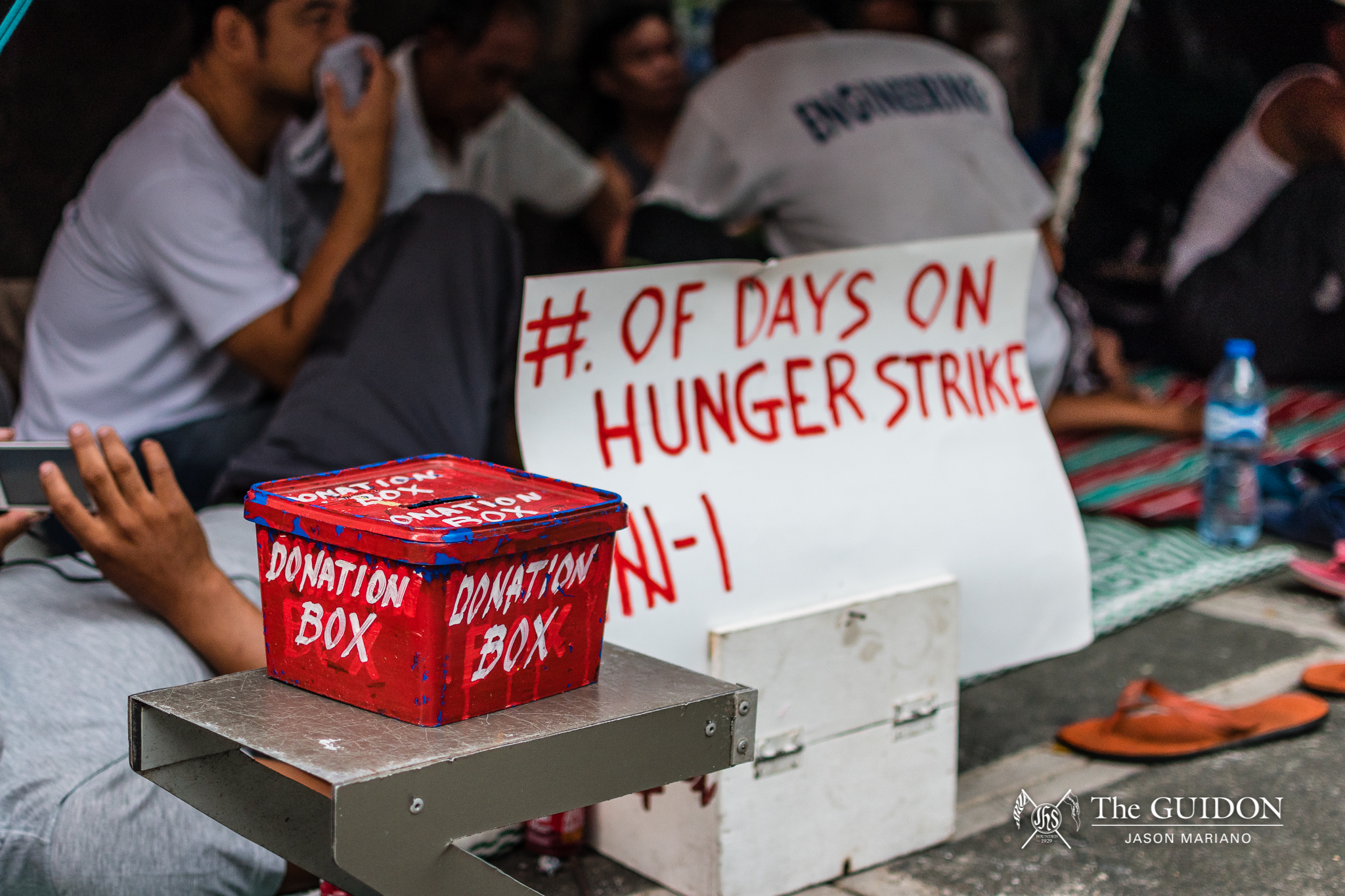

ON OCTOBER 5, 2018, Pacific Plaza Towers’ workers whose contracts were terminated three months prior instigated a hunger strike outside the premises of the condominiums in Bonifacio Global City. These workers, comprised of both regular and contractual employees, reported cases of mistreatment and wrongful termination. Aside from this, they claimed that they were treated as if “they were thieves.” Majority of those who participated in the strike are members of workers’ union The Pacific Plaza United Action of Labor. The Pacific Plaza Towers management has refused to extensively comment on the issue, having caused difficulty in media coverage. Since its formalization in July, the union has expanded its membership to include labor activists and students.

Despite the public’s increasing support of unions and heightening calls for action, as seen by students and labor activists joining the rally in Pacific Plaza, no resolutions have been made as the management stresses that the union fails to provide sufficient evidence linking the condominium to labor violations. Meanwhile, the workers found support in labor group Bukluran ng mga Manggagawang Pilipino (BMP), which is comprised of local unions and militant workers. BMP has attempted to negotiate a middle ground between The Pacific Plaza United Action of Labor and the condominium management in the legal aspects.

