President Donald Trump’s trade war with China goes beyond trade deficits—it is a bitter struggle between a well-established superpower and its rising challenger, escalating to an extent that some call the onset of a new Cold War. Nevertheless, Trump’s current headline-grabbing trade war with China stems from his desire to cut the United States’ (US) trade deficit with China. In fact, he has accused the Chinese of unfair trading practices which he claims have hurt the US economy. As of July 2018, the US trade deficit with China stands at $222 billion, with a high of $375 billion last year. He also sees tariffs on tech and clothing products to be the answer towards China’s alleged intellectual property theft. Interestingly, Trump believes that engaging in a trade war is rather “easy,” and a way to “win big.”

According to International Monetary Fund (IMF) Chief Economist Maurice Obstfeld’s interview with Bloomberg, an escalation of trade war tariffs—and consequently the rendering of threatened trade barriers into reality—could lead to a decrease in global output levels by 0.5% in 2020. Moreover, IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde echoes that reducing trade or erecting additional barriers won’t generate any winners, she said in an interview with Argentine daily La Nacion Lagarde. Lagarde also believes that “it is always the poor people that suffer the most as a result of those barriers or trade tariffs.”

In an interview with the Financial Times, Lagarde also warns that emerging markets will experience a shock from the intensifying US-China trade war. Consequently, the currency crises that Turkey and Argentina are experiencing could spread to other emerging markets. After all, a measurable slowdown on China’s growth could trigger vulnerabilities in Asian economies, whose supply chains are intricately linked to China. Indeed, 30% of the value of Chinese exports to America originates from third-party countries.

