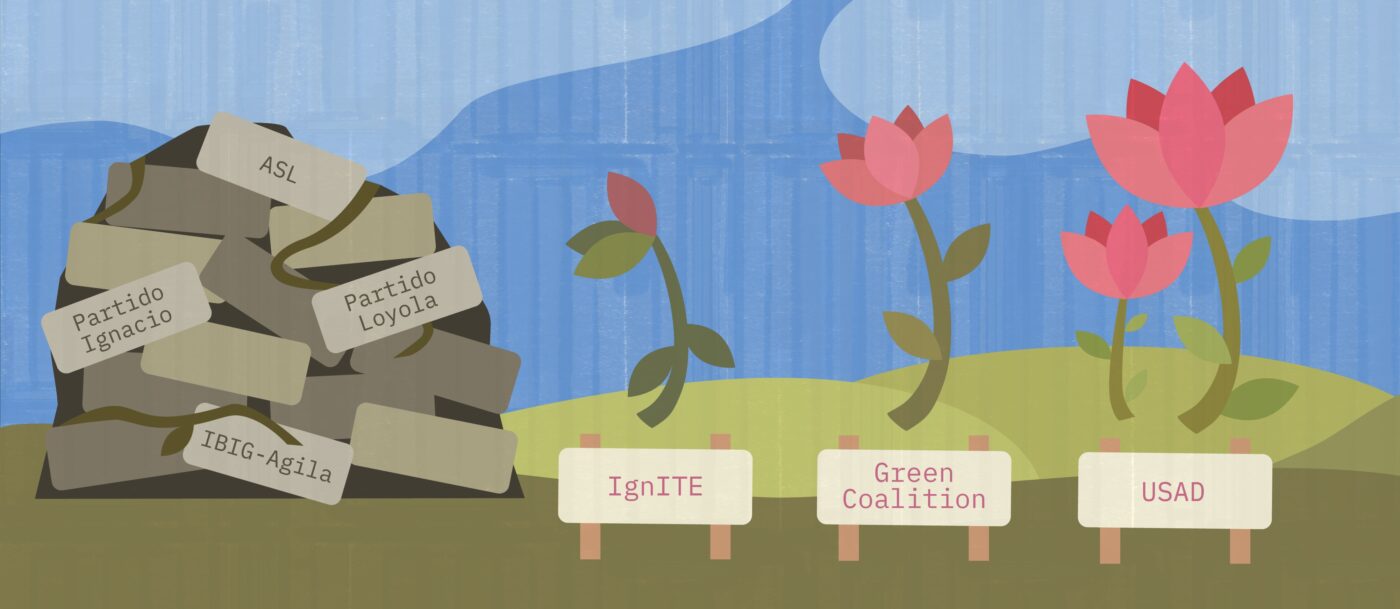

Over the last few years, failures of election, political party disbandments, and criticisms thrown from many different fronts have left the Ateneo’s political landscape in disarray.

Even as Sanggunian officers and members of different political parties continue to put effort into reinforcing and revitalizing the political scene, the burdens of the past still inevitably haunt the present. Going as far back as the late 2000s, the state of party politics in the Ateneo had already begun to shape trends that would eventually lead to the situation we know today.

Rise and fall

The political parties of the past had their fair share of complications, especially with the frequent occurrences of major rebrandings, mergers, and abrupt dissolutions just a few years into a party’s existence.

Founded in 2003, Partido Agila was one of the most dominant political parties at the time. It stood strong for nearly 5 years until the party announced in early 2008 that it would be merging with a newly created party in that of IsaBuhayIsaGawa (IBIG) to form IBIG-Agila. It was the former’s last-ditch effort to recover from its loss of momentum throughout the years.

Just as with any kind of merger, one can reasonably expect there to be some friction, as rarely are political parties able to merge seamlessly. Unfortunately, this would prove to be a major problem as the political powerhouse did not last very long. The internal turmoil within the party peaked during its third year, and not too long after their efforts to rethink the party’s identity, they announced their disbandment to much dismay.

This is one of the earliest examples of what would eventually become a longstanding trend in party politics, as many of the political parties that came and went from then on all share the same characteristic of being relatively short-lived in nature.

For instance, Partido League of Atenean Youth for Liberal Advocacy is one of the two parties that emerged immediately after IBIG-Agila’s dissolution, but its legacy ended soon after its inception.

In a similar vein, IBIG-Agila rival Partido Ignacio eventually also saw its demise after a few years of prominence, which bolstered the budding Alliance of Student Leaders (ASL) coalition. However, after some years of dabbling in the scene, ASL ultimately opted not to pursue political party accreditation.

The Ignatian Initiative and Transformative Empowerment (IgnITE) Movement is another such party, and while it was proving itself to be one of the stalwarts that showed some lasting potential, the party halted its five year run last February 15, 2017.

The most recent political group to come forth is the Green Coalition, which was a small group of aspiring officers brought together by Sanggunian Vice President Niels Nable to compete strictly as a coalition in the 2018 elections. While Nable and some other members express some interest in elevating the group’s status to that of a political party, the likelihood of this happening is slim despite the coalition’s success.

“[With] the weight of work I have as Sanggunian Vice President until March [2019], and the needed manpower to create a political party, […] I think transforming Green Coalition to ‘Green Party’ is improbable as of now,” he says.

