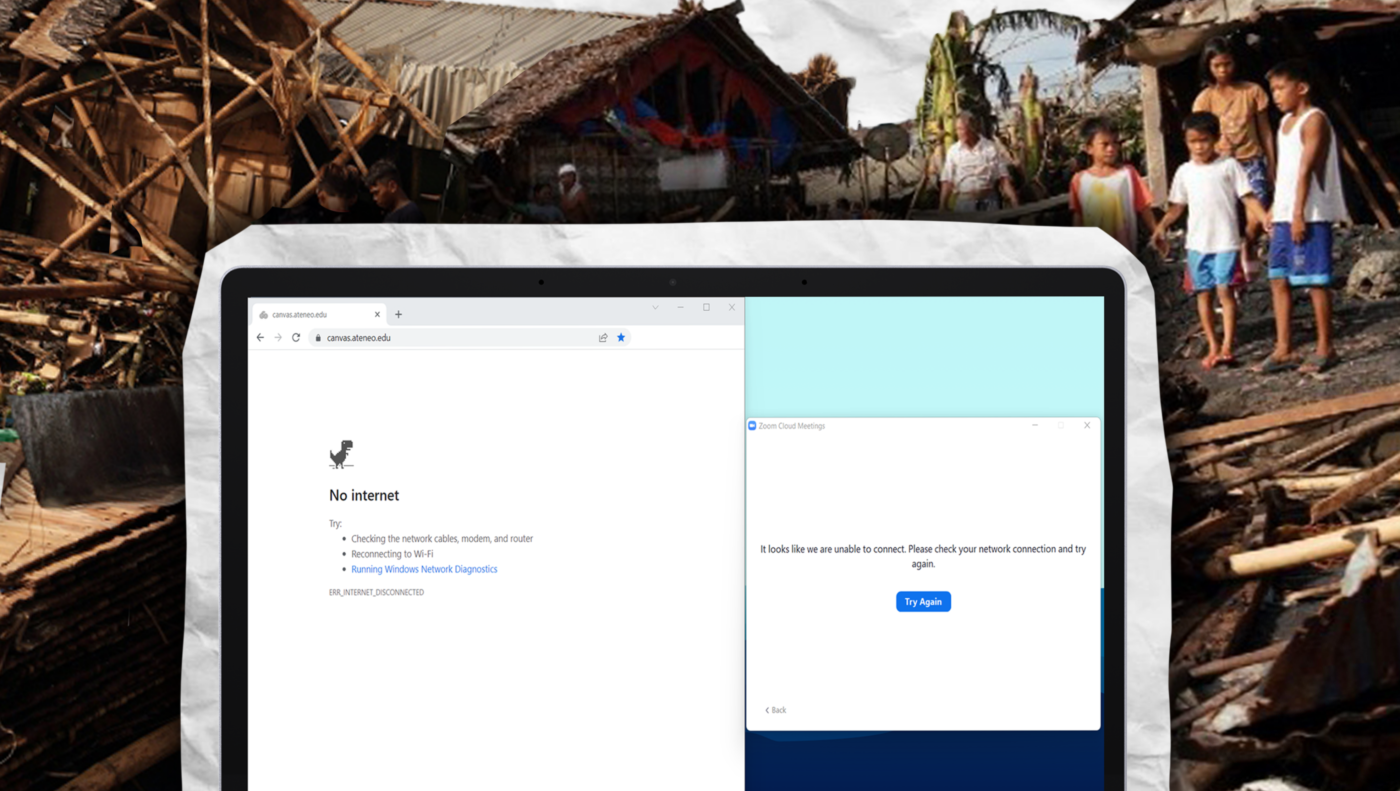

WHILE EVERYONE braced themselves for the worst that Typhoon Odette could bring—violent winds, torrential rains, and raging floods—several Ateneans were adamant to stay put, hunkered down with their laptops to submit their final exams. Thus, alongside the flashing notifications of their impending deadlines were their windows creaking from the wind, their houses seeping with floodwater, and the darkness looming in the sky above.

Nearly three months after Typhoon Odette’s landfall, Ateneans are still grappling with its parallel storm, as they contend with the deep emotional scars and overwhelming academic backlog that Typhoon Odette brought in its wake.

Stories from the storm

Amid his community’s instructions to evacuate, finishing his final requirements was Eugene Dela Cruz’s (1 AB EC-H) top-of-mind before the typhoon reached the shores of Hilongos, Leyte. While everyone was already packing up and moving, Dela Cruz was still in the middle of finalizing a presentation for one of his classes.

Dela Cruz only evacuated to a nearby hotel after checking most of his deadlines off his to-do list. Even then, he said that his main priority was to evacuate with his laptop because securing it was a matter of life and death for students enrolled in online classes like him.

