AS THE Philippines began securing vaccine deals, Foreign Affairs Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr. accused Health Secretary Francisco Duque III of “dropping the ball” on a vaccine deal with Pfizer. The friction between these two Cabinet secretaries may point to potentially faulty collaboration between their agencies.

In light of recent developments, President Rodrigo Duterte has only reaffirmed his trust in Duque despite the latter admitting to the persistence of corruption in the Department of Health (DOH). Duque has responded to calls for his resignation, asserting that “[Cabinet members] all serve at the pleasure of the president.” These events have underscored the need to clarify the president’s relationship with his Cabinet secretaries and how the latter ought to uphold their mandate.

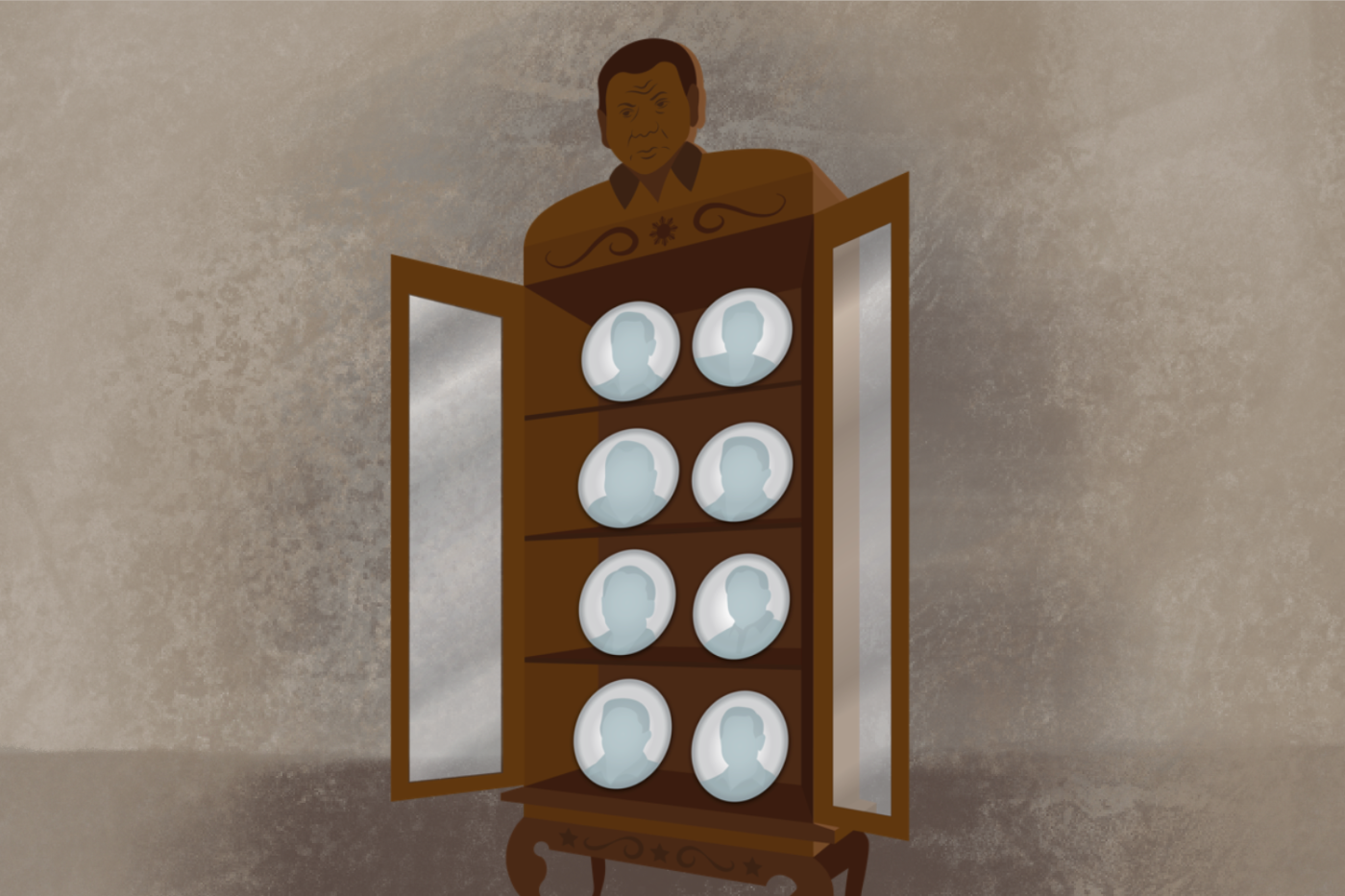

All the president’s men

Political Science instructor Gino Trinidad described the Cabinet as “the president’s alter ego.” They are composed of executive departments’ heads, each at the forefront of carrying out executive functions and facilitating policy implementation. Government agencies are inevitably interdependent as matters of national concern often require collaboration between offices.

While vaccine procurement is a multifaceted issue, the sectoral nature of agencies is key in deciding which body should take the lead. “For example, the mission is to procure vaccines. The DOH should head that because they [supposedly have the competence]…of checking what should be the best vaccine,” Trinidad said. “But the DOH is not really mandated to, for example, strike deals with other governments or entities.”

Trinidad further explained that the president’s legitimacy partly relies on the success of Cabinet secretaries, as the latter are appointed solely on the basis of executive prerogative. Though this is the case, Trinidad pointed out that Cabinet members are still bound to their office’s mandate. “Given that they are appointees of the executive, it does not automatically mean that they cannot exercise their autonomy from the president,” he emphasized.

Ensuring that executive appointees can fulfill and stay true to their mandate falls within the functions of the Commission on Appointments (CA), which provides the corresponding check to the presidential appointing power. Headed by the senate president, the CA is composed of 12 senators and 12 house members selected based on proportional representation of parties represented in Congress. The CA reviews executive appointments, accepting or rejecting them based on the commission’s terms. “The main criteria [are] fitness and merit—whatever [those] mean,” Trinidad said, highlighting the subjectivity that may accompany such decisions.

