AN ARRAY of pink products will greet you in the toiletries aisle—pink toothbrushes, razors, cotton buds, tissue packs, and lotions. These smaller items always seem to strike a contrast with the exact same products of a more “masculine” branding nearby. Moving to the checkout counter with your pink toiletries, a pink Kinder Joy chocolate with a proud “for girls” label sits on a shelf near the cashier. Beside it is a blue one labelled “for boys.” Somewhere, a little boy hesitates to reach for the pink version, conditioned to think that labels are meant to restrict his choices.

Advertised with labels that promise the products will better suit your female body, these smaller pink products actually cost more than their “masculine” counterparts. These slight price surges demonstrate the practice known as the pink tax, a traditional gender-based pricing that makes products intended for women cost more. Pink tax is not a formal taxation, but its roots lie in marketing and the cultural constructions of womanhood.

Packaged femininity

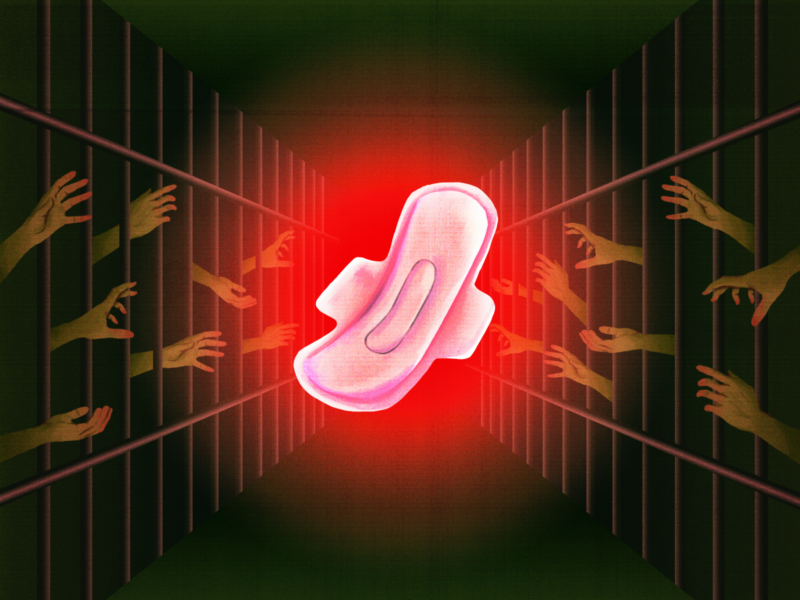

Pink tax ensures that being a female in this society will entail a lot of costs. In an experiment conducted by Mic Senior Correspondent Elizabeth Plank, it was estimated that in her lifetime, a woman in the United States spends USD 100,000 on products affected by pink tax. The most inevitable additional cost women have to pay per month are sanitary napkins. A woman spends USD 4,752 or Php 237,600 on sanitary napkins alone in a span of 33 years, the average timeframe in which a woman remains fertile.

Reproductive Health and Gender Advocates Movement Chair Joie Cortina shares that although pink tax is not a formal taxation system, it is a pervasive cultural practice towards product pricing that shapes the economy. “Femininity becomes a project that requires all these resources,” Cortina notes.

Cortina emphasizes the apparent disparity by comparing the hypothetical situation of two fresh graduates, saying that to land a job, a woman will have to invest more on her grooming than her male counterpart. “That same amount that would go to pink tax, her male counterpart can put into savings,” she says.

She adds that some products’ features promise attainment of an impossible standard of female beauty. “This problematic logic is apparent in this thinking: ‘So what if a razor that happens to be pink is significantly more expensive than the blue one?’ We are happy to get the pink one because it has this moisturizing aloe strip. Same goes with the pink deodorant that promises whiter underarms and freedom from chicken skin. A proper woman can’t have dry skin or dark pits,” Cortina notes.

The daunting reality is that purchasing products that enforce unattainable standards of femininity is advertised as supporting female empowerment. “While oppressive, some women consider this a locus of power. ‘I can buy this. I am, therefore, powerful,’” Cortina says. Yet, even more daunting, this notion of empowerment strengthens the burden that weighs down many financially challenged women in society. How can the consumption of products intended for women be for female empowerment when millions of other women are financially incapable of doing so?

Bigger puddles of pink

Although the effects of this phenomenon are felt by women, pink tax can be a worse enemy to consumers of all kinds when analyzed from a marketing perspective.

The market continues to tailor their prices to consumer behaviors for the sake of profit. For example, Fourth Wall Global managing partner Dae Lee says that if people are willing to pay more for a product they believe is more prestigious, markets raise the value of that product. Consumers prefer a more expensive product because they think it is of higher quality, fits their aesthetic, holds a symbolic meaning, or aligns with trends—like white being a consistently popular car color because of Apple’s iPhone colors.

“They put the cost into the consumers,” Lee says, adding that the marketing world is a place that is prone to unfair treatment of its consumers. He says that the way consumers behave allows marketers to continue this profiting mechanism because “behavior-wise, the funny thing is, [both] men and women buy the premium perceived value[s].”

Lee advises consumers to step back and consider: “When you think about it, is there really [a] pink tax? Yes, maybe, but in the bigger picture…markets need to be really honest with the products [and] not use behavior to change pricing.”

While consumers are being read like open books, markets adjust accordingly and strategically in order to profit. Without realizing this, people’s values and relationships affect their spending behaviors. To this, Cortina reminds that “the performance of economic gender scripts, as all other domains of our gendered existence, recapitulate oppressions.”

Before checking out

Although removing pink tax would be ideal, the responsibility of reducing the effects of pink tax does not only depend on the honesty of markets. Markets, in the end, still respond to consumer behaviors.

Of course, individuals can still change their purchasing habits to avoid the effects of pink tax. For products that are similar in quality, women could opt to buy the “male” or gender-neutral item instead. Another solution is to choose companies with fairer pricing and boycott those that do exhibit pink tax.

While consumer behavior is integral, the rationale behind product pricing is also rooted in culture. To remedy this, policy changes can lead to better cultural understandings of gender and purchasing values. “Through education, we can shift values and create an environment where individuals are more empowered agents as they perform their gender—even in the economic realm,” Cortina adds. Attempts to ease the tension of gendered-economics are being implemented through policies such as the Department of Education administrative order for comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) for K-12 students.

According to Cortina, the CSE underscores the importance of “shifting away from capitalist-patriarchal ‘values,’ to truly gender-transformative ways of thinking, relating, and doing.” Cortina believes that this can be accomplished by integrating CSE elements in the basic education curriculum. With educational changes operating in the background, age-appropriate learning programs and materials on adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights may give students a better grasp of gender equality in day to day events.

However, policy changes can only do so much. At the end of the day, lasting change rests on the consumer who can consider an important question from Cortina: “[Is this purchase] truly acting on empowered economic agency or [does it] just [ strengthen a] system that features a marriage of capitalist and patriarchal values?”

The pink tax is more than just a marketing tactic that affects numbers on price tags. It is an example of how the market continues to take advantage of consumer behaviors—which are affected by the societal expectations on women to fit an ideal. However, consumers must remove the rose-colored lenses and see the pink flags more clearly.