In a competitive Asian society that prizes a Bachelor’s degree, three individuals remind us that futures still exist without a punctual graduation or diploma.

THE PHILIPPINE society has always valued traditional education—a linear path believed to lead young people to a land of career opportunities. Students set their eyes on graduation as a satisfying finish line, and parents are there to lay down the path for them, no matter the cost. However, this collective view casts a shadow on those who take unconventional paths to success, leading them to face speed bumps and hard turns in their educational journeys.

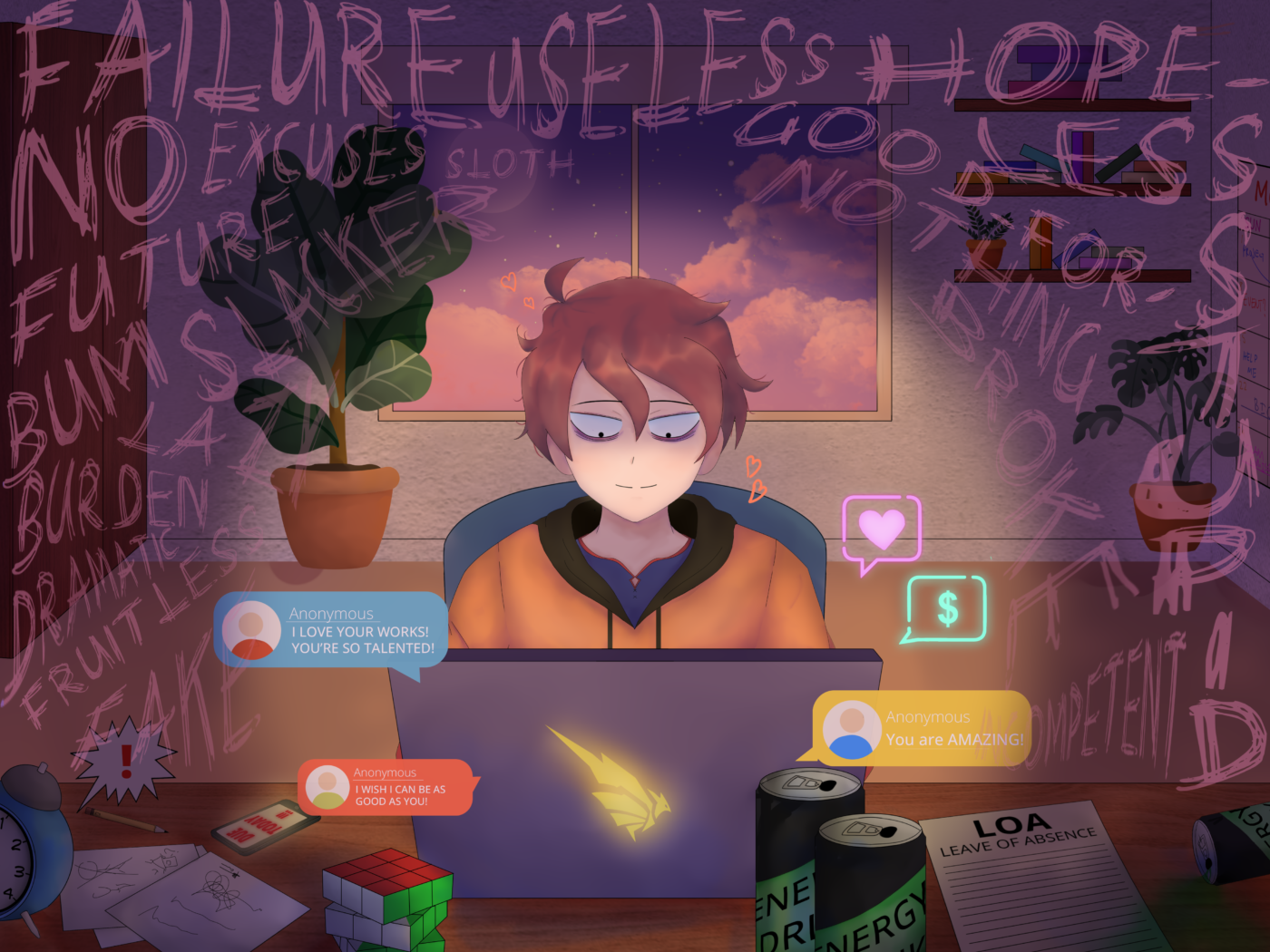

With the rising costs of higher education and a sudden shift to remote learning, more college students than ever have put a halt to their schooling. Though this decision is often accompanied by alternative pursuits toward learning, a deeply embedded stigma still persists.

Three former students share their stories of being out of school, showing that taking roads less travelled is by no means a lesser choice.

