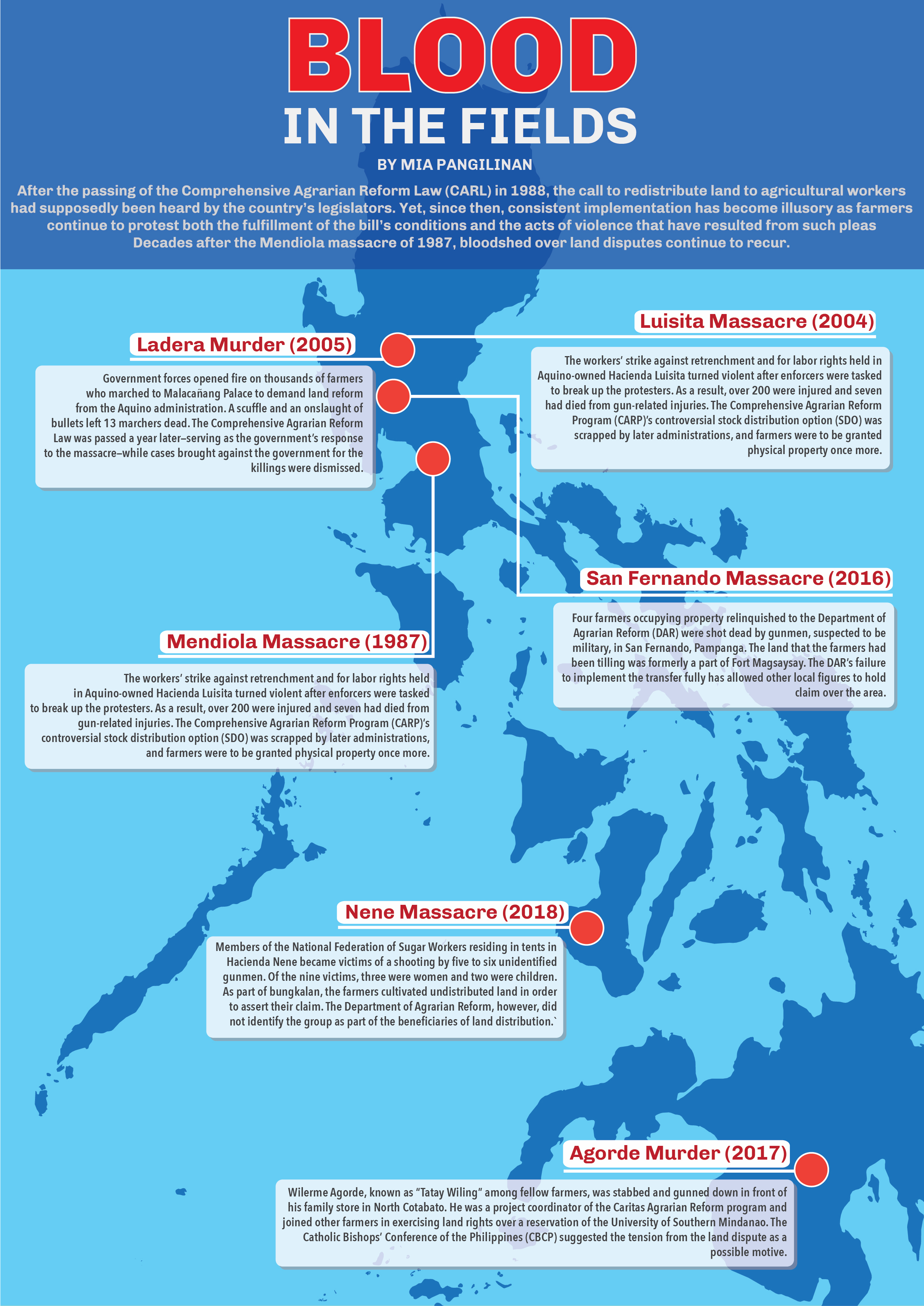

THE MASSACRE of nine farmers last October 20 at Hacienda Nene in Barangay Bulanon, Sagay City, Negros Occidental is the latest in a long line of agrarian reform-related incidents of violence in the Philippines. Of the nine victims, four were women, two were minors, and all were part of the National Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW). The 40 gunmen who attacked the farmers remain unidentified, however Negros Occidental Governor Alfredo Marañon Jr has offered a Php 500,000 reward through the Sagay Police Station for any information that could lead to the arrest of the assailants.

In an interview with Radio DZMM, Sagay Police Chief Inspector Roberto Mansueto reported that local police are looking into land distribution disputes as a possible motive. Initial investigations found that the farmers’ lease contract with Carmen Tolentino, the hacienda owner, is set to end next year. DZMM also interviewed Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) Secretary John Castriciones, who revealed that the farmers were not beneficiaries of land distribution programs.

