Long before the likes of Versace and Gucci mixed fashion and the Catholic imagination, Filipino devotees have been adorning wood and ivory statues depicting saints, angels, Marian titles, and personages of the Trinity as an expression of their faith.

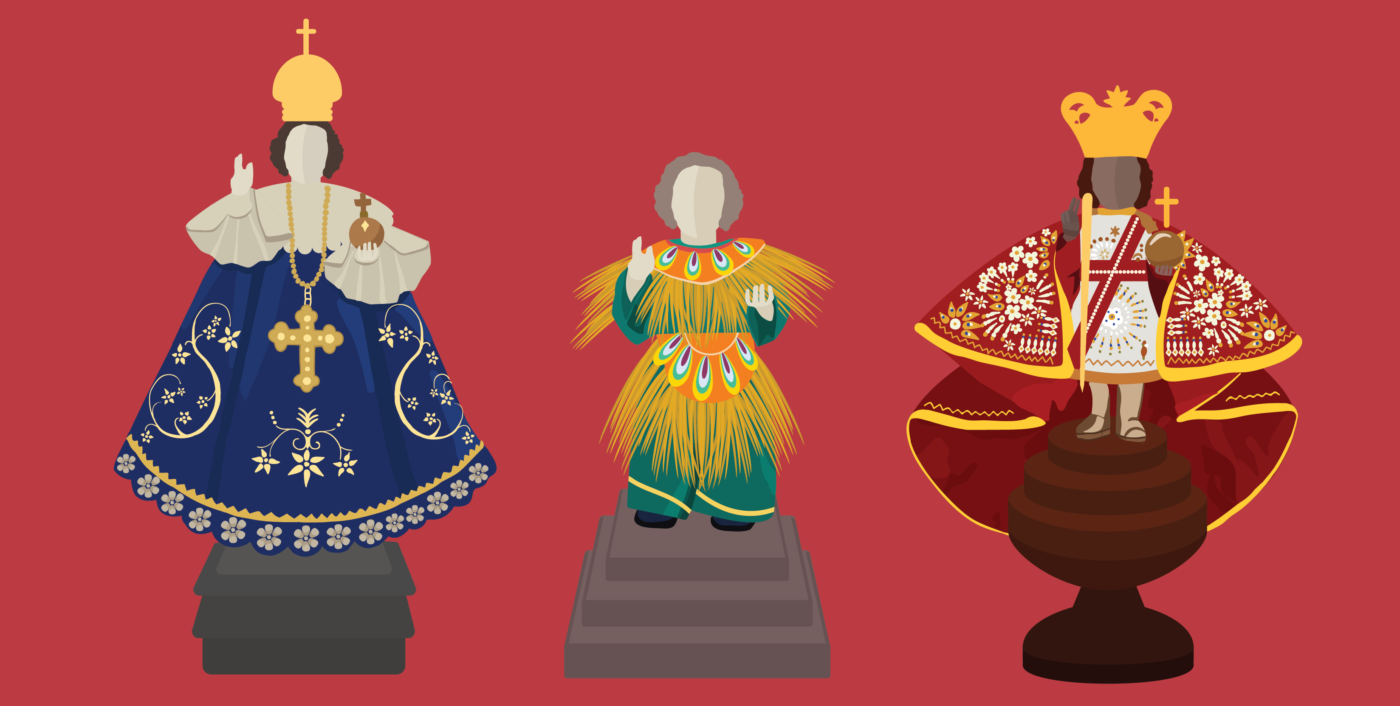

From santos dressed in Baroque, gold-embroidered vestments to those donning more exotic materials like feathers, piña, or even rags, santo couture is a diverse art form that blurs the boundaries between fashion and religion.

The santero tradition

The practice of caring for santos in the Philippines is rooted in its colonial past under Spanish rule, with the earliest record of a vested santo in the islands being the Santo Niño de Cebu, gifted by Ferdinand Magellan to Rajah Humabon’s consort in 1521.

