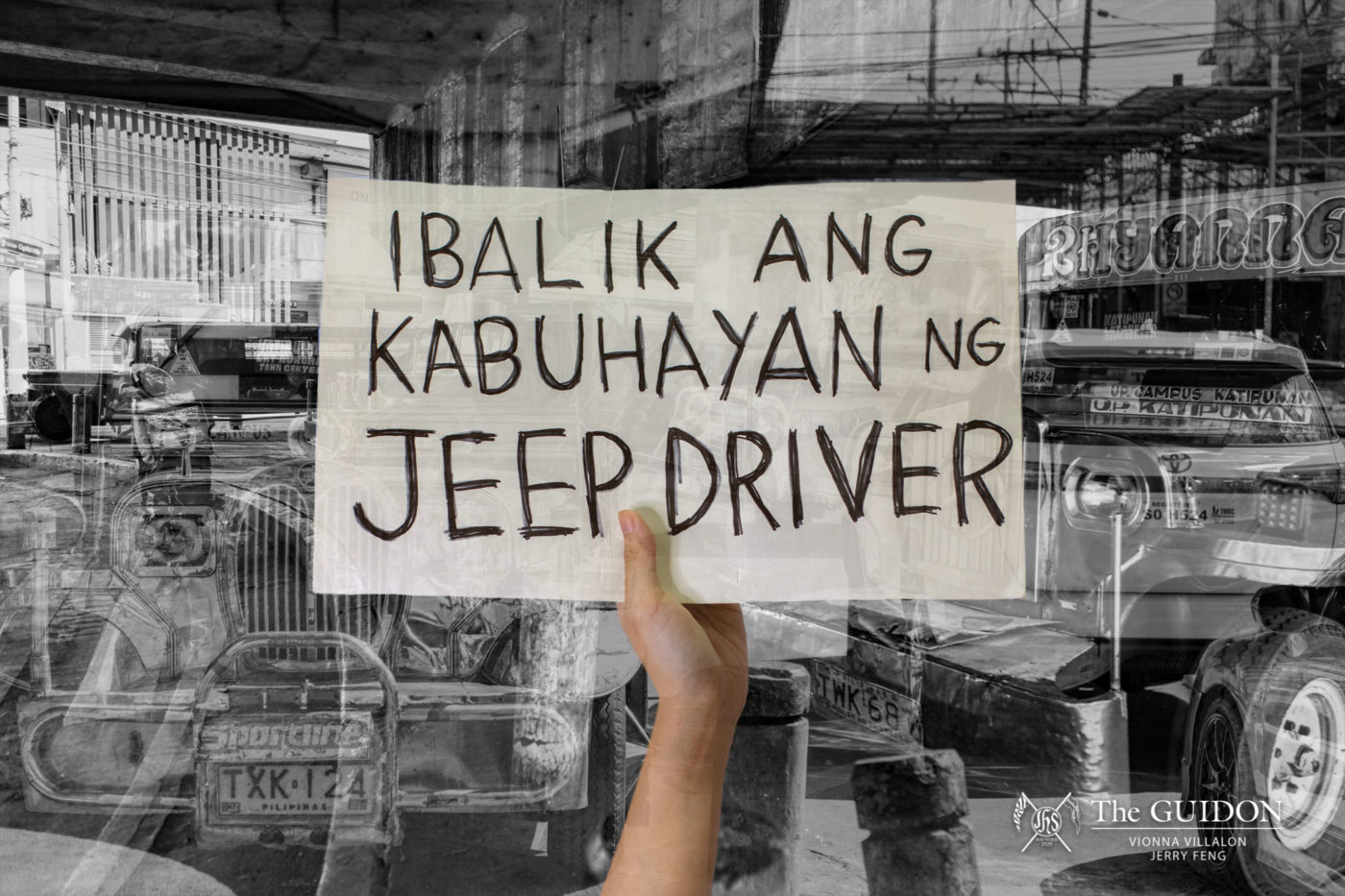

AS THE COVID-19 pandemic surged, scores of jeepney drivers were displaced from their jobs and forced to ask for alms on the streets. Today, the sector is not much better off despite the national government’s recent service contracting program. The program was meant to curb the competition for passengers and overcrowding rampant under the boundary system.

