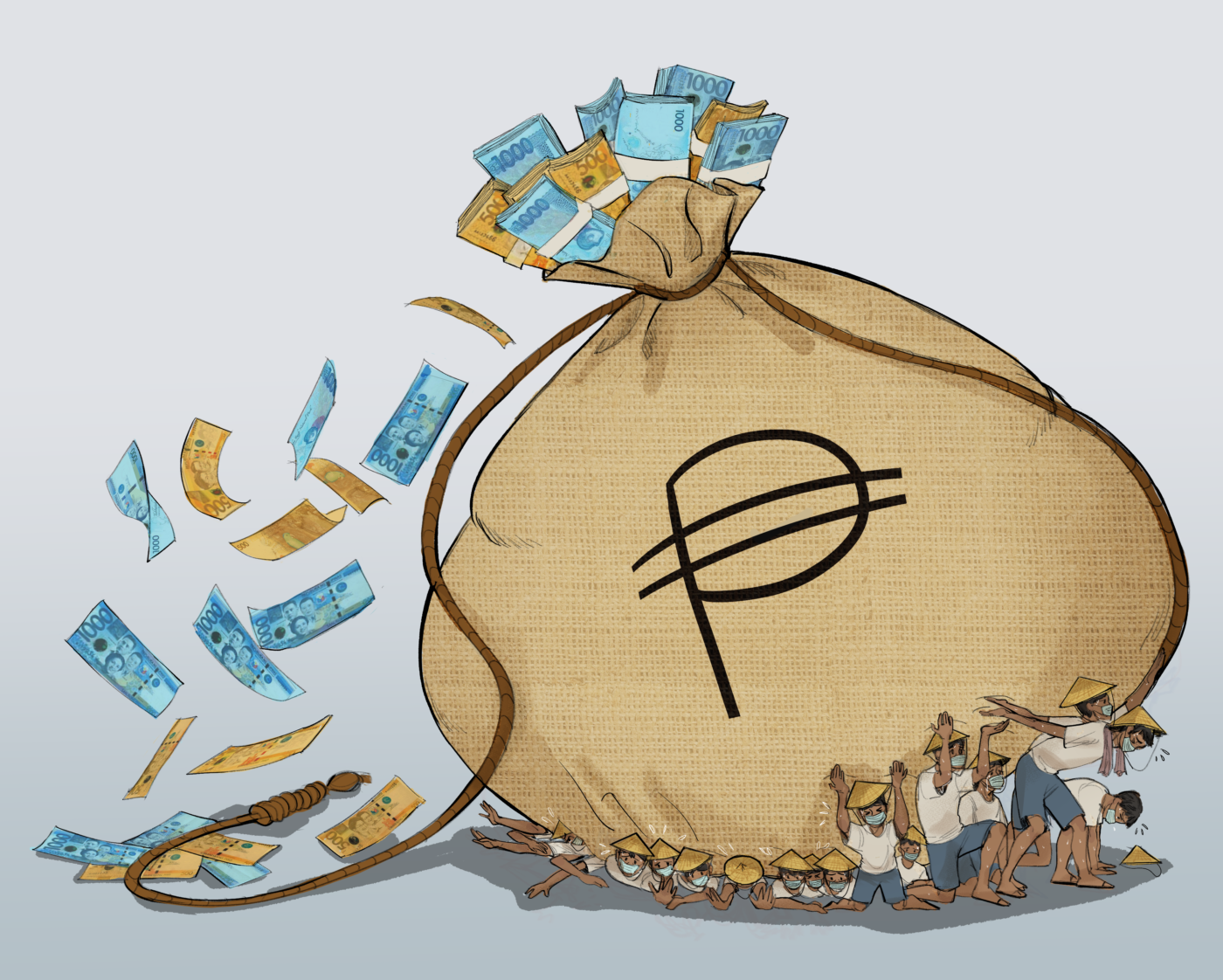

WHILE THE discovery of a COVID-19 vaccine may have ushered a more promising end to the pandemic, questions regarding the Philippines’ road to economic recovery abound. Totalling Php 9.79 trillion at 2020’s tail end, the large increase in government debt due to the economic recession has raised concerns regarding its sheer size. With this, the government’s use and management of debt will be consequential in relieving Filipinos of the pandemic’s economic blows.

In contrast to public confusion on debt, several experts have repeatedly argued in favor of the government increasing borrowings to fund economic efforts that relieve lower socio-economic strata. Before the 2021 budget was crafted, economists noted that there is fiscal leeway to maximize loans in order to further encourage consumer spending.

Fears from the past

Although the last decade witnessed a relatively stable and progressive economy, public unease surrounding debt persists. This anxiety is rooted in the country’s turbulent and painful past, when government borrowing sprees in the mid 1970s to early 1980s signaled a troubling time for the nation.