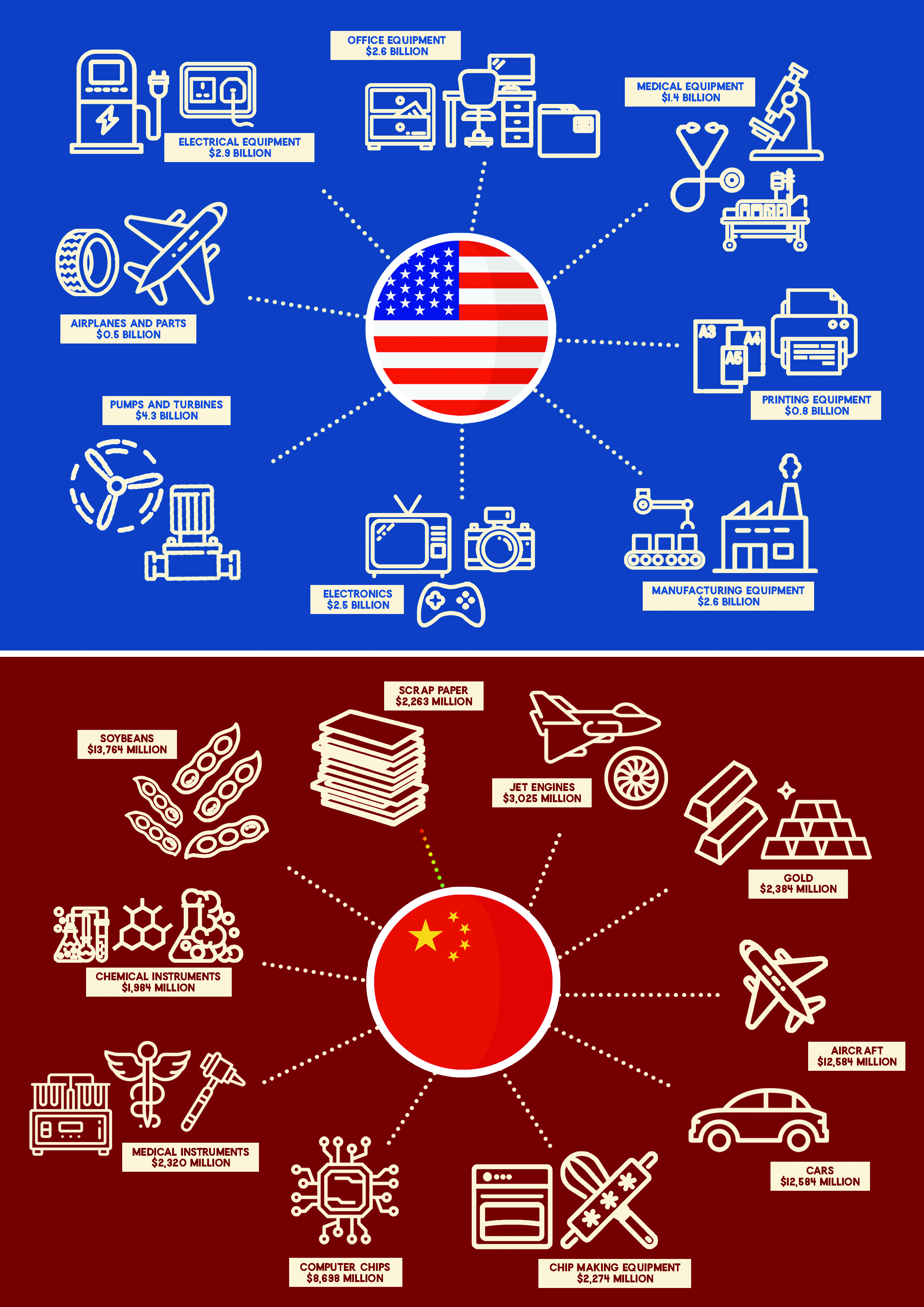

As for China, the country sees the trade conflict as part of Washington’s design to temper its rise to greater heights. China, however, may not have as much firepower as the US to retaliate. After all, China only imported about $131 billion in U.S. exports last year, while the U.S. imported $506 billion worth of Chinese exports. This means the Chinese side will eventually run out of U.S. exports to impose tariffs on, as noted by Scott Anderson, chief economist of Bank of the West. Consequently, China will find alternative ways to retaliate, most likely through increasing red-tape that will make it harder for American firms to operate in the mainland.

Economic warfare: the new normal

The US has slapped two rounds of tariffs on Chinese goods so far. The initial tariffs were placed on $50 B worth of Chinese exports. The latest round of tariffs was implemented last September 24 on $200 billion worth of Chinese products—such as food, minerals, and consumer goods—bringing the total amount of tariffs to $250 billion. At the height of this conflict, Trump threatened to slap tariffs on all $500 billion of Chinese goods, signifying that he is prepared to go all-out to exact concessions from China. Consequently, even blue chip companies such as Apple are wary of a rise in production costs should the next round of tariffs be imposed, especially since their manufacturing is based in China. Consequently, Zhang Zhiwei—Deutsche Bank’s chief economist for China—says that China should now focus on retaining supply chains that link and support world trade.

In response, China also implemented $60 billion of counter-tariffs on American liquefied gas, machinery, and electric equipment last September 24. This brings their total tariffs applied to US goods to $110 billion. Beyond tariffs, however, is the mainland’s focus on the Made in China 2025 Plan, which encourages the expansion and improvement of Chinese manufacturing companies, focusing on high-value technology which will ideally pull them up to western levels. Unsurprisingly, the US government considers this new plan to be harmful to companies both inside and outside of the US. Trump’s confrontational foreign policy approach is also helping to strengthen Beijing’s ambition to internationalize the Yuan. This leads global institutional and government investors to believe that a protracted trade war could bring about some long-desired changes, and consequently to more investments, in China’s highly regulated financial markets.

Despite China enjoying the trade surplus, a team of economists led by Haibin Zhu at JPMorgan Chase & Co. believe that the trade war with the US may cost the country 700,000 jobs. The job loss will certainly occur if China retaliates by devaluing the Yuan by 5%, along with adding tariffs on US goods. Zhu and his team also believe that should China choose not to retaliate, 3,000,000 people could lose their jobs, they said on a research note last September 11, 2018. China is thus backed into a lose-lose situation, but must nevertheless take action, lest they lose face on the grand stage.

What does this mean for the Philippines?

Amidst downward economic trends and rising inflation, a trade war between two of the Philippines’ largest trading partners seems like a cause for concern. However, Budget Secretary Benjamin Diokno claims that it is not a concern for the Philippines as it is not an export-oriented market. In the same media briefing, Secretary Diokno says that the trade war might benefit the Philippine economy, especially because neither country has plans on imposing tariffs on Philippine exports.

Economics lecturer Neil Adrian Cabiles, PhD stated in a forum on Philippine-Chinese cooperation amidst the US-China trade war that the Philippines can stand to gain by filling in the gaps created by the export tariffs. To do this, the Philippines must develop sectors with high competitiveness, like that of textiles and electronics, in order to keep up with the import needs of other countries.

In the same forum, Chinese studies lecturer Lucio Pitlo III, MA highlighted the importance of manufacturing higher value goods which cannot easily be substituted, such as aircraft parts and semiconductors. Both Cabiles and Pitlo believe that it is essential for the Philippines to invest in the education and skills of its people in order to create a competitive labor force. Pitlo recommends greater focus on Science, Technology, Education, and Math (STEM) studies that will help increase production of high value technology. Pitlo also stressed the necessity of attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the Philippines to fund the development of local manufacturing sectors. FDI is also one of the country’s most significant drivers for economic growth.

With the rising tariffs, Chinese manufacturing companies are migrating to South East Asian countries with cheaper labor costs. This presents the Philippines with an opportunity to be a manufacturing base for these foreign investors. As Secretary Diokno claims, goods exported from the Philippines do not have additional tariffs placed upon them. This arrangement allows Chinese manufacturers to escape US tariffs, while also benefiting the Philippine labor market.

While expert projections are optimistic, these beneficial outcomes can only happen if the Philippines commits itself to the development of its industries. Without proper funding, or proper education, local markets will remain stagnant, and may even suffer from supply chain disruptions brought about by the rising tariffs.