AS CLASSES across the country commence, students and teachers alike face the logistical and personal difficulties of distance learning. Meanwhile, others remain unenrolled due to financial and resource constraints amid the pandemic. Despite this, the Department of Education (DepEd) and Commission on Higher Education (CHEd) pushed through with the academic year 2020-2021 and rejected calls for an academic freeze, stating that they have been preparing to ensure that education is delivered through various modalities.

Although the Alternative Learning System grants out-of-school youths the opportunity to pursue learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic, students’ collective struggle to adjust to online learning reveals that access to education remains well beyond arm’s reach.

Class struggles

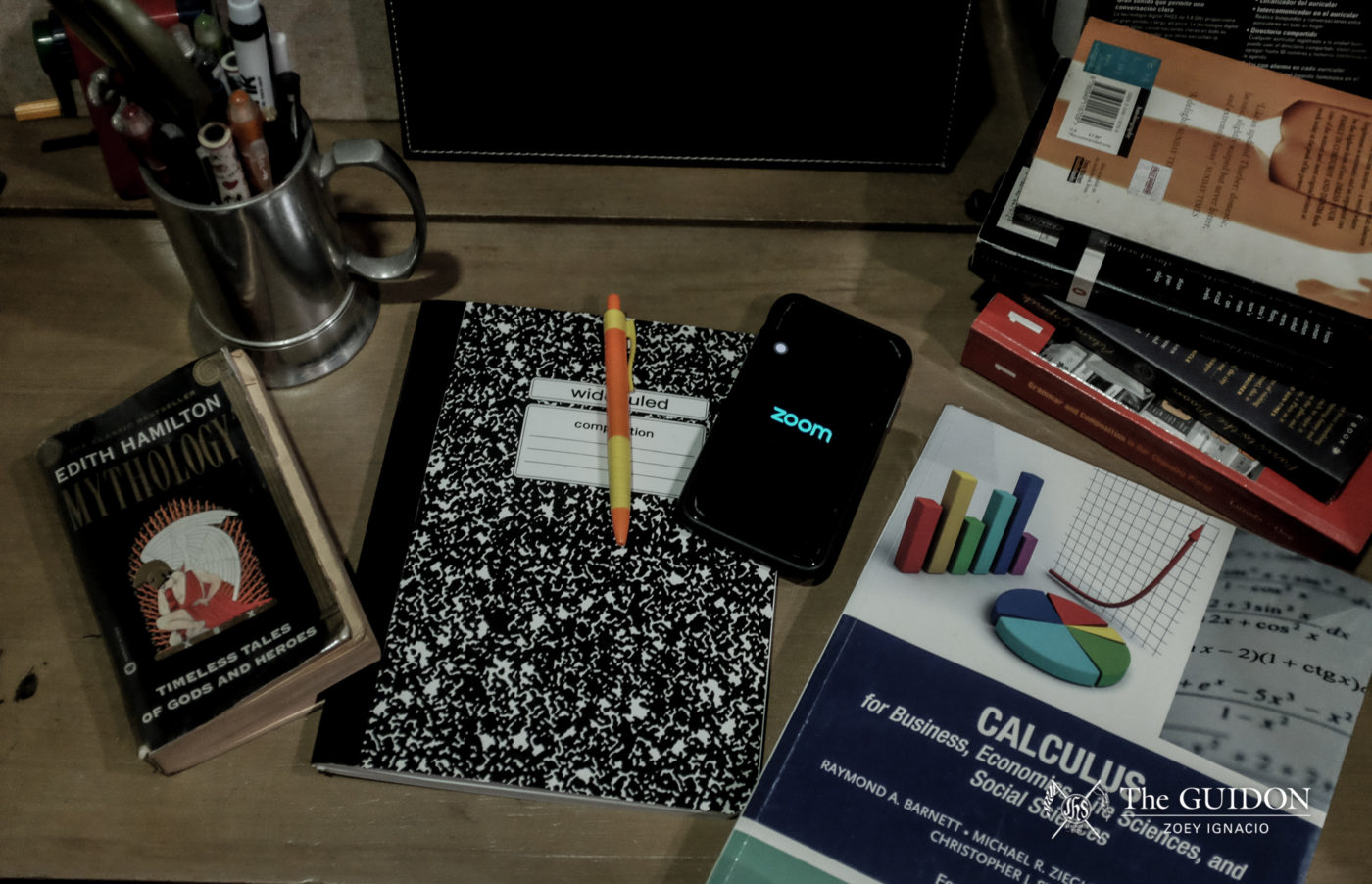

The first few weeks of the academic year bore witness to students wading through the various struggles that beset online education. Unstable internet, lacking gadgets, and difficult self-paced learning confronted students who fear being left behind.