In a statement given by Presidential Spokesperson Salvador Panelo to Inquirer News, Malacañang condemned the events of the Hacienda Nene massacre “in the strongest possible terms.” Earlier this year, Inquirer also reported that President Rodrigo Duterte himself called for a “renaissance” of land reform in the Philippines. The administration plans to distribute the remaining 500,000 hectares of land covered by the now-terminated Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program Extensions with Reform (CARPER) Law.

Beneath the surface

Despite the current administration’s desire to expedite the process of land redistribution, several hurdles still remain in place. As a reaction to the government’s slow processing of land distribution grants, for instance, farmers began bungkalan operations under the banner of the NFSW. In a piece published by The Philippine Star, NFSW reportedly explained that bungkalan operations happen when “farmers militantly occupy idle lands and collectively cultivate these lands in order to make [them] productive. Bungkalan reflects the failure of the government’s land reform program and the landlords’ refusal to distribute land to the tillers.”

In an interview with GMA News, a niece of one of the victims recounted that the farmers choose to join the NFSW because they were under the impression that they would be given their own plots of land. The unlawful seizure of agricultural property conducted by farmers under the NFSW was intended to be a show of dissatisfaction with the current land reform policies of the government. It is evident that the tillers, especially those whose plots are still under the hacienda system, are unable to feel the benefits of the decades’ worth of land reform legislation.

These massacres prove that bungkalan operations have endangered the lives of farmers. The gruesome Hacienda Nene mass murder is only the latest in a series of attacks against farmers caught in disputes with the landowning elite. In a compendium published by Rappler, incidents like these were reported to have occurred as early as 1950. Arguably, the most infamous altercation listed was the murder of seven farmers in Hacienda Luisita in 2004. Its notoriety stems mainly from the connection the landowners had to late former president Corazon C. Aquino. Aquino’s paternal family, the influential Cojuangcos of Tarlac, acquired the plantation in the 1950s. The former president personally held shares in the land until 1987, before she bequeathed her holdings to her children and various charities upon assuming the presidency.

The forfeiture of her interests in the land was quite timely. Barely a year into her tenure, she signed into law the the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP), the predecessor of CARPER. This program tackled the issue of land reform mainly by redistributing vast tracts of land from the landed minority to the hands of farmers who, up until then, had merely possessed tenancy rights and not full ownership of the land they tilled. Aided by extensions signed into law during the Ramos and Arroyo administrations, Aquino’s efforts served as an impetus for the mass reorganization of land ownership that continues to this day.

The progress so far

When CARP and its extension, CARPER, were enacted, each mandated that the redistribution process be completed within a decade, totalling 20 years. After the failure to meet both deadlines in 1998 and 2008, former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo signed legislation that re-extended the program and gave the government until 2014 to finish the process. However, this deadline was rendered pointless by a caveat include in this 2009 law, which allowed cases that remained unresolved by the end of the five-year period to be processed indefinitely until they were settled. This left the government without any real time limit on the process of transferring tens of thousands of hectares of land in cases that remain pending.

The unrestricted period granted to the government by the latest law ran the risk of diminishing the sense of urgency and public visibility that an impending deadline would have given to the program. Yet, in a Philippine Institute for Development Studies report from December 2017, it was found that over 4.8 million hectares of non-private agricultural land have been distributed to over 2.8 million farmers, over half of the farming households nationwide, since the program began in 1988. After surpassing the halfway point, the DAR only has 30 percent of non-owner-cultivated lands left to redistribute.

Despite the unprecedented volume of land transfers, the implementation of agrarian reform policies have been persistently marred by violent incidents like that of the Hacienda Nene massacre. Confrontations are, at times, unavoidable in the land reform process. Reluctant landowners, in an effort to defend their own interests, have been the most troublesome obstacles preventing the complete realization of this program. Unfortunately, it is the farmers that are harmed the most by the delays in the implementation of land redistribution laws.

The expenses tied to purchasing land under the guidelines of CARP is another hurdle which prevents farmers from claiming ownership over the lands which they cultivate. In 2016, former DAR Secretary Rafael Mariano lobbied for Congress to legislate a bill which would expand the coverage of land under CARP, while also making it free for farmers to receive ownership of these parcels. Mariano argued that only 25 percent of CARP beneficiaries have been able to fully pay for their lands. He also pointed out that over 120,000 beneficiaries were unable to pay even for their monthly amortization.

Clearly, there is a discrepancy between existing land reform policies and the actual capabilities of the farmers. Prior laws, particularly CARP, were comprehensive in terms of outlining beneficiaries and providing strict timelines for the distribution of parcels. However, these guidelines were not met because of uncooperative landowners and high costs of purchasing land. Ultimately, a large percentage of farmers, especially smallholders and subsistence farmers, will not be able to pay for the full value of the land which they cultivate.