IN MARCH, dangerously low water levels in La Mesa Dam caused a water shortage that gripped Metro Manila. Initially hitting the east zone covered by the private water concessionaire Manila Water, the crisis spread across the metropolis as water levels in Angat Dam dropped to critical. After four months of supply interruptions, the crisis continues to persist.

Various factors were attributed to the crisis like the increase in Metro Manila’s population. The east zone, consisting of Pasig, Marikina, Taguig, Quezon City and parts of Rizal, has a demand of 1,740 million liters per day (MLD). This demand has surpassed Manila Water’s 1,600 MLD allocation from Angat Dam. In fact, the company has been facing a water deficit since 2016, which it makes up for by drawing water from the La Mesa reservoir. El Niño and a weak southwest monsoon have also brought light rains that have failed to replenish water levels in both dams.

Manila Water said that El Niño only “aggravated” the problem. This delayed projects like the Kaliwa Dam and Cardona Treatment Plant initiatives. In light of this crisis, party-list group Bayan Muna, politicians, and some organizations pointed out the concessionaires’ failure to expand their service capabilities, and called for the renationalization of water services.

Taking back control

In June, congressmen such as Anakpawis party-list Representative Ariel Casilao and Bayan Muna party-list Representative Carlos Zarate urged the state to take back control of the private water services. Casilao and Zarate argued that Manila Water and Maynilad have failed to greatly improve their services despite having accumulated large sums of profit.

Casilao pointed out Ayala-controlled Manila Water’s earnings, which totaled a net profit of Php 6.5 billion in 2018, and juxtaposed this with their “deteriorating quality of service.” “The quality of their service should be proportionate [to] their profits,” he said.

Bayan Muna Chairman Neri Colmenares also criticized the companies for failing to uphold their service obligations to the public.

“Panahon na para i-abandon na ang privatization policy at ang Maynilad at Manila Water ibalik na ‘yan sa gobyerno at sa taong bayan.” Colmenares stated in a taped interview with Inquirer.net.

(It’s time to abandon the privatization policy. Maynilad and Manila Water should be returned to the government and to the people.)

Colmenares added that both companies failed to discuss ways to mitigate the effects of El Niño on water supply with the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewage System (MWSS) and National Water Resource Board (NWRB), which are responsible for regulating water resources and maintaining the operation of the waterworks system.

State responsibility

While many have criticized the water concessionaires’ role in mitigating the effects of the crisis, a working paper entitled Anatomy of a Working Crisis (2019) written by Ayn Torres and Dean Ronald Mendoza, PhD of the Ateneo School of Government (ASoG) discussed the state’s failure in strongly and efficiently regulating the concessionaires.

“One big part is better coordination and stronger inter-agency convergence,” the researchers stated. The government admitted in March that it needed to organize and redefine agencies that deal with water in order to better sort accountability.

Torres and Mendoza also highlighted how the MWSS could have “taken a stronger role in oversight.” They argued that the regulator has a “very soft relationship” with the water companies, and lacks a tougher stance on imposing authority and enforcing regulations.

In mid-March, MWSS asserted that it had no power to impose a fine against Manila Water. However, on April 24 it announced that it was fining the company Php 1.134 billion for failing to hold up to its obligation of providing 24-hour water supply. Former University of the Philippines Economics Professor Raul Fabella criticized the statement, claiming that MWSS was trying to cover up its “incompetence” by using Manila Water as a “scapegoat.”

Manila Water maintained that the company is not the “root cause” of the crisis, pointing rather to the lack of new water sources. This brings up the issue of ambiguity in the mandates of the concessionaire and the state regulator, as Section 5.1.1 of the concession agreement indicates that it is the obligation of the concessionaire—or the private company—to ensure new water sources. However, according to the state regulator’s website, it is the MWSS’s task to find these new sources.

Keeping it private

Some large business groups, composed of various corporate heads and economic managers, expressed their support for the privatization of water services. In a joint statement, the Joint Foreign Chambers of the Philippines & Philippine Business Groups (JFC-PBG), the Makati Business Club (MBC), and other corporations noted that water services have improved in the past 20 years of privatization.

“MBC reiterates its confidence in public-private partnerships in general and, in particular, the privatization of Manila’s water system,” the group stated on their website.