For instance, University of San Agustin Iloilo medical laboratory science major Wesley Dauban has been taking online classes through mobile. For Dauban, this drastically affects his ability to focus on his education.

“[Limited] lang din ang features ng phone unlike [a] laptop or any other device na suitable talaga for online class (A phone only has limited features unlike a laptop or any other device that is suitable for online class),” Dauban said.

Dauban also pointed to his unstable connection, noting that he relies on prepaid mobile data since his hometown in Palawan lacks access to internet service providers.

Another case to consider is Cavite State University – Carmona marketing major Rica Turay, who resorted to online selling to meet their family’s basic needs after her father lost his job. Like Dauban, Turay also relies on—and must earn income for—mobile data for online classes.

“Kami nalang dalawa ng ate ko yung nagpupursige mag-online selling para may pang araw-araw (It is just me and my sister persevering with online selling to earn for our everyday needs),” she added. Turay also noted that she has to share mobile data and one donated laptop with three other siblings.

In addition, Turay and Dauban mentioned how learning has been difficult for students grasping lessons on their own, especially since it is challenging to interact with professors due to limited synchronous classes, internet connection, and gadgets. Additionally, they also stressed that unconducive studying environments in their homes, occasional disturbances from relatives, and coinciding daily house chores affect their studies.

Amid such issues with online learning, DepEd and CHEd continue to reiterate that they are pushing for “flexible” and “blended” modes of learning that utilize self-paced modules to limit students’ online screen time. However, shortages in module materials and constant technical issues in the online setup continue to challenge these assurances—painting uncertainty for the school year ahead.

Left behind

While many students struggle with online learning, others such as Jeremy Tangpuz have been forced to sit out the academic year. A mechanical engineering student at Adamson University (AdU), Tangpuz anticipated that the psychological tolls and financial cost of online learning would compound his existing burdens. Instead, he chose to focus on making a living and helping his mother run their small eatery.

For students like Tangpuz, formal education may be put on hold indefinitely, as the reopening of schools largely hinges on the discovery of a vaccine. Tangpuz is proof against CHEd’s claim that flexible learning “ensures the continuity of inclusive and accessible education.” He noted that AdU did not even offer him options beyond online learning.

CHEd’s passive role in preventing the loss of years’ worth of learning has only aggravated these issues. Aside from deferring decision-making to higher learning institutions altogether, CHEd sidestepped criticisms by disregarding the varying capabilities and resources of universities. “We are ready because our top universities have been doing flexible learning even before COVID,” CHEd Chairman Prospero De Vera III asserted.

As the school year marches on with little consideration for Tangpuz and millions of other unenrolled students, the Filipino youth potentially face losses—both academic and economic. In the meantime, students like Tangpuz are left to weather the consequences of a year without formal schooling—with a recession looming large, no less.

Held hostage

Like students, educators had limited choices heading into the academic year. Initially, Jo-Ann Rae Macarandan—a Junior High School mathematics teacher at San Beda University Rizal—perceived an academic freeze as imperative to the current context. She questioned her future in teaching as the premature birth of her son last April meant that she could barely prepare for online classes.

“Numerous times, I told my husband na, ‘Ayaw ko na, ayaw ko na ata magturo (I don’t want to teach anymore),’ because I don’t know what to do and I’m not prepared,” Macarandan said. Still, she needed to earn a living, especially since her son’s hospital bill was costly.

Despite teaching six classes and over 200 students and often without knowing when she can finally rest, Macarandan does not lose sight of her privilege. “[…] Administrators, they are just keen [on] telling us na we are very blessed that we still have work, so we go about the things that we need to do.”For both students and educators alike, learning has been reduced to an act of survival—a burdened effort to prevent being left behind amid these turbulent times. As both DepEd’s and CHEd’s efforts remain severely lacking, the public is again left no other recourse than to keep pressuring its leaders to make learning more accessible. However, if the past is any indication, then public servants may have scarce compassion to spare for this vulnerable sector.