The use of santos in Roman Catholicism originated earlier in Medieval Europe where they bedecked churches and home altars, serving as earthly representations of the divine. They later spread to the Americas and parts of Asia through Spanish, Portuguese, and French colonizers and missionaries who used them as gifts and catechismal aids to convert the local population.

Santos are a particularly vibrant tradition in parts of Latin America, such as Mexico and Cuba, the Southwestern United States, and the Philippines, where it has been preserved as a folk art.

Art historian and author Eloisa Hernandez, PhD, writes that “[Filipino] natives took to sculpture instantly” upon introduction from the Spaniards, remarking that as natives converted from animism to Catholicism, sculptures of saints slowly replaced carvings of anitos, nature spirits and deities.

There are two types of santos: bastidores, mannequins with changeable vestments and accessories, and detallados, statues with adornments painted on permanently. Escultoras refer to the craftspeople who make santos, burdaderos are those who make their adornments, while santeros or camareros (Spanish for “waiting staff”) are the custodians of santos who maintain and dress them.

A spectrum of santos

The bases for santos are traditionally made of either elephant ivory or wood, but the former has been restricted in the Philippines for newer creations. Today, santol remains a popular material as does batikuling, a prized hardwood known for its resistance to termites. Resin and fiberglass on the other hand are economical alternatives.

Santos range from small statuettes less than a foot in height, often kept as personal keepsakes, to life-size models and enormous monoliths, more common in church altars and use in processions.

But perhaps the diversity of santos is most seen in the clothing of bastidores where haute couture is commonplace among camareros new and old. When it comes to the Filipino santero tradition, centuries of inculturation have given rise to a multitude of representations of the Catholic celestial hierarchy.

There are traditional and lavish santos such as the Our Lady of La Naval de Manila, a depiction of the Marian title of the Holy Rosary, often called “The Grandest Marian Icon in the Philippines.” Made of solid ivory, the sculpture was commissioned by Spanish Governor-General Luis Pérez Dasmariñas in 1593 and made by an unnamed Chinese immigrant.

The 4’8” statue has an extensive collection of ornate regalia with pieces dating back to the 18th century. Adding to her collection are the ornaments fashioned from heirloom jewels, gemstones, golds, and silver that 310,000 individuals led by the University of Santo Tomas donated in celebration of the Lady’s 1907 canonical coronation, when Pope Pius X bestowed a crown to the image.

Located in Santo Domingo Church, Quezon City, Our Lady of La Naval de Manila is never seen without her massive crown and halo, golden and bejeweled, an intricate inuod (embroidered with gold bullion thread) garb, a gold scepter, and her ivory Child Jesus, crowned and dressed in a garb just as grandiose. A rosary with pearl beads, gold chains, and a gold cross drapes over her and Jesus’ hands, true to her Marian title.

Such elaborate and opulent decorations are characteristic of the Baroque style that emerged out of the Catholic Reformation—a movement that sought to counter Protestant simplification of art, music, and the liturgy—and flourished in the 17th and 18th centuries. Most of the santos in the Philippines are from this period.

In contrast, there are santos that take a more modest approach to representing the divine. These include the collection of saints of the Ateneo de Manila University. For instance, the image of Saint Stanislaus Kostka, SJ, exhibited in his namesake chapel in the Ateneo High School, wears the plain black robe of his order and a simple halo painted with faux gold.

Timoteo Ofrasio, SJ, a lecturer at the Loyola School of Theology and an expert in sacred art, says, “[The way Jesuits depict saints] is as simple as possible with not much ornamentation, the way they were in real life” in accordance with the Jesuit tradition.

There are also santos that conspicuously incorporate elements of Filipino culture in their garments. The Filipinized Blessed Virgin Mary and Child, created by Willy Layug, Presidential Merit Awardee on Ecclesiastical Art, is an example. The image was part of Pope Francis’ 2015 mass in Tacloban, which was ravaged by Typhoon Yolanda the previous year.