When Dela Cruz arrived at the hotel, everything was swaying around him as if there was an ongoing earthquake. He saw cars flung around by the raging winds while trees and electric posts came tumbling down. Worried about his safety and anticipating that electricity would not be restored in time before his last deadline, Dela Cruz fled to Metro Manila a day after the landfall. He was right; electricity in some areas of his town has yet to be restored as of writing.

In Cebu City, Alicia Montesclaros (2 BS CH-MSE) endured the same nightmare. At first, no one from her family was alarmed over Typhoon Odette since Cebu City was no stranger to typhoons. It was only when Typhoon Odette was raised to a supertyphoon by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center that apprehensions started to shoot up.

The distress Montesclaros experienced during the night of the typhoon was evident. She expressed that aside from the damage on her room’s roof, seeing her ravaged community with no signal, water, and electricity was more upsetting.

Since the typhoon happened during the final leg of the semester, she worried that she had no chance of submitting her last academic requirements on time. Her professors extended the deadlines for her works, although signal problems in her area made it much more difficult for her to promptly comply.

Helping hands

For students like Dela Cruz and Montesclaros, receiving relief is crucial during and after the devastation of calamities such as Typhoon Odette.

Fortunately, the Loyola Schools (LS) administration worked hand-in-hand with the Sanggunian and other student organizations in times of natural crises to address the concerns of affected students.

For instance, the School Sanggunians immediately conduct constituency checks to survey the student body’s situation whenever there are impending typhoons. Once a student raises a relevant concern to the Sanggunian, they forward it to the appropriate LS office that can immediately provide assistance to the student. The Sanggunian also uses the data to lobby for policies that adjust academic deadlines until students recover from the calamities.

In particular, the Office of Admission and Aid (OAA) is one of the LS offices that keeps close contact with the Sanggunian during natural calamities. With the scholars as the priority, they conducted their own constituency checks to contact the students.

With both of them being scholars, Dela Cruz and Montesclaros felt grateful that the OAA representatives were first to contact them in the wake of Typhoon Odette. They added that the Office’s text message was worded in a genuine manner, which made them feel assured of the University’s care and concern.

Specialized needs

While Montesclaros and Dela Cruz appreciate the LS community’s initiatives to aid typhoon-stricken students like them, these efforts were not enough.

Both students emphasize how they struggled to submit their assessments by the deadline—even with the extensions in place—since they needed more time to recover from the typhoon’s aftermath. For instance, Dela Cruz scrambled to meet his deadlines because he had to find safety in Metro Manila all by himself. On the other hand, Montesclaros had difficulties connecting to the internet, which hindered her from keeping in contact with her classmates.

Montesclaros’ and Dela Cruz’s stories show that the road to recovery is never as simple as issuing a memo to push back deadlines by a few weeks or checking up on students via text.

If anything, their struggles after the disaster only point to the parallel storm that some typhoon-stricken students like them are still grappling with. This refers to the intense academic and psychological toll they must mount alongside the recovery efforts they must render to their own battered communities.

With this parallel storm, students like Montesclaros and Dela Cruz endured much more distressing post-storm experiences despite being affected by the same typhoon.

This goes to show that designing umbrella solutions may not be ideal in these kinds of situations. According to Development Studies Professor Mark Anthony Abenir, DSD, “Hindi pwedeng magkaroon ng one-size fits all na approach (There cannot be a one-size fits all approach.) The LS administration is responsible for communicating that [the approach].”

In order to effectively help their community, Abenir suggests that the LS administration work together with those who were directly affected to find what they need. This is in contrast to crafting policies that, as the students explained, did not completely help them.

Dela Cruz also suggests contacting the other sectors of the Ateneo community such as the students’ different organizations in order to expand the University’s reach. As seen by the turnout in the different donation drives, he explains that the Ateneo community is more than ready to help out their fellow classmates who were badly battered by Typhoon Odette.

Road to recovery

As remote learning continues to test students’ mental resilience and emotional stability, the need for the academic community to go the extra mile in compassion during unforeseen instances like typhoons becomes more apparent.

According to Abenir, the importance of the community in this trying time cannot be understated. “Well, napakaimportante building the sense of community among stakeholders especially students undergoing online education. May iba’t ibang aspeto na kailangan tingnan at maramdaman ng studyante,” he says.

(Well, it’s very important to build a sense of community among stakeholders, especially students undergoing online education. There are different aspects that need to be looked at and felt by the students. There will be a reinforcement of their needs.)

Aside from providing material relief, emotional safety such as by fostering a sense of belongingness is essential during these crises.

Moving forward, Abenir enumerates the best way the community can deal with any calamity they may face in the future: “Yung bukas na komunikasyon, pakikinig, pagrespeto kung saan man tayo nanggaling ay importante para tayo ay yumabong bilang isang academic community.”

(Open communication, listening, and respecting the different places that we come from is important for an academic community to thrive.)