IN THE hush before dawn, life in the city seems perfect. Roads are free from the whirring sounds of a thousand engines. Drawn curtains in two-story homes stave off the day’s work a little longer. Hardly anyone is awake to worry about what tomorrow holds.

Miles away in the countryside, coconut farmers out in the fields find no such illusions in the twilight. The past four decades did not gain them much ground in their drawn-out battle against plunder, and still, new challenges are mounting.

Currently, a horde of problems hounds the coconut industry. Steep drops in prices of coconuts, a lack of infrastructure support, and increasing vulnerabilities to crop destruction by calamity or infestation are only some of the pressing issues confronting coconut farmers.

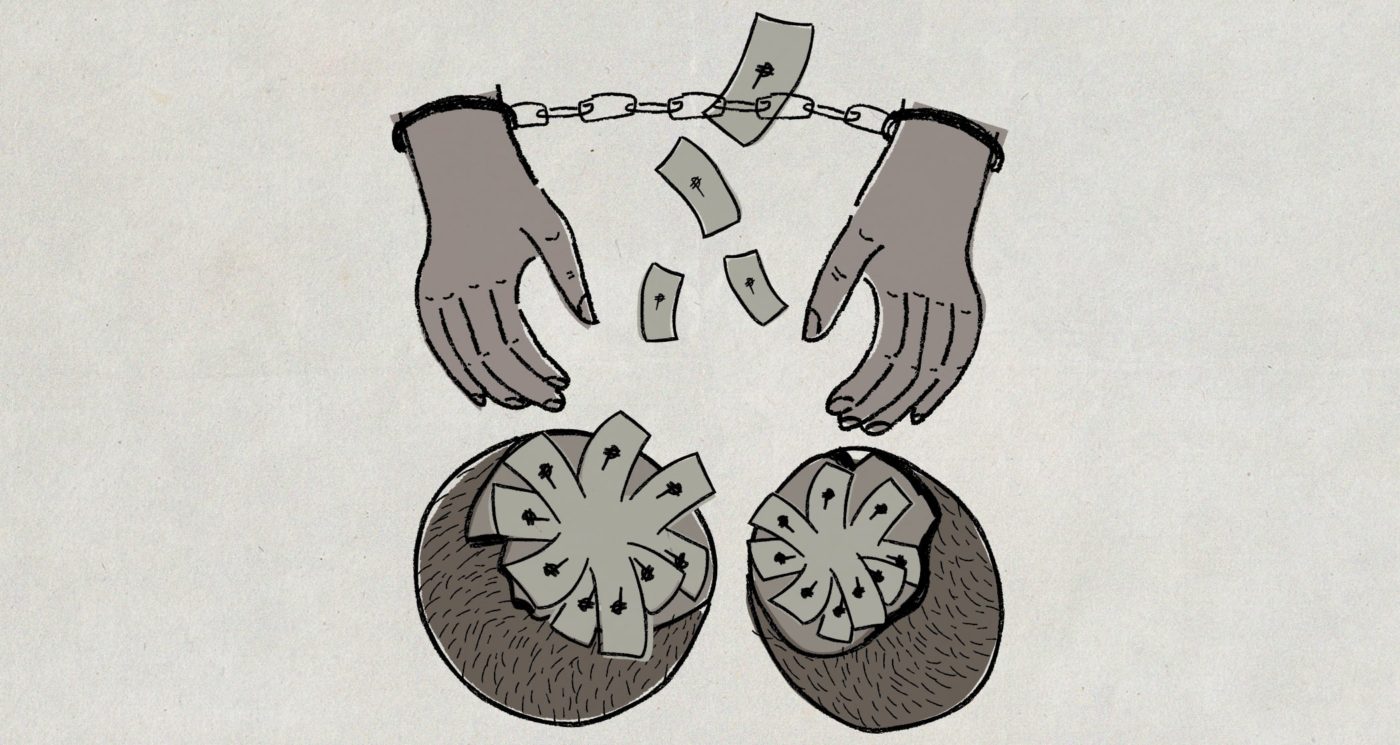

Corruption is another. Dating back to the dictatorship of former President Ferdinand Marcos, the coconut levy scandal has not seen any successful measures taken towards its resolution, with billions of pesos generated from the program still locked in national treasury. In 2018, farmers believed their claims to the funds would finally be granted following the passage of the Coconut Farmers and Industry Development bill in Congress. However, the measure was ultimately vetoed by President Rodrigo Duterte last February over a lack of legislative “safeguards,” pushing farmers back to square one.

