The community insists that these endeavors should not stop at the local level. The severe poverty and social exclusion that the Ata and other IP communities experience are deep-rooted issues that can only be solved through intensive national interventions.

The voices of these communities should be listened to, not just with the policies and projects that affect them, but also in discussions of nation-building and development. “We are also part of the country. We are part of the Philippines,” Velez declares.