At the height of his power, the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos increased public debt from 30 million USD in 1962 to 28.3 billion USD in 1986. While the money funded many government projects such as the San Juanico Bridge, the country barely reaped the economic rewards as debt thrice exceeded the average gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate. As international reserves dwindled, import-reliant industries shut down—forcing Filipinos to suffer from the high cost of goods.

Meanwhile, Marcos granted loyal cronies command of key industries to create a monopolized private sector. Rampant corruption in public infrastructure projects such as the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant further hindered economic development.

The mismanagement of debt, along with the influence of external factors such as rising global interest rates, plunged the country into the 1983 Debt Crisis, where Marcos requested a moratorium on foreign principal payments. The three-month postponement extended for more than a year, straining the country’s relationship with international creditors. During this period, the economy took a downturn as the manufacturing sector went into distress, investment plummeted, and underemployment rose.

To this day, the Philippines is still reeling from the Marcos administration’s financial missteps—along with citizens shouldering the burden of interest payments from its loans until 2025.

Prime interests

35 years after Marcos’ martial law, President Rodrigo Duterte claims the country is sinking “deeper and deeper” in debt. With mass vaccination estimated to begin in the third quarter of 2021, the Philippines finds itself in a deadlock—seemingly between public health and the economy.

With this, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted both monetary and fiscal problems within the country. According to Ateneo Center for Economic Research and Development Director Alvin Ang, PhD, pandemic conditions have disrupted regular relations between producers and consumers, inflicting heavy tolls on income and mobility.

32% or Php 2.864 trillion out of the Php 9.8 trillion worth of debt amassed since the pandemic’s onset originate from international non-governmental organizations. For a country with a history of foreign debts, the sizable amount of this figure may appear alarming.

However, these foreign loans were mostly sourced from the ADB and the World Bank—both international organizations that do not lend money to countries without a sufficient investment grade. “They have rated us as investment grade, meaning we are a country that can borrow…and can repay all our debts,” Ang stated.

Ang added that the Php 9.8 trillion figure was still less than 20% of the country’s GDP. The bulk of the dues consisted of domestic debt, which is amassed when the government borrows from citizens through bank treasury bills. Ang noted that because of this, the state would encourage higher spending in order to collect taxes and repay the accumulated domestic debt.

Balancing foreign and domestic debt are both highlighted as strategies for financial management—especially amid emergency situations. In a public health crisis that has caused rapid economic decline, and even overwhelmed and spread the working sector thin, financial limitations have become sidelined. “These limitations, generally you have to set them aside to pump-prime the economy,” Ang stated.

Amid shocking figures aggravating the country’s economic burdens, Ang clarified that the country customarily repays its debts and would therefore not borrow without the capacity to repay its creditors. This is reflected in the Philippines’ investment grade and creditor nation status under the International Monetary Fund.

Presidential Decree No. 1177 or the Automatic Appropriations Law also automatically ensures that a portion of the national budget is allocated for debt servicing. This highlights financial safeguards and stable economic patterns that may provide a source of relief to the concerned Filipino citizen.

A balancing act

As far as any visible effects incurred debt may have on Filipinos, Ang stressed that Filipinos will not be severely affected by the eventual process of paying off loans. What concerns Ang is how Filipinos, producers and consumers alike, will respond to the government’s efforts to stimulate the economy. If such efforts are unsuccessful, Ang noted the government may need to borrow more—however, this might not be a viable option. “…the government [has already] set targets—[they] only borrow [up until this] point. They have to raise the rest through other means,” Ang says.

A holistic understanding of debt in the economy, then, is necessary. As Ang suggested, debt cannot be seen in isolation; it must be considered relative to the nation’s capacity to pay its dues. “The capacity is there—it’s you and me and everyone else. We are the capacity of the economy to pay. If we are not doing anything, then the economy will have a problem.”

Given the slow pace of the economy’s recovery, Ang stressed that it will be imperative for the government to maximize its options in stimulating economic activity. While consumer confidence is currently on the upswing, Ang remarked that it is not rising at an ideal rate. To supplement the government’s efforts, he regarded that a good public communication campaign is necessary in the current context in order to further build economic trust.

Ultimately, the economy’s recovery cannot be seen as separate from issues concerning public health. As Ang emphasized, producer and consumer confidence will not be restored if the virus still lurks, stoking fear and preventing Filipinos from participating freely in economic activities. If the pandemic is not contained, then efforts to relieve economic misery will be for naught.Apart from strengthening its vaccination program, the government also bears the responsibility of letting Filipinos know where their money is going. While incurring debt is necessary, it remains to be seen whether the borrowed funds are spent correctly, and this is where Filipinos must demand transparency from their leaders.