Finally, there is The Union of Students for the Advancement of Democracy (USAD), which burst onto the scene as the Christian Union for Socialist and Democratic Advancement (CRUSADA) back when IBIG-Agila was the dominant party. It has since managed to outlast not just this prominent rival, but all the other parties over the last few years as well. At present, it remains the sole political party on campus.

Cascading problems

With this dynamic, the Ateneo’s campus politics sits at a peculiar spot amongst all others. In the national government, traditional party politics involves the active participation of an entire gamut of parties that have been around for decades. Sitting closer to home, the University of the Philippines Diliman features its big three parties which have been duking it out for many years now. Nevertheless, while different, the distinct lack of established and longstanding political parties in the Ateneo does not necessarily translate into a problem immediately.

“The primary role of political parties in Ateneo is to make the student body ‘political’” as Nable insists. Likewise, Ateneo Commission on Elections (COMELEC) Chairman Carl Garcia poses a similar take: “Political groups are a way for students to collectively give a voice to different concerns and raise awareness among the Ateneo community.” With these definitions, it is evident that even if there are only a few parties present, tackling and engaging in dialogue about prevailing issues can and should still be possible.

However, looking further into the Ateneo’s party politics reveals that the current dynamic of short-lived political parties is driven not by cutthroat politicking or strong politicization, but by a set of major underlying problems. This reinforces the fact that it is very much detrimental to the health of campus politics, and USAD Premier Earl de los Santos identifies that the biggest issue at hand is that of the parties losing their identity.

“The problem is, historically, political parties [on] campus had found it difficult not only in asserting an identity, but also [facing] other challenges: the preservation and transmission of this identity, and connecting this identity to the everyday lived experience of its members amidst an ever-changing environment that perennially demands analysis and reflection,” he affirms.

Thus, it has been established that political parties are present to help tackle political issues and realities with respect to their own ideals, but principles that are weak, faulty, or even nonexistent, often lead to a party inevitably struggling to stand its ground.

IBIG-Agila saw mass resignations as a result of its failed restructuring efforts. In its twilight years, IgnITE foresaw its inability to evolve past its roots as a reactionary party, which eventually led it to disband. Many student coalitions have also lost steam and disappeared, and many more will follow suit so long as this issue goes on.

Moreover, while the absence of a prevailing identity or ideology eats at parties from the inside, the lack of engagement and opportunities for politicization kills their involvement with the rest of the student body. This stems from a variety of reasons, such as with people “[misinterpreting] political parties as a mere stepping stone for candidates with political ambitions in the Sanggunian,” de los Santos notes.

Garcia suggests that the strong organization culture in the Ateneo also plays a part in this, as he observes that “many students would rather focus on [the different advocacies] and the internals of their own orgs.” Even the 40-member quota imposed by COMELEC serves as an unlikely deterrent for aspiring political parties, which further shows that the level of involvement and traffic generated by campus politics is far from ideal.

Breaking the chain

These factors led to political parties being muted and largely unsustainable. Support from existing members dwindles as the parties fail to assert their own identity and advocacy, while the rest of the students simply look for alternatives in the form of organizations or even external groups such as the Kabataan Partylist, which founded its Katipunan chapter just recently.

Over the past few years many political groups have tried to take on the challenge of reinvigorating party politics. However, given how these problems have never failed to disrupt and dismantle, it is evident that they will simply persist unless existing and future parties step their game up significantly. Some form of radical change has to be brought onto the table, and there are many ways by which to do so.

“With all the social and political issues out there, I think it is of great importance that our student leaders be more open to hearing them and acting on all the concerns of the student body and not just the interests of the political groups they originated from,” suggests Garcia. Rethinking the internal affairs of political parties to make them more engaging, inclusive, and relatable is one of the ways to attract more attention and involvement from the student body.

On another note, “many [Ateneans] care about different issues such as labor rights, gender equality, [and] environmental protection, but there is really an urgent need to tackle these issues radically so that our efforts in addressing them are not low-impact and palliative,” says Nable. He proposes a three-pronged approach to the overhaul of political parties and how they function: “[Form] members politically through a well-crafted political formation program, expand their external network, and create effective marketing strategies that will encourage students to join them and be more politically active.”

Similarly, de los Santos highlights the need for broadening perceptions and reaching out to larger realities outside campus. “The political discourse, which during [USAD’s] founding years focused exclusively on student-centered projects, had also already elevated to questions of externalization. This, I believe, can set up a landscape where political parties can not only flourish and achieve further formalization, but also collaborate with student organizations within the campus,” he says.

Now or never

At the end of the day, it is easy to adopt the mindset that these discussions don’t mean much outside of the Ateneo. It is entirely possible to go about one’s student life completely shut out from outside affairs, but doing so will simply reinforce the negative stigma that Ateneans exist in a bubble. While many would claim that this is clearly not the case, we also need to walk the talk.

As problems from outside continue to bleed into the campus, the pressure to politicize is growing at an alarming rate, and the lackluster state of campus politics will no longer cut it. Political parties are supposed to be at the forefront of making sure that the student body is informed and well-equipped to tackle major issues and outside realities. The times call for present and future parties to cut the slack, do their job, and do it well.

Pullout quote: “It is of great importance that our student leaders be more open to […] acting on all the concerns of the student body and not just the interests of the political groups they originated from” – Garcia