Peace in the Negros region was tested in a spate of killings that began late July this year and victimized public officials, police, and lawmakers alike. One of these victims was Canlaon City Barangay Captain Ernesto Posadas whose house was marked with the words “Mabuhay ang NPA (Long live the NPA),” and “traidor sa NPA (traitor to the NPA).”

Although the Communist Party of the Philippines-New People’s Army (CPP-NPA) has denied their involvement in the killings, the Philippine National Police’s (PNP) provincial hub in Negros Oriental named the group as one of their suspects. Amidst these allegations, the Commission on Human Rights stressed the need for an objective investigation into the Negros killings.

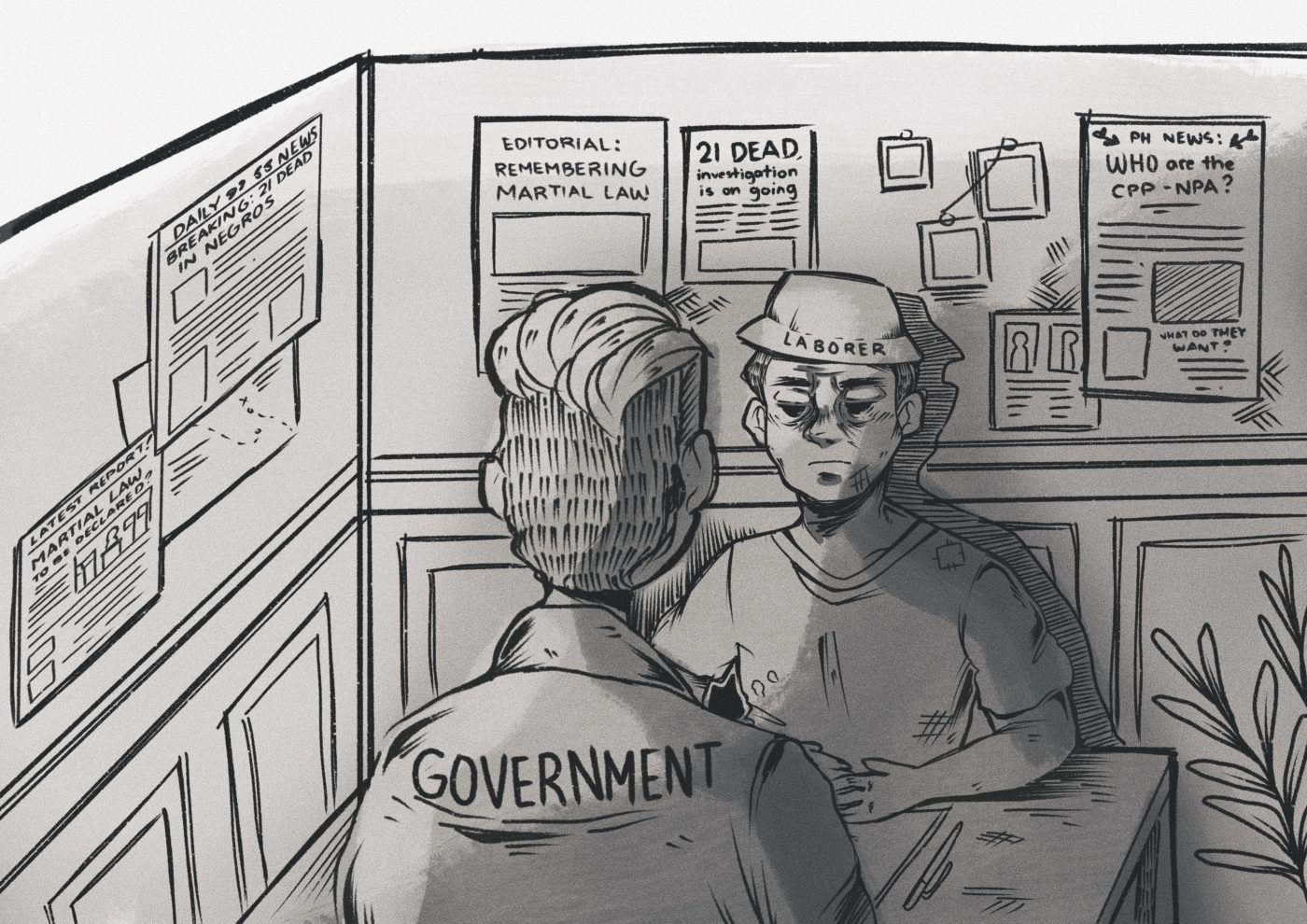

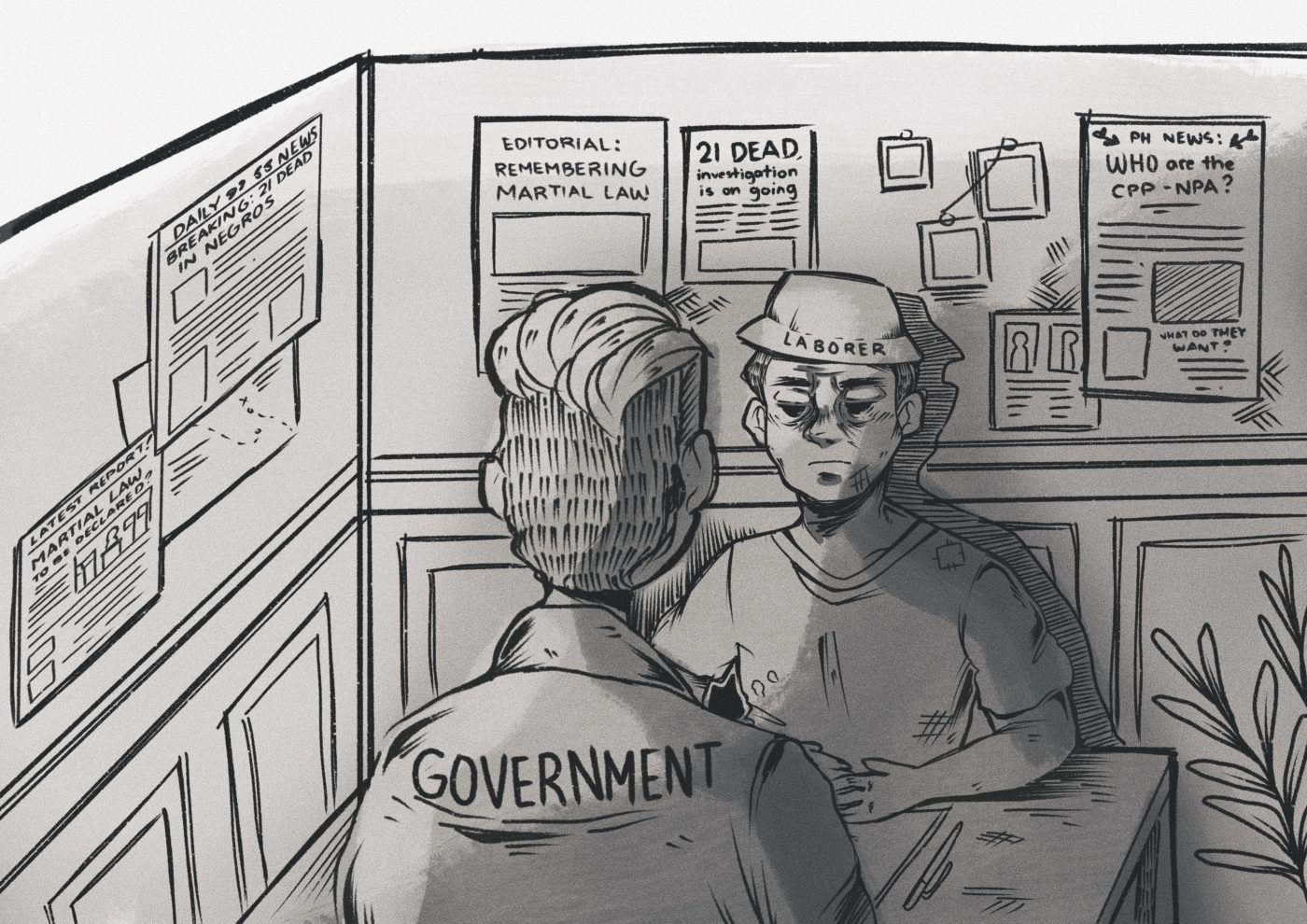

The PNP must first conduct an investigation to determine if the CPP-NPA is really behind the reported attacks. Pointing fingers at the NPA will only cause the group to lose trust in the government and decrease the possibility of non-violent negotiations.

Their four cents

The back and forth spates found its origins in Negros, a hotspot for CPP-NPA activity, when Jose Maria Sison founded the group in 1969, during the Marcos regime. Roberto Benedicto’s redistribution of the sugar industry’s wealth to Manila and abroad left farmers in Negros with little-to-no income when sugar’s world prices dropped to four cents per pound in 1984. Despite pressure from international entities like the World Bank to demonopolize the sugar bloc, Marcos turned a blind eye to these demands. As a result, dissatisfied sugar farmers who were overworked and underpaid banded together to form the CPP-NPA.