At the president’s pleasure

Despite the checks and balances between the CA and the president, the latter’s power still holds at the end of the day. “In Philippine politics, persons are important. And the unifying person, of course, is the president,” Trinidad stressed. In a regime like Duterte’s where he enjoys the support of the supermajority in the legislature, existing checks and balances may prove limited.

In the Philippines, a weak party-list system is a contributing factor to the president’s strong sway, according to Trinidad. Instead of their parties, politicians work in terms of personalities. This weakens party identity and party-building, which makes shifting parties—and ultimately ideologies—easier for government officials.

Because of Duterte’s supermajority, it is expected that most of the members of the CA and the Cabinet will share certain ideals and values with him. This ideological alignment may aid in the efficiency of the decision-making process, but the lack of opposition could breed a hostile environment for anyone with dissenting opinions.

The president then becomes even more influential since the weak party-list system, coupled with the supermajority he enjoys, affords him more control over policies, programs, or laws. “[The supermajority] might facilitate a lot of things, but efficiency here does not always mean that it is the right decision,” Trinidad argued.

Regardless, Trinidad pointed out that the Cabinet and the CA should be separate and impartial for checks and balances to work. However, the president’s solid authority over the legislature has proven that certain things may be overlooked, such as the militaristic response to crises such as the pandemic.

Furthermore, the primacy of the president’s wishes has also prevented officials, such as Duque, from being held accountable. “It does not also help much that the President uncritically somehow accepts the performance of the Health secretary, at least in this very specific context,” Trinidad said.

The character of the Cabinet and the CA both reflect a kind of governance that is increasingly undemocratic as there is less and less space for the opposition. While dissent is critical to the current context, the avenues for pushing back seemingly continue to grow sparse.