Out of the “race”

College is meant to be a pitstop, a place that polishes students before sending them into the real world, with a running start. University life provides people with specialized classes, leadership opportunities, and a space to create lifelong connections, serving as an ideal place for growth. Even with all of these things laid out, a few students share their stories of being unable to find their most fulfilled selves in college.

In January 2020, University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman student Caitlin Artates filed an indefinite leave of absence (LOA), but it took her strides to reach this decision. After an initial attempt to underload for a semester in UP Baguio, Artates would later transfer to UP Diliman in hopes of handling her bipolar disorder better. “While that improved my grades, it didn’t quite fix my motivation to study,” she shares.

When schools closed down a few months later, the pandemic worsened mental health and aggravated financial difficulties among Filipino students. Within a term of online schooling, both Rance Dizon (2 AB COM) and Leila* made a pivotal decision after unconducive experiences with the new setting.

“A lot of motivation went out the window as soon as second semester hit,” Dizon shares. He started neglecting his schoolwork, and his mental health suffered, prompting him to take an LOA at the start of his second year.

Leila, a former student from De La Salle – College of St. Benilde, admits to struggling with anxiety and screen fatigue from overwhelming workloads that were only aggravated by her Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). “I was functioning a lot better when there was still physical class,” she says. Leila stopped her schooling halfway through her second year.

Through plenty of self-evaluation and laying out reasons for leaving conventional education, these students mustered the courage to make the daunting choice. Even so, this is only the beginning of leaving the race, and the events that follow can pose even greater hurdles.

Back to the starting line

A society that is warped by meritocracy perpetuates social comparison and stigma. Young adults whose graduations are delayed or unable to be completed may face judgment from their peers, parents, educators, and future employers. Beyond these external perceptions is a far more important critic: The self.

Leila’s decision to drop out stemmed from the introspection of her capacities and future ambitions. With her parents’ full support, she invested her energy as a jewelry maker, allowing her to become financially independent and feel capable at her job.

Despite her positive experience with dropping out, Leila advises students to seriously contemplate leaving school given everyone’s varying circumstances. “Take a short leave instead, just for mental health, at least. It’s better to continue and graduate. I’m lucky to have loyal supporters, clients, and our family business to fall back on.”

Dizon consulted heavily with his loved ones, and while his friends immediately agreed with his decision, his parents initially discouraged him. “They were hesitant at first… they were thinking, ‘What will [you] do within that year of not studying?’” he shares. Eventually, he convinced them by expressing his grievances about online learning and promising to remain productive.

Initially, Dizon helped run their family business over the pandemic. Eventually, he took more time to nurture his passion for filmmaking as he applied for internships while working on projects of his own. Dizon highlights that he has unproductive periods too—and that is okay. “You shouldn’t always pressure yourself to do something. Focus on the little things that you’ve been neglecting,” he points out.

Dizon adds that he had consulted with the Loyola Schools Office of Guidance and Counseling (LSOGC) in processing the request as a general procedure for LOAs rooted in mental health concerns. During the LOA, the student’s assigned counselor will also check in on them through regular counseling sessions. This is all important so that students’ mental health concerns are addressed—hence why LSOGC Director Gary Faustino advises those who plan to file for a leave to visit the LSOGC immediately.

Faustino mentions an increase in students’ mental health concerns over the pandemic, associated with learning obstacles and a lack of “connection” online. “It has destabilized emotions. There’s an increase in anxiety [and] meaninglessness,” he shares.

Though he admits that it has been a complicated and difficult time, he affirms that the office and the counselors have “managed to adapt” in order to address students’ concerns with respect to their circumstances.

Education is not meant to be a race, but uncertainties abound when one strays off this common path. Regardless, the world is far from over—and a new chapter of self-discovery begins for those who’ve chosen the road less traveled.

Half a marathon

Leaving school and straying away from the traditional Bachelor’s degree path is far from easy. It has its rocky beginnings, and it comes with its detours—with some onlookers calling it a route for “failure.” Nevertheless, the experiences of Artates, Dizon, and Leila have proven that the road does straighten itself out.

In retrospect, Artates now feels that she has learned not only how to be independent but also more about herself. Today, she is both a graphic designer and a consultant for Mysterium, an institution for tarot and intuitive development. She has also since acquired a certification as a life coach and is looking forward to synthesizing it with her passion for tarot.

Overall, the three students’ time away from school allowed them to relearn what is most important: Self-growth, freedom, and one’s truth. The uncertainties of the future, after all, are always present. To this, Artates emphasizes, “You’re living your life for you. Find your truth and fight for it no matter what, and keep in mind that you’re worth fighting for.”

In these uncertain times, there is no one to judge, not even those who’ve taken the unconventional timeline. Their stories are a testament that regardless of the cards dealt—or in this case, the racecourse’s obstacles ahead—the finish line is always there.

*Editor’s Note: The name of the interviewee has been changed at their request in order to protect their identity and privacy.

—