Where it all began

The controversy around the coconut levy fund unfolded upon the enactment of the Coconut Investment Act or Republic Act 6260 (RA 6260) in 1971. Effective from 1972 until 1982, the law imposed a tax on coconut farmers equivalent to Php 0.55 per 100 kilograms of copra, Php 0.50 of which was to be funneled into the Coconut Investment Fund. The outstanding balance of Php 0.05 was allocated to the Philippine Coconut Administration and the Philippine Coconut Producers Federation (COCOFED).

In addition to these provisions, RA 6260 also established a Coconut Investment Company (CIC) to capitalize and administer the collected funds. RA 6260 conferred to the CIC the objectives to “accelerate the growth of the coconut industry” and to ensure “stable and better incomes” for coconut planters.

Throughout his administration, Marcos ordered the creation of several other funds that levied taxes on coconut farmers, issuing decrees thereafter every so often to amend their structure and functions. Among these ensuing funds, the Coconut Industry Investment Fund (CIIF) was most significant.

Instituted through Presidential Decree 961, the CIIF was siphoned by businessman Eduardo Cojuangco Jr. and his associates into 14 holding companies whose assets included 47% of San Miguel Corporation (SMC). At the time, Cojuangco notably served as the president and chief executive officer of the United Coconut Planters Bank (UCPB), the administrator of the CIIF.

From 1971 to 1983, around Php 9.8 billion was collected from farmers as part of the coconut levy program. Excluding those pending litigation, assets relating to or acquired through the coconut levy were estimated by the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG) to be worth Php 93 billion.

In 2018, two proposed bills were ratified by Congress that many hoped would finally return that sum to the coconut farmers. The first bill, also known as House Bill 5745, aims to create a Coconut Farmers and Industry Trust Fund (CITF) “which shall be for the ultimate benefit of coconut farmers and the coconut industry.” The second bill, House Bill 8552, would strengthen the Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA).

These twin bills would allow a reformed PCA to manage the trust fund and would field six coconut farmers and one coconut industry representative as members of the PCA board aside from government agencies. The bill would also use Php 5 billion every year from the coco levy fund for various farmer benefits such as scholarships, shared facilities, health benefits, farmer organizations, and farm improvements.

Initially, the Malacañang was concerned over the idea of farmers making up most of the PCA board members, calling for a dominant government presence rather than civilians running the fund. However, even after Congress adjusted the bill in favor of a bigger government makeup in the PCA, the President still rejected the bill, reasoning that the measure lacked “vital safeguards.”

No end in sight

With both bills vetoed and copra prices still on the low, coconut farmers see no end in sight to their hardship. All over the country, farmers are struggling to make ends meet. From 2017’s farmgate price of Php 38.70 per kilogram of copra and last year’s Php 22.38 per kilogram, the average price per kilogram of copra between January this year until June is roughly at Php 14.50.

“It’s as if [copra] has no value anymore. Theft on coconut has disappeared because even thieves don’t think they’re worth it anymore,” Kilusan para sa Repormang Agraryo at Katarungang Panlipunan or Katarungan Secretary-General Dan Carranza said.

With copra being the primary and usually only product that coconut farmers know how to produce, they are finding it hard to breakeven due to the lack of alternative products.

“Coconut farmers don’t know what else to produce other than copra and walnut,” Carranza said. “Coco sugar, virgin oil, coco jam, vinegar, cookies–there are so many products you can make [from coconut].”

Carranza mentioned that the distribution of the coco levy fund could open up those alternatives and opportunities for farmers like himself. This would not only save them during the present time of crisis, but also improve the industry in the long run.

“It may take five or six years for farmers to be able to market different products to different communities,” he said. “But first, you need to use the coconut levy funds to provide [farmers] access to technology and capital for making vinegar, coco sugar, and other products that the local market can use.”

“That way, the market is developed and they’ll have more income,” he added. However, instead of providing that support, Carranza said the present administration might be vying to use the funds for the Build, Build, Build program, its flagship infrastructure initiative.

“The government doesn’t see [coconut farmers] as the real owners [of the fund],” he asserted. “I think [the distribution of the fund] has been delayed because what Duterte is after is the usage of the fund in the way that he wants, not in the way that coconut farmers want.”

In his 2019 State of the Nation Address, President Duterte once again called for the passage of the coco levy bill, but many farmers and sectoral groups like Katarungan may be skeptical of the President’s commitment to fulfilling his campaign promise of restoring the coconut levy funds after he vetoed the measure.

“Coconut farmers feel sidelined. The President promised that within six months, the funds would be made available to us, but nothing has been achieved on that end,” he said. “Nothing has changed.”