However, the policy was marred by questionable decisions made by the implementing agency, the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB). Its fraught implementation not only spells economic distress for jeepney drivers but points to leadership that routinely understates the importance of equitable mobility.

Hitting red lights

Access to the service contracting program has been severely constrained. Move As One Coalition Sectoral Convener Hyacenth Bendaña noted that the LTFRB aimed to enroll only 60,000 of the more than 160,000 jeepney drivers nationwide. As of June 2021, only 11,346 are active under the program.

The rest who hope to get in must wade through red tape. Bendaña stressed that many drivers are not in a position to comply with the LTFRB’s many requirements. For instance, Bendaña’s father shares a franchise with nine other drivers, as they had to split the cost of Php 400,000—even if a franchise is supposed to be free. However, only one of the 10 can use the franchise to be eligible for contracting.

With only a minority in service contracting, most drivers had to continue under the boundary system. This dynamic led to friction among transport workers. “Kasi siyempre, bakit [pa] kumukuha ng passengers ‘yung nasa service contracting, eh regardless naman kung may pasahero or wala, may kita pa rin sila? (Why are those under service contracting still taking passengers when they are already guaranteed pay?)” Bendaña explained.

The LTFRB’s Libreng Sakay (free ride) program further disadvantaged drivers under the boundary system because they had to compete with a service offered for free, she added.

Even with the new system in place, jeepney drivers under service contracting also felt the adverse impacts of a mismanaged program. Bendaña noted that drivers had to adjust from earning daily through passenger fares in the boundary system to getting paid weekly for every kilometer traveled. However, many went without pay from December 2020 to April 2021, only to receive incomplete sums as low as Php 12 for four months’ work. Though transport cooperatives momentarily shouldered some drivers’ income, Bendaña noted that many are yet to be paid their dues.

Misunderstood mobility

The gaps in service contracting are indicative of an agency resistant to the voices of the transport sector. Bendaña said that the Move As One Coalition and transport worker community, who have long been fighting for the program, were excluded from the implementation process. The result was a policy whose benefits were drastically limited.

Initially, advocates designed a policy meant to curb the COVID-19 spike in three hotspots: Metro Manila, Metro Cebu, and Davao. However, the Php 5.58 billion budget under the Bayanihan to Recover As One act was applied to the whole nation.

The LTFRB also failed to engage local government units and opted to implement the program on their own, Bendaña said. She noted that the LTFRB hastened the program’s rollout after being flagged by the Commission on Audit (COA) for slow disbursement. However, the rollout system remains to be disorganized with more than half of the Php 5.58 billion fund still undisbursed as of September. Relaunched in the same month, the program also has a Php 3-billion budget under the 2021 General Appropriations Act (GAA) set to expire in December.

In response to the slow payout, LTFRB Chair Martin Delgra asserted that there was no lapse in the program’s management, saying that the delay was a matter of banking processes. He also clarified that the agency has released not Php 59 million—per COA’s report—but Php 1.5 billion or 26.6% of the fund. The rest was returned to the Treasury. It remains to be seen if the LTFRB can promptly disburse the Php 3 billion fund under the GAA. With service contracting’s relaunch, Delgra has emphasized that expediting payouts relies on drivers having a Landbank account.

As Bendaña explained, service contracting was meant to be the first step in a “just transition” to jeepney modernization. With little support for modernization to begin with, Bendaña lamented that the lapses in service contracting fueled drivers’ distrust in the government. Some doubt service contracting altogether. Nonetheless, Bendaña remains hopeful as many in the sector see no better alternative.Ultimately, service contracting is only one part of the larger causes of mobility and spatial justice. There is a need for Filipinos—those in power and on the ground—to reckon with the hefty costs of a car-centric culture that harms everyone. “Space is a finite resource. We can’t build expressways and roads forever; we can’t just have cars forever,” Bendaña asserted. “Otherwise, by 2030, we will not have the cities we want.”