In 1972, Marcos implemented Martial Law, justifying his decision by stating that a sizeable number of communist insurgents—including the CPP-NPA—sought to overthrow the government. He also established a task force in 1984 for counterinsurgency efforts against the CPP-NPA in Negros by sending troops to combat the group. However, a report released by the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) noted that the said task force made no significant progress in putting a stop to rebel forces. Local politicians’ seeming disconnect to the realities of the working class have also allowed the CPP-NPA to form shadow governments in some areas of Negros.

Had Marcos brought the necessary reforms instead of implementing Martial Law and responding with violence, there would have been better, livable conditions for farmers. Enacting these reforms would have also encouraged productive dialogue about the needs of both sides.

Coming to a compromise

The government’s avoidance of negotiation continues with President Rodrigo Duterte’s permanent halt to peace talks with the CPP-NPA. Instead of dialogue, three Martial Law extensions in Mindanao have been implemented since May 2017 on the basis of rampant rebel activity that the administration associated with the CPP-NPA. So far these extensions have served as an ineffective solution to the long history of violent altercations between the two groups. Despite the Martial Law extensions, 193 clashes between the CPP-NPA and the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) have been reported in Mindanao in 2018 alone.

Repeated accusations against the CPP-NPA and the lack of government-initiated dialogue will only aggravate the situation in the region. If both parties are unable to find an avenue to voice out their grievances, issues such as land distribution—the cause of the rebellion years ago—will remain unresolved. If the government ceases to invest in accessible social service programs, positive dialogue, and non-violent negotiations, the CPP-NPA cycle of rebellion will only continue.

In the past, similar negotiation efforts have proven to be successful. A 2015 journal from Princeton University states that negotiations between governments and rebel groups are proven to result in peace if there is a tangible exchange between two parties. An example would be negotiations between the United Kingdom (UK) and the Irish Republican Army, a rebel group that fought to retake the British province of Northern Ireland. After 30 years of violence, negotiation between the two parties resulted in the Good Friday Agreement, a bond that allowed Northern Ireland to remain in the UK as long as its residents are allowed to select their country of residency.

At the end of the day, the lack of peace in the region is rooted in grievances over workers’ rights. Although the country’s working class deserve equal opportunities, many continue to struggle and, rightfully, hold the government accountable for their plight. Listening to the workers and their concerns will not only help resolve issues of land reform and fair wages in Negros, but also put an end to the very resentment that started the armed conflict.