Similarly, Torres and Mendoza concluded in their working paper that privatization is still a better option in contrast to state-run water services, “since the private sector can still do distribution more efficiently.” However, they reiterated the need for a stronger state regulator to overlook the private sector to ensure that companies perform efficiently and prioritize the people’s interests.

As of June, the Malacañang stated that it will continue looking into the possibility of taking back control of private water services. For now, one of the Philippine government’s options is to reorganize its current agencies, determine accountability, and strengthen state oversight over private water services. Though whether water utilities should be under private or national control is still up for debate, this crisis serves as a wake-up call for both the government and private sector to further explore long-term solutions in water distribution.

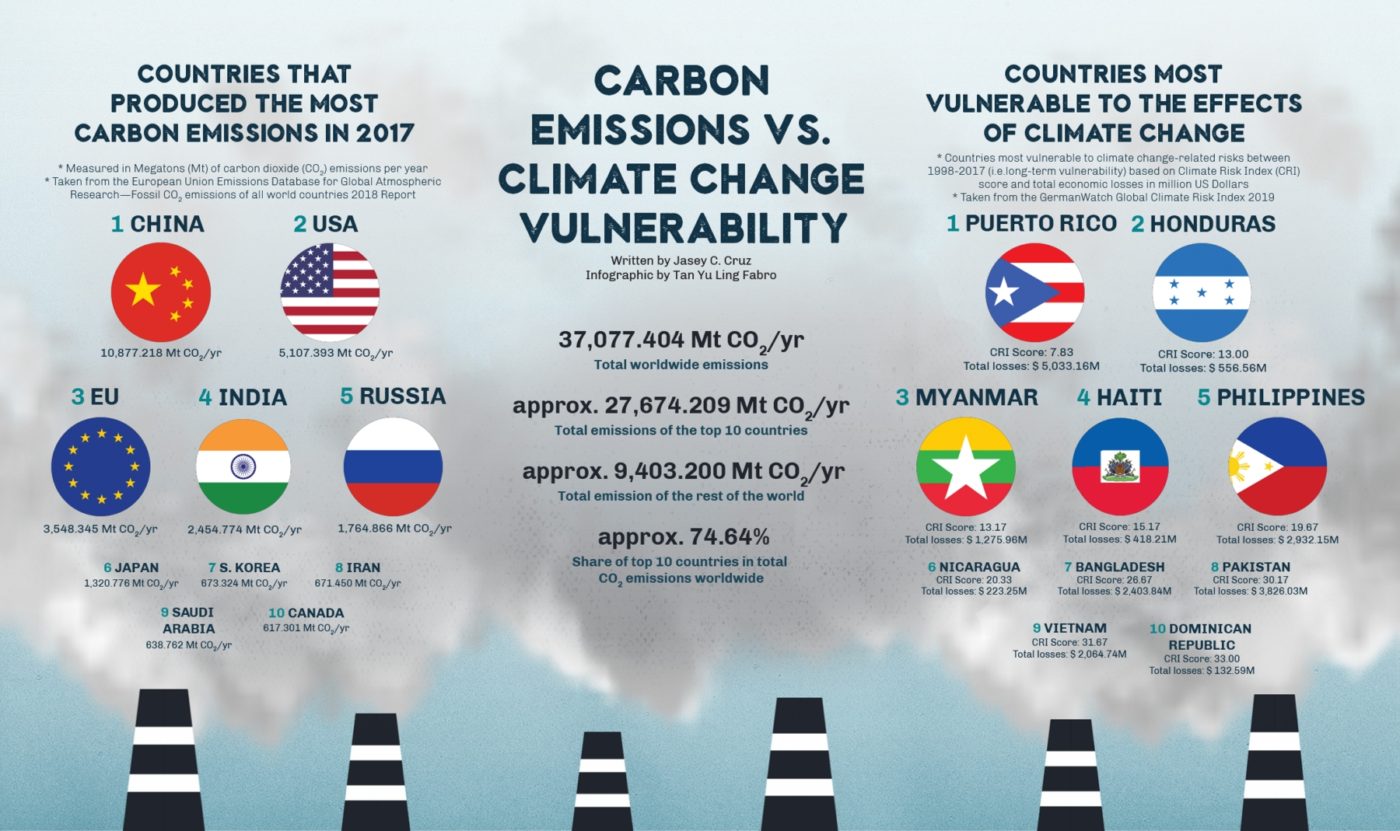

Infographic by Tan Yu Ling Fabro