Other prominent worker strikes held were those led by employees from popular fast food company Jollibee Foods Corporation and leading condiments producer NutriAsia, Inc., which took place earlier in 2018. In April, DOLE released a list of companies suspected to be engaging in labor-only contracting, with Jollibee Foods Corporation (JFC) topping the list with an estimate of 14,960 affected workers. Consequently, DOLE ordered the company to regularize over 6,000 workers in its ongoing campaign against contractualization. JFC initially attempted to appeal DOLE’s order of regularization, but chairman Tony Tan Caktiong eventually claimed two months later that contractualization no longer existed within fast food chains, let alone in the Philippines—much to the dismay of labor group Sentro ng mga Nagkakaisa at Progresibong Manggagawa (SENTRO).

In an interview with Rappler, Jornell Quiza, a worker who was hired by contractor B-Mirk Enterprise spoke of his experience working for NutriAsia. He claimed he earned a measly wage of Php 380 a day and often resorted to working overtime to make ends meet. He also shared that when other workers also hired by B-Mirk Enterprise organized a union in April, they were terminated from their jobs. In a strike that was instigated in July, NutriAsia workers and their supporters were dispersed violently by authorities from the company and other police forces. Documentation of these acts made several rounds on social media and led to public outrage.

A climate of impunity

Labor movements are not new to the country’s political landscape. In fact, mobilizations grounded on the forwarding of workers’ rights have consistently played a vital role in shaping the nation’s current democratic framework, the most notable example being the contributions made by the organized Left in ousting the Marcos dictatorship. However, the aforementioned cases offer valuable lessons due to the nature and timing of their emergence, as well as the means by which they were quelled. SENTRO Secretary-General Josua Mata, notes that the recent upsurge of union demonstrations emanate from the complications generated by the climate of impunity brought forth by the current administration.

President Rodrigo Duterte’s ascendance to power was driven by a platform centered on inducing radical change through a combination of hardline stances on criminality with somewhat anti-establishment proposals. This strategy attracted voters across the political spectrum as Abinales and Claudio note that Duterte’s politics draws its strengths from both Left and Right-wing ideologies. Upon assuming office, Duterte immediately sought to actualize his left-leaning agenda by attempting to end contractualization. During his first State of the Nation Address (SONA), the President implored Congress to immediately work on a bill to end contractualization. In succeeding announcements, he had threatened to close the firms which refuse to comply with his orders. Over two years since his inauguration, it has become apparent that the President has failed to deliver on his promises. Mata suggests that burgeoning workers’ movements surfaced as an expression of discontent within the labor sector.

The working class’ disillusionment intensified when DOLE issued D.O. 174, which, despite criminalizing the practice of labor-only contracting, legitimized the trilateral structure—a mechanism that, as Mata suggests, reinforces contractualization by allowing employers to indirectly hire laborers through agencies. Duterte further incited the labor sector’s rage after signing Executive Order 51, an obsolete compliance order which corporations can easily circumvent via the trilateral structure.

In addition to the absence of effective legislation, Mata cited an incompetent bureaucracy plagued by corruption as another impediment towards significant labor reform. Mata highlighted that DOLE is incapable of effectively developing and executing labor reforms. He added that this is most notably manifested by the department’s failure to regularize an estimated 125,000 workers in 2017 despite attempting to do so for more than two years. Furthermore, labor organizations have accused Duterte of exaggerating his claim of regularizing over 300,000 workers earlier this year.

Mata concluded that these protests differ from prior mobilizations because of the vicious forms of repression they have encountered. He attributed the increasingly violent methods used against protesters to the war on drugs, specifically the atmosphere of lawlessness it projects. In garnering massive support from the President, authorities have been more confident in utilizing tactics to imply false culpability such as planting evidence. A study by Danilo Reyes suggests that an underlying effect of the drug war is its capacity to introduce social decay in how citizens have been desensitized from the rampant atrocities taking place, thereby normalizing otherwise problematic activities such as summary execution and vigilante killings.

Mata points out that this pattern has been integrated to the labor sector as well. The forceful dispersal of the strikes in NutriAsia bore witness to the use of similar gambits when officers allegedly found some union members to be carrying armaments and packets of shabu. In fact, Mata claims that labor unions have not faced this degree of brutality since Martial Law. Furthermore, he links the worsening means of suppression to the President’s rhetoric promoting extralegal methods which in turn empowers corporations by eliminating weariness for possible sanctions.

Fighting for change

In the country’s current political context, what ties all the worker strikes together is their struggle for the recognition of their human rights. “Human rights is a holistic thing,” Mata explained, pointing out that the workers’ union’s fight for just treatment as members of the Philippine workforce will never gain traction until people become more concerned with the essence of human rights.

In an interview with Rappler, Victor Vallega, a plumber who worked for the Pacific Plaza said, “Napakasimple lang naman ng hinihingi namin. Ibalik nila kami sa trabaho. Parang pinatay na rin nila kami eh. Kaya ito, hindi kami titigil sa hunger strike hangga’t hindi nila kami ginagawang regular.”

(What we’re asking for is simple—give us back our jobs. It’s almost as if they killed us. Now, we won’t stop our hunger strike until they regularize us.)

Mata admits that current labor laws in the Philippines are in need of revisions and stricter government intervention, as these continue to hinder workers’ unions from achieving their goal of regularization and overcoming the age old problem of contractualization. “The law in itself is flawed and then there’s bad implementation, Both would have to change.” Despite the untimely political setting, Mata says that this newfound sense of the climate invigorates the workers to fight as it presents itself as an opportunity for change. “Labor unions would push on and become angrier. Not flourish as much as it should until the imposition of human rights.”

What do you think about this story? Send your comments and suggestions here: tgdn.co/2ZqqodZ