Made out of wood debris from the then-destroyed Palo Cathedral, the detallado depicts a Filipina Mary donning a white, gold-detailed baro, floral embroidered lavender saya, and a black veil, while she carries a Child Jesus holding a rosary and reaching for a child in the sea. The image deviates from traditional Catholic iconography, instead drawing from the faith of Filipinos amidst Yolanda.

Similarly, the Sinulog, Ati-Atihan, and Dinagyang, festivals dedicated to the Child Jesus, would often parade brown-skinned Santo Niños in traditional Baroque or, at times, native-inspired costumes. The latter would be made of straw, feathers, and banig akin to the flamboyant attires of parade dancers.

Then there are santos that are decidedly unorthodox. For example, devotees would bring all sorts of Santo Niños to the opening mass of Sinulog, including images of the Child Jesus dressed in curious ways. There are santos dressed in casual attire or as mariners, policemen, chefs, basketball athletes, and various professions. Some are even dressed as fictional characters, with superheroes like Captain America and Superman being particularly in vogue.

Vincenz Lois, a camarero, hagiographer, and the Ateneo Senior High School’s head of Christian Life Education, explains that Filipinos tend to be “whimsical” with the Santo Niño. “Sociologically, Filipinos treat the Santo Niño as their own child so they try to don [it] with familiar [or] comfortable clothing, […] things they can relate to more,” he elaborates.

The sacred and the profane

This practice of depicting santos in unconventional ways is a common form of popular religiosity among Filipino devotees. However, camareros and Church leaders alike have spoken out against such expressions of faith.

Rector of Don Bosco Technical College Fr. Chito Dimaranan, SDB, has publicly condemned the practice of overly unorthodox representations in a 2016 Facebook post. In the post he says, “Some of the statues that I see have nothing remotely related to the mystery of the Son of God becoming man, and assuming the humility and simplicity of a child in the Santo Niño image.”

He argues that “shallow popular religiosity needs to be purified” of superficiality and the “pagan culture of […] luck,” warning that Church leaders need to take action, else these santos add to the “misguided criticism that ‘Catholics’ practice idolatry.”

Lois maintains a similar stance. He says, “Some people […] do go overboard when dressing up their images [like] when Mary is made overly flamboyant [as if] she’s attending a masquerade. I even once saw a Santo Niño dressed as Mulawin. [It appears] sacrilegious,” advocating for “prudence when dressing up religious images.”

Further, Ofrasio explains that dressing saints in unorthodox ways “trivializes [religious figures] and loses what they stand for,” turning them into “Barbie dolls,” though it may not be a devotee’s intention. He remarks, “What can we do [if] these are simple people expressing their faith?” and advises proper catechesis.

On the topic of exuberant santos, Ofrasio cites a talk he gave to the Esculturas Religiosas en las Filipinas where he calls santos excessively decorated with jewelry, precious gems and metals, and gold-embroidered garbs as “nakakaiskandalo sa mahihirap (insensitive to the poor)” and counter to the humility of the saints. He adds that the show of wealth camarero owners may steal attention from the saints themselves.

Lois and Ofrasio recommend modest santos that stay true to biblical and historical depictions and iconography. Still, Lois concedes that though he may prefer simpler santos, other devotees may see the sacred more in the intricate and extravagant.

Further, Ofrasio acknowledges that creative liberties are acceptable, so long as they are respectful and preserve the religious figure’s essence. He cites the Blessed Virgin Mary in Filipiniana and Jesus Christ in barong as acceptable inculturations.

The essence so vital in the depiction of santos is captured in the concept of unción sagrada—the characteristic of a religious image to convey a sense of the sacred and inspire the viewer to contemplate the mysteries that it represents. Whether or not an image resonates holiness, however, depends largely on devotees themselves and their eye for the divine.